Overview

For over thirty years, Charles Belgrave was an immensely powerful figure in Bahrain who played an instrumental role in its development. Between 1926 and 1957, he served as Adviser to the rulers of Bahrain, Sheikh Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa (r. 1923–42) and Sheikh Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa (r. 1942–61).

Belgrave was born in England on 9 December 1894 and educated at Oxford University. After graduating, he joined the British Army and, during WWI, served in Egypt, Sudan and Palestine with the Imperial Camel Corps Brigade. After the war, he became an administrative officer in the British League of Nations mandate of Tanganyika Territory (formerly German East Africa).

‘Good Salary and Prospects to [a] Suitable Man’

In the summer of 1925, while on leave in London, Belgrave read an advertisement for a vacancy in The Times newspaper that was to transform his life.

Young Gentleman, aged 22/28, Public School and/or University education, required for service in an Eastern State. Good salary and prospects to suitable man, who must be physically fit: highest references; proficiency in languages an advantage.

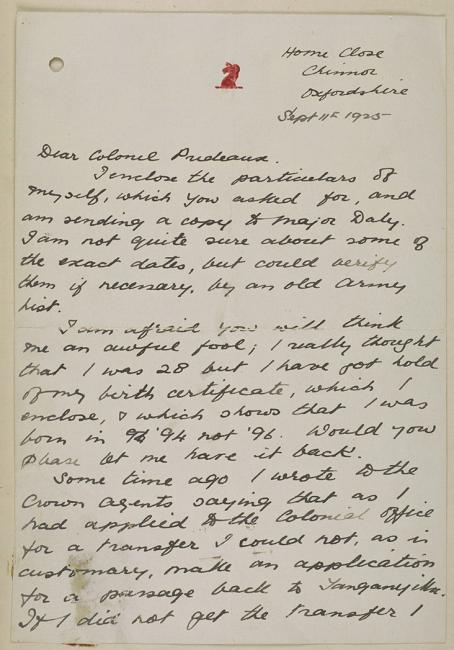

Belgrave applied for the post and was interviewed by British Government officials, after which he was offered the position of Adviser to Shaikh Hamad. A letter Belgrave wrote to Prideaux in September 1925 reveals that he had conveniently forgotten his own age when he applied: he was thirty-one and the upper age limit for applicants was twenty-eight.

Before setting out for Bahrain, Belgrave completed an Arabic course at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London and married his fiancée, Marjorie Lepel Barrett-Lennard.

Tensions and Colonial Aims

Belgrave began his new role in April 1926 at a tense time in the country; Shaikh Hamad had been installed as ruler by the British three years earlier when his father Shaikh Isa bin Ali Al Khalifa was forced to step down. Lingering tensions remained between Shaikh Hamad and factions within Bahrain – including members of his own family – that supported his elderly father, Isa.

Though Bahrain was nominally independent, Britain had dictated its foreign policy since the nineteenth century. In 1900, its power over the islands was consolidated with the creation of the post of British Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain. Although Belgrave was an employee of the Shaikh, as his hiring process clearly demonstrates, his position was closely tied to the colonial aims of the British in the region. Belgrave swiftly became a powerful figure in Bahrain and came to be known simply as ‘The Adviser’.

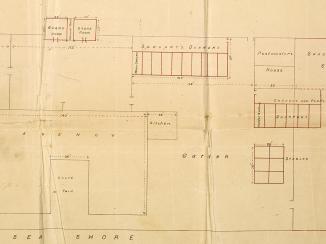

He ran Bahrain’s government, was the head of its police force and – in the absence of an organised legal code – personally operated its courts. Belgrave oversaw a programme of modernisation that included the creation of an education system, a police force, a health service and an extensive series of public works. During this transitional period, power became centralised, leading to a further consolidation of the British and Al Khalifa family’s positions. Belgrave was also instrumental in supporting oil exploration in the country, which was the first in the region to discover oil, in 1932.

‘A Society of Self-Satisfied Czars’

It is clear from the frequency with which Belgrave’s name occurs in the records of the Political Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. that his role encompassed a range of matters, and that he had an acute attention to detail.

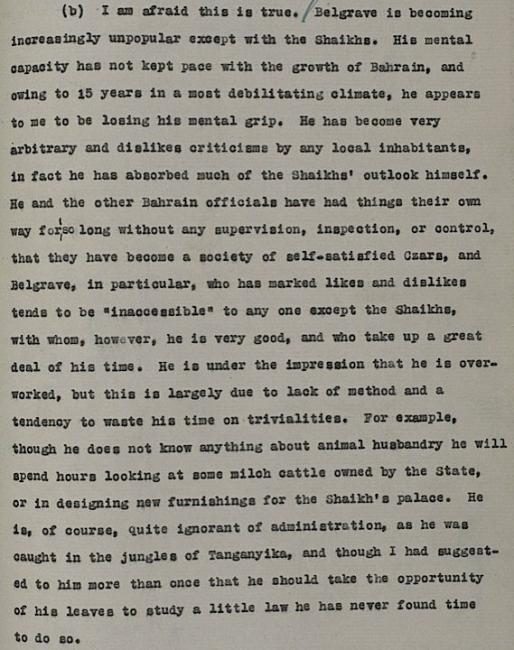

In fact, Belgrave’s fastidiousness was criticised. In May 1941, Charles Geoffrey Prior, the British Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , wrote to his superiors in India that Belgrave had a ‘tendency to waste time on trivialities’. In the same letter, Prior also claimed that Belgrave’s increasing aloofness had caused a drop in his popularity and that he ‘and the other Bahrain officials have had their way for so long […] that they have become a society of self-satisfied Czars’.

Prior’s concern was prescient. By the 1950s, many Bahrainis had grown angry at the amount of power he held. Belgrave had come to embody British Imperialism in the Middle East at a time of fervent Arab nationalism and when, after the Suez Crisis, Britain’s standing in the region had reached a nadir. Belgrave was viewed by many as an impediment to the transition to democracy.

Eventually, in April 1957, Belgrave was forced to leave and was never to set foot in Bahrain again. Once back in Britain, Belgrave wrote an autobiography named Personal Column, which offers an insight into his life and the development of Bahrain. In the book’s conclusion, Belgrave states that if a more liberal system of government were to be introduced in Bahrain, it should be done gradually and that any attempt to ‘rush the process’ would be ‘disastrous’ – a clear expression of the attitude that eventually made his position in the country untenable and forced him to leave. Belgrave’s legacy in Bahrain remains a contentious issue, but it is one that anyone wishing to understand the modern history of Bahrain cannot help but engage with.