Overview

For over a century, starting from 1820, the bases that facilitated Britain’s coercive naval power in the Gulf squatted on Basaidu and Hengam, Iranian territory whose sovereignty was never ceded. These bases smoothed the progress of colonial wars, including against Iran itself. After taking the Iranian throne in 1925, Reza Shah Pahlavi sought to assert control over Iran’s southern coast, end colonial encroachment in Iran, and set Anglo-Persian relations on a more equal footing. In so doing, his government mounted a serious challenge to British dominance in the Gulf.

At this time, British officials were forced to countenance the irregular status of their naval bases. As J. G. Laithwaite noted in 1934 while working for the Indian Office, the British position was ‘legally extremely weak and in practice subject to a continual challenge from Persia of a rather embarrassing nature’ (IOR/L/PS/12/3840, f. 540r). Foreseeing the loss of Basaidu and Hengam, British officials began scouting for a new base in the region, and turned naturally to their client-ally, the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman.

The Musandam Option

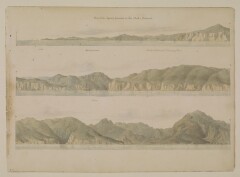

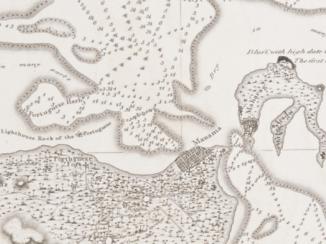

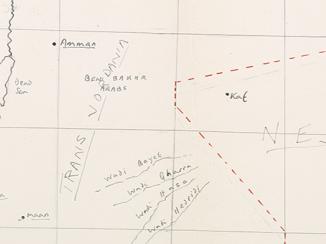

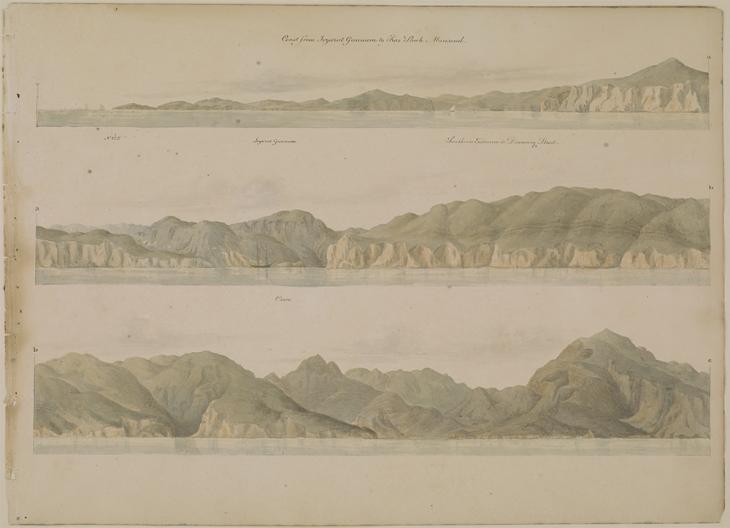

British imperial strategists had long eyed the Musandam Peninsula, across the Straits of Hormuz from Hengam. In 1927, the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. Lionel Haworth argued for purchasing this region from the Sultan of Muscat, and turning it into a ‘Gibraltar at the head of the Gulf’ (IOR/L/PS/12/3840, f. 567r). He envisaged Musandam as a base securing British control of the sea-lanes leading in and out of the Gulf, just as Gibraltar was in the western Mediterranean.

Under pressure from Reza Shah, the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. again looked to Musandam, deeming the strait of Khawr al-Qawi (usually rendered Khor Kuwai or Quwai in British sources), at the tip of the Peninsula, to be an ideal location for a future base. Laithwaite describes the situation there as ‘admirable; there is deep water; we should be free from interference by Persia, and we should command the head of the Gulf’ (IOR/L/PS/12/3840, f. 568r). A combination of practicalities and inter-imperial rivalries, however, would thwart this project.

The French Connection

The international constraints on Britain in Musandam can be traced back to the nineteenth century, and to Zanzibar. In 1862, Britain and France had signed an agreement to guarantee the independence of the Sultanates of Muscat and Zanzibar. This followed years of mutual suspicion between British and French colonists in the Indian Ocean, which came to a head when a large French missionary station was established in Zanzibar in 1860. Hawkish British officials feared that this could become a military stronghold and facilitate French conquest of the island. This would not have been without precedent: missionaries had earlier provided pretexts for French intervention in Tahiti and Indochina. The 1862 agreement was concluded between London and Paris to avert this colonial rivalry.

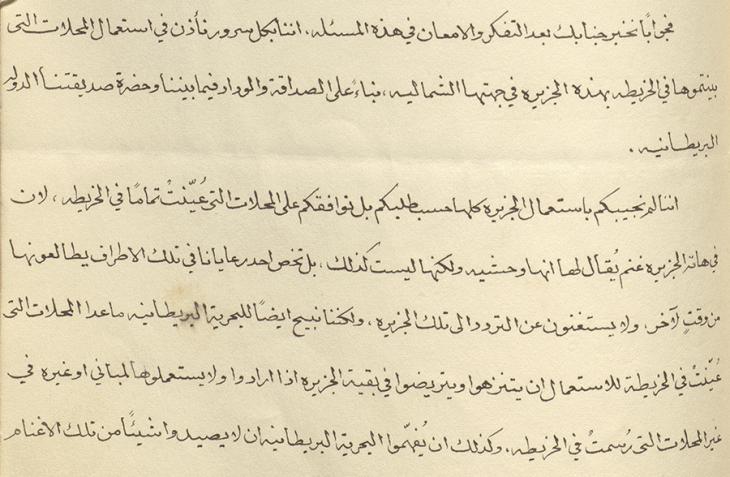

This agreement had long-range consequences in the Gulf. It may have spared Muscat from a still deeper degree of British imperial incursion: its provisions prevented the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. from making Muscat a formal protectorate in 1890, and from taking control of the Sultanate’s customs in 1898. Britain had gone to some lengths to try to buy the French out of Muscat, and to acquire a “free hand” in the country, offering large tracts of colonised territory in Gambia and Sudan in return, yet Paris was unmoved.

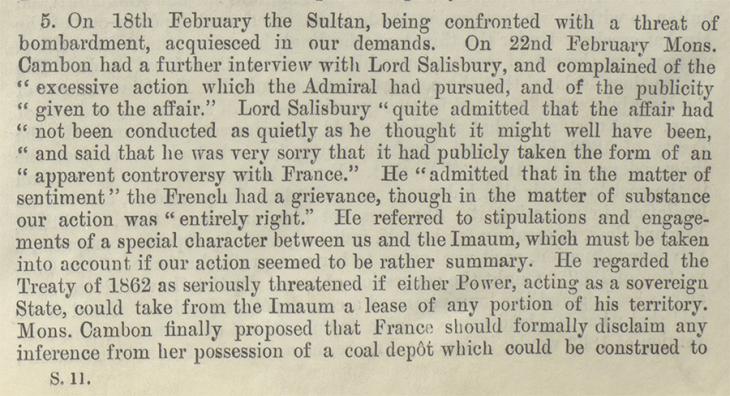

On the other hand, Britain was quick to use the agreement to prevent French inroads into the region. In 1898, France obtained a concession from the Sultan for a coaling station in Muscat. Alarmed at this incursion into what it viewed as its exclusive sphere of influence, Britain protested (threatening the Sultan with bombardment in the process).

The Foreign Office used the 1862 agreement to compel French officials to compromise. France acquiesced, agreeing that its coaling station would have no fortifications, flags, or sovereign rights over the land. In the 1930s, this precedent meant that the proposed base in the Khawr al-Qawi was guaranteed to meet with French protests, and possible demands for their own naval base.

These diplomatic constraints, along with practical concerns from both India and the Admiralty about the expense and hardship of running a base on remote Musandam, meant that ‘Gibraltar at the head of the Gulf’ never materialised.

The Transfer

When Basaidu and Hengam were abandoned over a few days in April 1935, Britain’s main base in the region was transferred to Juffair, Bahrain. Ever anxious not to appear weak before colonised populations, British authorities instructed the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. to ‘spread appropriate rumours on the Arab shore’ and craft a communique presenting the withdrawal as a British initiative, and not the result of Iranian pressure, in order to minimise the loss of any ‘prestige’ (IOR/L/PS/12/3840, ff. 362r, 340r).

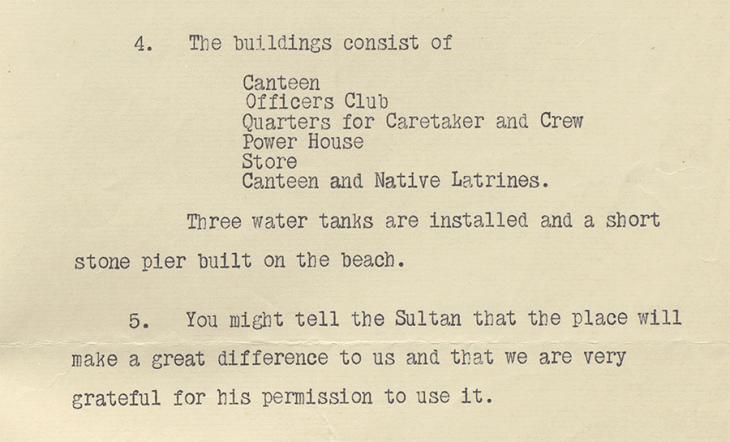

The Khawr al-Qawi meanwhile became a small, subsidiary base. Only a canteen, officers’ clubhouse, and basic amenities, without fortifications or flags, were built on the island of Jazirat Umm al-Ghanam (sometimes called ‘Sheep Island’ or ‘Goat Island’ in English).

The Khawr al-Qawi from the Second World War to the Present

The base was reinforced during the Second World War, housing a telegraph station and used by the RAF as an air-sea rescue base. Judged no longer useful in the Cold War, the facilities on Jazirat Umm al-Ghanam were handed over to the Sultanate in September 1956. The handover was unpublicised, again for fear of losing ‘prestige’ during a time of great tension in the wider region; it took place weeks after the nationalisation of the Suez Canal by Egyptian President Gamal Abd al-Nasser, and just before the subsequent Tripartite attack on Egypt. That left Juffair as the only British base in the Gulf. Britain abandoned Juffair in 1971, before the United States took over in 1972. The Royal Navy returned to the base in 2018.

Now operated by the Royal Navy of Oman, the site at Jazirat Umm al-Ghanam featured in the British media after it was visited by royalty in 2019, with coverage focusing on confrontation with Iran, as well as Britain’s defence of shipping lanes and the Arab Gulf monarchies. Evidently, the history of tensions goes on.