Overview

On 29 August 1933, the acting Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , Percy Gordon Loch, received a letter from the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. at Kuwait, Lieutenant-Colonel Harold Dickson, informing him of rumours circulating in Kuwait that a Persian naval officer had hauled down the British flag at Basaidu, the base of the British Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. Naval Squadron.

A swift response

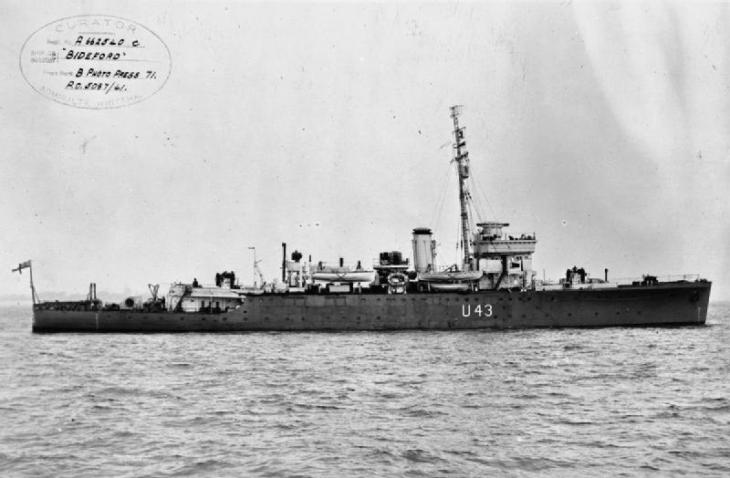

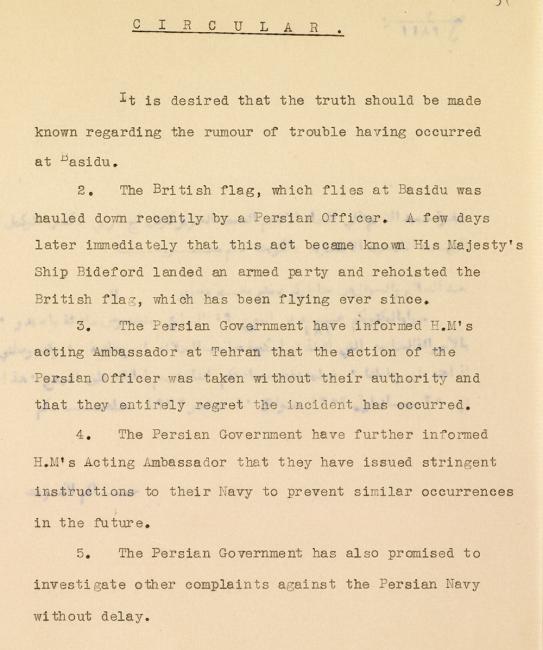

The British response was immediate and decisive. On 7 September 1933, Loch sent a circular telegram – addressed to the Senior Naval Officer in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , as well as the British political agents at Bahrain, Kuwait, and Muscat – confirming that a British flag had been pulled down by a Persian officer, but that only a few days later, as soon as it had been made aware of the incident, the HMS Bideford had landed an armed party at Basaidu and the flag had been rehoisted. Loch’s telegram further stated that the Persian Government had informed His Majesty’s Chargé d'Affaires that the officer had acted entirely without authority, and that it had issued strict instructions to the Imperial Iranian Navy (IIN) to prevent any such occurrences in the future.

In a second circular telegram, issued on the same day, Loch requested that his previous message be translated into Arabic and distributed to the rulers of the Arabian coast, ‘who should be requested to give copies to all their notables, and by all other possible means to make it public’ (IOR/R/15/5/173, f. 47r). Loch concluded his telegram with a point for the political agents’ personal information only: the Royal Navy’s First Destroyer Flotilla was expected to arrive at the Island of Henjam (Hengam) on 15 September, for the purpose of displaying the British flag along the Arabian coast of the Gulf. An amended version of the message intended for circulation was issued on 8 September. In his subsequent correspondence with Dickson, Loch stressed that care should be taken to avoid linking the arrival of the Royal Navy flotilla with the incident at Basaidu, and likewise to avoid any suggestion of it presenting a threat to Persia.

An immediate impact

The fact that the swiftly announced flotilla tour was a direct response by British officials to the Basaidu incident was tacitly acknowledged in a telegram from Dickson to Loch, dated 19 September 1933, which reported that the circular, followed by news of the flotilla, had had the ‘best possible effect’ on public opinion in Kuwait (IOR/R/15/5/173, f. 62r). The flotilla, consisting of a flotilla leader, HMS Duncan, and eight destroyers from the British Mediterranean Fleet, spent nearly a month in the Gulf, calling at Basaidu, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar along the way.

The Durbar: echoes of 1903

It was at Dubai, on 23 September 1933, where the rulers of the Trucial States A name used by Britain from the nineteenth century to 1971 to refer to the present-day United Arab Emirates. were invited to a durbar A public or private audience held by a high-ranking British colonial representative (e.g. Viceroy, Governor-General, or member of the British royal family). , that the purpose of the flotilla’s tour was made very clear. In his address, Loch – alluding to a statement made at a previous durbar A public or private audience held by a high-ranking British colonial representative (e.g. Viceroy, Governor-General, or member of the British royal family). by George Curzon, during his tour of the Gulf as the Viceroy of India almost exactly thirty years earlier – told the rulers that the British Navy’s intervention in the Gulf had ‘compelled peace and created order on the [s]eas’, and had saved them from extinction at the hands of their enemies (IOR/R/15/5/173, f. 69r). He also reminded his audience that the various treaties agreed between the British Government and the rulers of the south-eastern coast of Arabia (beginning with the General Treaty with the Arab Tribes of the Persian Gulf An agreement made in 1820 between Britain and ten tribal rulers of the eastern Arabian coast, often seen as marking the start of 150 years of British hegemony in the region. of 1820) had made Britain the overlord and protector of the Trucial States A name used by Britain from the nineteenth century to 1971 to refer to the present-day United Arab Emirates. .

Disagreement over the durbar

Loch’s durbar A public or private audience held by a high-ranking British colonial representative (e.g. Viceroy, Governor-General, or member of the British royal family). , which he had initially proposed in a telegram on 12 September 1933, had led to some difference of opinion between senior officials at the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. and the Foreign Office, with the latter questioning the wisdom of inviting comparisons between a durbar A public or private audience held by a high-ranking British colonial representative (e.g. Viceroy, Governor-General, or member of the British royal family). given by a Viceroy and one given by an acting Resident. Nevertheless, the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. was strongly in favour of proceeding, and an agreement was reached following some revision of Loch’s proposed address to the Trucial shaikhs, to avoid repeating the words of Curzon’s original speech.

Confidence restored, or supremacy reasserted?

Thirty years on from Curzon’s durbar A public or private audience held by a high-ranking British colonial representative (e.g. Viceroy, Governor-General, or member of the British royal family). , the British had taken a relatively minor act of dissent at Basaidu as an opportunity to make a very public display of their naval dominance in the Gulf. It was thus made clear to the Arab rulers that the British Government would not tolerate even the slightest affront to its reputation. Loch’s remarks at Dubai were intended to remind the Trucial shaikhs of their relationship with the British Government and their treaty obligations, as he warned them that ‘[t]hese engagements are binding on every one of you’ (IOR/R/15/5/173, f. 70r). In an express letter to the Government of India’s Foreign Department, dated 19 October 1933, Loch concluded that confidence in the British had returned following the sight of the flotilla and the landing of an armed party at Basaidu, ‘and will remain so just so long as we show ourselves determined’ (IOR/L/PS/12/3775, f. 17r).