Overview

A More Aggressive Approach

In December 1818, Captain Francis Erskine Loch arrived in the Gulf to serve as Britain’s Senior Naval Officer. In the years leading up to Loch’s appointment, reports of attacks on commercial shipping in the Gulf and Indian Ocean had been increasing. These attacks were blamed on the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. tribe operating out of Ra’s al-Khaymah. Britain had fought a military campaign against the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. in 1809 but had been unable to suppress the tribe, whom they referred to as “pirates”. Subsequently, the main strategy for dealing with Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. attacks had been to provide protection to convoys of trading vessels. However, Loch now opted for a more aggressive approach, seeking out and attacking vessels belonging to the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. wherever he could find them.

![A depiction of the attack on Linga [Bandar-e Lengeh] during the military campaign of 1809. Public domain. Image digitised by BLQFP from Richard Temple, Views in the Persian Gulph (London: W. Haines, 1813)](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/temple_5_-_body_image.jpg?itok=CE6vvGzA)

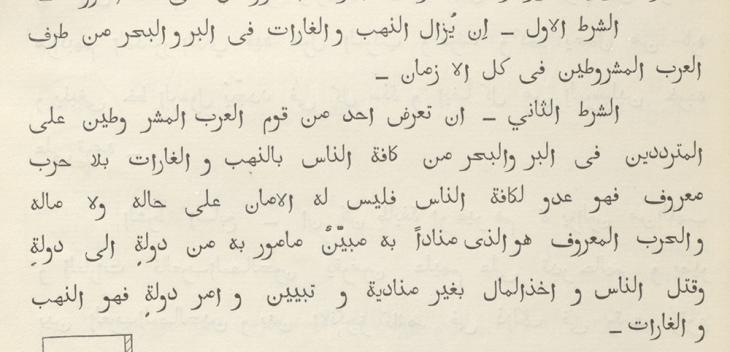

The India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records provide evidence of the vigour with which Loch pursued his task. For example, on 28 December 1818, he encountered four ships ‘belonging to the Joasmees [ Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. ], having three prizes in tow’ (IOR/F/4/649/17852, f. 221v). He pursued them and captured two of the ships, along with ten crew members who were interrogated and then sent to Bombay as prisoners. Transcripts of these interrogations offer an insight into the Qawasim’s activities. In their answers, the prisoners describe an operation that involved several Arab tribes, who were carrying out raids across the Indian Ocean as far as Sind and Gujarat, bringing plunder and prisoners back to the Gulf. These and other reports suggest that what the British defined as piracy actually stemmed from a number of conflicts, based on a range of shifting alliances in the Gulf and beyond. Nevertheless Loch was convinced that there was a single piratical operation led by the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. , and therefore instructed an officer under his command to ‘do your utmost in destroying all Joasmee vessels you may fall in with provided you cannot capture them’ (ff. 334r-334v).

![A list of ‘Joasmee’ prisoners of war captured by HMS Eden, 29 December 1818. The ‘Country’ column records all of the prisoners as being from ‘Yaman’ [Yemen], which is at odds with Loch’s assertion that they were Qawasim. IOR/F/4/649/17852, f. 322r](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_f_4_649_0648.jpg?itok=RVy2hxjK)

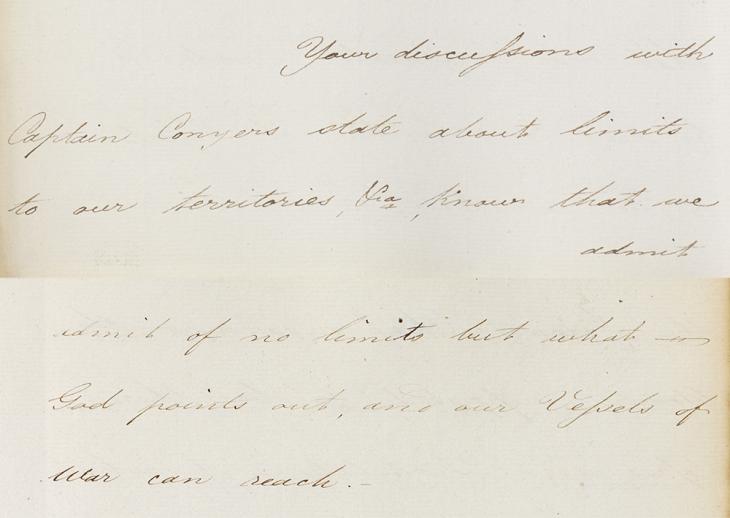

For Loch, piracy had to be confronted, and no compromise was possible. In March 1819, he received a communication from Shaikh Hasan bin Rahma al-Qasimi, the ruler of Ra’s al-Khaymah, who suggested a truce whereby British vessels, as well as the coastlines connected with British territories in India, would be left alone by the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. . Loch, however, rejected this, asserting in his reply that ‘we admit of no limits but what God points out, and our vessels of war can reach.’

This reveals something of Loch’s motivation and worldview: he believed in an absolute “right” for British ships, and those of British subjects, to navigate freely in the waters of the Gulf and the Indian Ocean. Further, this “right” ought to be protected and upheld, by force if necessary. He consequently refused to negotiate with the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. , and supported calls for a military expedition to complete the task, as he saw it, of “pacifying” the Gulf.

The 1819 Expedition

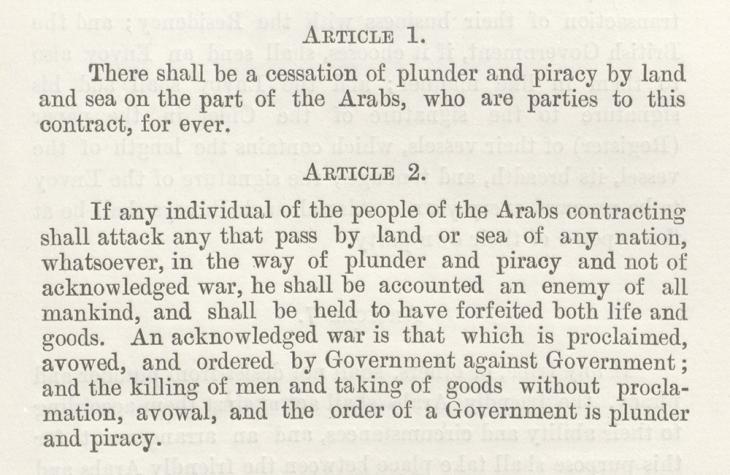

This expedition took place in December 1819. British forces rapidly overwhelmed Ra’s al-Khaymah, and the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. and other nearby tribes signed a treaty agreeing to ‘a cessation of plunder and piracy’. According to Major General Sir William Grant Keir (later known as Sir William Keir Grant), who led the expedition, this treaty was ‘calculated to produce the suppression of piracy, and the establishment of a free and secure commercial intercourse between the different ports in the Gulf and those of India’ (IOR/F/4/651/17855, f. 72r).

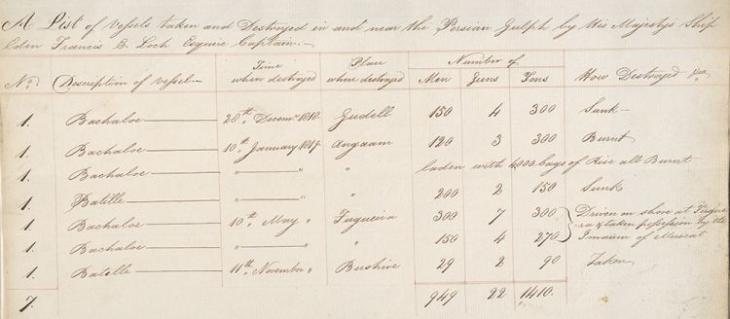

The expedition, however, was not yet over. Loch continued to seek out the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. and their allies elsewhere in the Gulf, even carrying out attacks on ships in the ports of Asaluyeh and Kangan on the Persian coast. The accusations against these ships turned out to be unfounded, and Britain eventually had to pay compensation. Nevertheless, the expedition had successfully imposed a new order in the Gulf that Britain would oversee for the next 150 years.

![Loch's report of his attacks on ‘pirate vessels’ at Assaloo [Asaluyeh] and Coongoon [Kangan], in a letter to J. A. Collier, 26 January 1820. IOR/F/4/651/17855, f. 121v](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_f_4_651_0247_0.jpg?itok=ygGd2V8o)

Enduring Controversy

Over one hundred years after he left the Gulf, Loch remains at the centre of a debate over the 1819 expedition. In 1966, Charles Belgrave published his book, The Pirate Coast. Belgrave had worked as Advisor to the rulers of Bahrain for thirty years, before popular pressure forced him from this position in 1957. In his subsequent writings, he sought to defend the British record in the Gulf. The Pirate Coast provides an account of the 1819 expedition, with Loch’s unpublished diary (now part of the National Records of Scotland) as its main source. ‘Loch’s diary’, Belgrave asserts, ‘makes the reader realise how many British lives were sacrificed in suppressing piracy.’ Furthermore, he argues, this was done ‘not with any ambitions towards territorial conquests, but in order to make the seas safe for the ships of all nations’ (p. 192).

In contrast, Loch comes in for particular censure in Sultan Muhammad al-Qasimi’s 1986 monograph, The Myth of Arab Piracy in the Gulf. Al-Qasimi argues that Arab piracy was a ‘myth’ promoted by Britain in order to conceal its imperialist ambitions. He describes Loch as ‘one of the most reckless naval officers in the Gulf’ (p. xvi), and his actions during the 1819 expedition as ‘an orgy of destruction of Arab ships on both sides of the Gulf’ (p. 225). According to al-Qasimi, Loch’s indiscriminate attacks on Arab shipping themselves constituted acts of piracy.

Loch therefore remains a controversial figure, and in many ways has come to represent the larger debate surrounding Britain’s presence in the Gulf. For some, he was a brave and principled naval officer, acting decisively to bring order and peace to an allegedly chaotic and dangerous region. For others, he embodies the hubris and aggression which underpinned a century and a half of British dominance in the region.

Loch’s Legacy

Either way, Loch certainly contributed to the framing of an attitude towards the Gulf that endures to the present day. In July 2019, British Royal Marines seized a tanker off Gibraltar containing Iranian oil, and a few weeks later the Iranian military detained a British-flagged tanker in the Gulf in retaliation. The UK Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt described the Iranian response as ‘an act of state piracy’, and ‘a flagrant breach of the principle of free navigation on which the global trading system and world economy ultimately depend.’ The tanker in question was released two months later, but Britain’s Royal Navy has subsequently maintained a heightened military presence in the Gulf. Hunt’s words are striking in their similarity to the language used two hundred years earlier. It is a reminder of the significance of the 1819 expedition, and how the principles asserted then are still being used to justify Western intervention in the Gulf region today.

The letters and reports produced by Loch are among the many records available on the QDL that document the 1819 expedition. Together they provide an opportunity to revisit this important event and examine how it has shaped the modern history of the Gulf.