Overview

A Historic Relationship

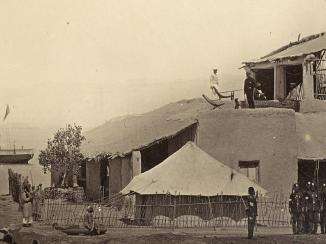

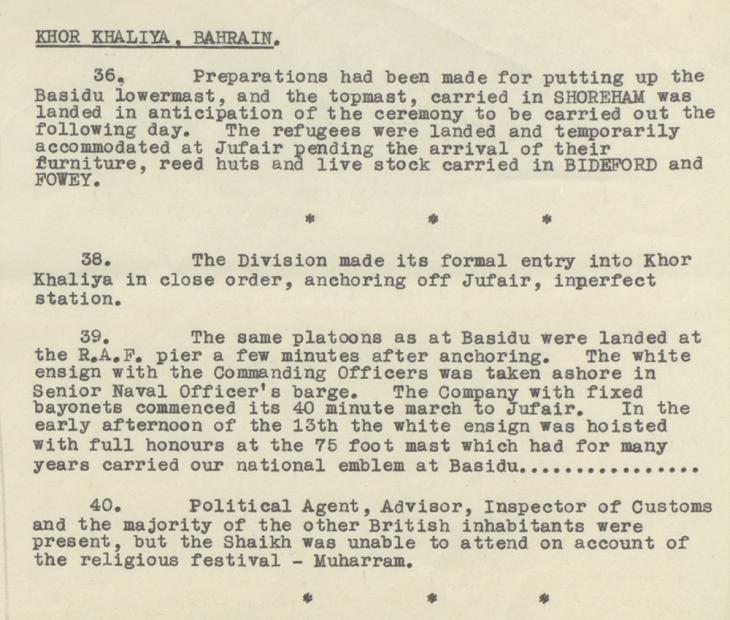

In 2018, British and Bahraini royalty formally opened HMS Jufair, a Royal Navy Support Station located in the Juffair district of Manama, Bahrain. History was repeating itself. In 1935 too, a Royal Navy station was opened on the same spot, transferred from the Iranian shore of the Gulf. The Navy’s White Ensign was hoisted over what was then Juffair village, in a ceremony attended by the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. and Charles Belgrave (the infamous Adviser to the Shaikh), as well as other British notables (Bahraini royalty, on this occasion, were unavailable).

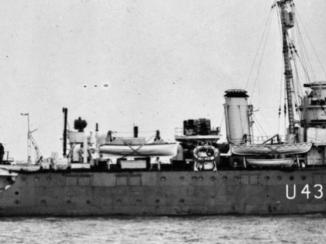

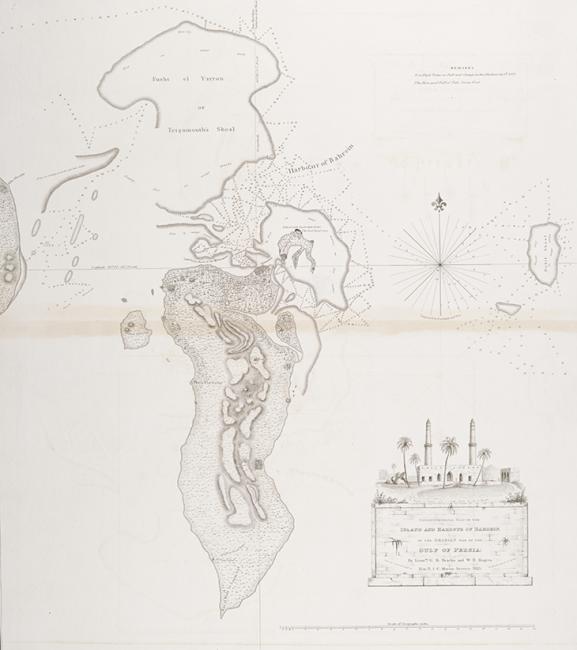

Juffair then became the last base of the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. Squadron, Britain’s permanent naval deployment in the Gulf. The Squadron was established following the 1819 campaign against “piracy”, when the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. had decided it was necessary to build on its victory over the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. and maintain a long-term military presence in the region. The Squadron was initially part of the East India Company’s Bombay Marine The navy of the East India Company. , which was disbanded in 1863. After a six-year absence, the Squadron was reformed in 1869, as a detachment of the Royal Navy, though with mainly Indian personnel. From then on, the commanding officer was known as the Senior Naval Officer, Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. (SNOPG).

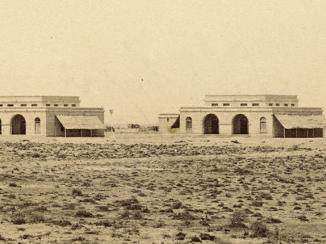

The Squadron’s first base was at Basaidu, on Qeshm Island off the coast of Iran in 1823. In 1913, though Basaidu was retained, the Squadron’s main base was moved to Hengam Island, which was thought to have a better climate and a more strategic location by the Straits of Hormuz. The base moved again in 1935 to Bahrain, as both Basaidu and Hengam were abandoned under pressure from the government of Reza Shah Pahlavi in Iran. The Squadron lasted, under different formations, until Britain’s withdrawal from the Gulf in 1971.

Policing the Gulf

Anglocentric historiography has credited Britain with bringing stability to the Gulf, through treaties such as the General Treaty with the Arab Tribes of the Persian Gulf (1820) and the Maritime Truce (1853). However, this belies the power dynamics imposed on the region. By excluding other European powers, and making local rulers dependent on British protection, Britain positioned itself as the ‘gendarme’ of the Gulf, and ensured its supremacy over the strategic sea lanes leading to India. The Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. Squadron provided the military clout behind the Political Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. , and the gunboats that underwrote the treaties.

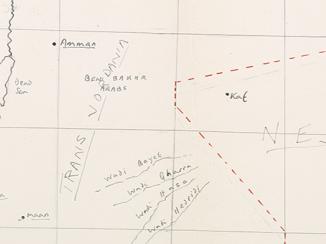

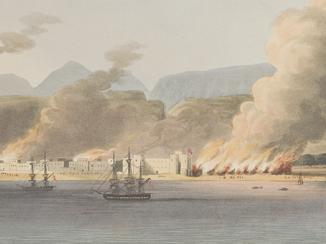

The Squadron undertook various duties. It combatted maritime warfare and attacks on shipping (“piracy”), which usually meant retroactively destroying ships, or imposing fines after an attack, sometimes as collective punishment on entire towns. It also detained and searched ships suspected of carrying enslaved people (who were brought to the Gulf from Africa), or firearms (which flowed from the Gulf to India’s restive Northwest Frontier). Further, it enforced British rules: nakhudas were obliged to carry British-approved documents and fly British-approved flags, while severe limits were imposed on the movements of local warships. Several times, as with Abu Dhabi in 1835, Bahrain in 1868, and Qatar in 1895, it destroyed local fleets, stymying the ability of local rulers to wage war or pursue independent policies at sea. On multiple occasions, it turned its guns on Iran to enforce wider imperial interests, including during the 1856-57 Anglo-Persian War. The Squadron also participated in subtler means of consolidating colonial control, such as producing detailed survey maps, and installing undersea telegraph lines connecting the Gulf to Britain and India.

Pax Britannica?

In 1922, Lord Curzon felt able to boast that ‘piracy has been supressed, slavery has been abolished, […] and order has been observed by the exertions of Great Britain’ (Mss Eur F112/278, f. 132r) – sentiments echoed in writings on Gulf history down to modern times. Despite such claims, neither “piracy” nor the trade in enslaved people was eradicated from the Gulf by British warships. The India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records show that both persisted as late as the 1940s. Over 120 years after the General Treaty, Britain’s “pacification” of the Gulf remained incomplete.

![A telegram from the Political Resident in the Persian Gulf to the Political Agent in Muscat describing the ‘continued presence [of] pirates’, 9 November 1941. IOR/R/15/6/419, f. 42r](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_r_15_6_419_0094.jpg?itok=lv1_JkGx)

The Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. Squadron should not, therefore, be seen as omnipotent. Its resources were always limited, with only two to four gunboats from 1869. Moreover, some of the Gulf’s more inaccessible waterways were resistant to colonial control, including the inland sea of Khawr al-Udayd and the Shihuh lands on the Musandam Peninsula. Local craft, meanwhile, were able to evade large British men-of-war, to the extent that in 1852 the Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Navy openly admitted that the trade in enslaved people was almost out of control.

![Excerpt of a letter from Captain H. J. Leeke, Commodore of the Indian Marine, to Lord Falkland, Governor of Bombay, describing the difficulties of ‘[suppressing] the slave trade’ in the Gulf, 7 October 1852. IOR/R/15/1/130, f. 284v](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_r_15_1_130_0599.jpg?itok=iw5L0Ny7)

Perhaps because of their limitations, appearances truly mattered to British forces in the Gulf. Following a 1901 visit by the Russian cruiser Varyag, which dwarfed anything fielded by the Squadron, British officials diverted the even larger HMS Amphitrite to the Gulf, in order to counteract ‘the deep impression [made] on the people’ (IOR/L/PS/20/C248B, p. 38).

Like all forms of colonial policing, the Squadron’s actions often constituted shows of force to project an image of invincible British power and to discourage any opposition to its imperial order. For example, when a crowd pelted a British officer with stones in Dubai Creek in 1855, the Senior Naval Officer took two warships to Dubai to demand an apology from the ruler, Shaikh Sa‘id bin Butti, for this ‘insult’ (IOR/R/15/1/149, f. 136v). Another more serious demonstration occurred in Bahrain in 1868. According to J. G. Lorimer’s Gazetteer, Shaikh Muhammad Al Khalifa’s attack on Qatar in that year was ‘regarded throughout the Gulf as a test of British preparedness to maintain peace at sea’. British warships subsequently destroyed Shaikh Muhammad’s fleet and fortress at Muharraq as an ‘exemplary punishment’ and assertion of British might in the region (IOR/L/PS/20/C91/1, p. 894).

Later, at a 1930 lecture at the Royal United Services Institute, Vice-Admiral Bertram Thesiger told an anecdote of supressing a 1928 rebellion in Sur against Britain’s protégé the ruler of Muscat, Sultan Taymur bin Faysal Al Bu Sa‘id. In language revealing of British imperial attitudes, Thesiger recounted bombarding a fort ‘to impress the inhabitants’ before bringing the local Shaikhs on board a gunboat to warn them that if they did not ‘behave’, they would see what Britain’s ‘big guns’ would do (Parry, p. 331).

Thus, the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. Squadron’s actions were often projections of British supremacy in the Gulf, while its actual effectiveness was less total than it was made out to be.

Towards a new historiography of British imperialism in the Gulf

Anglocentric historiography has depicted the British naval presence in the Gulf as both benevolent and all-powerful. It was neither. This is one of the principal myths in Britain's “historic relationship” with the Gulf, which was celebrated at the reopening of HMS Jufair. The power dynamics and violence that underpinned that relationship, and the myths that surround it, are recorded in and can be exposed by the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records.