Overview

Pirates or Merchants?

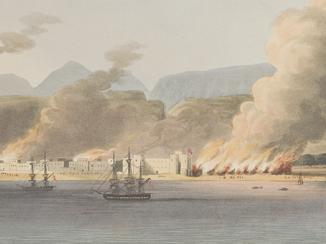

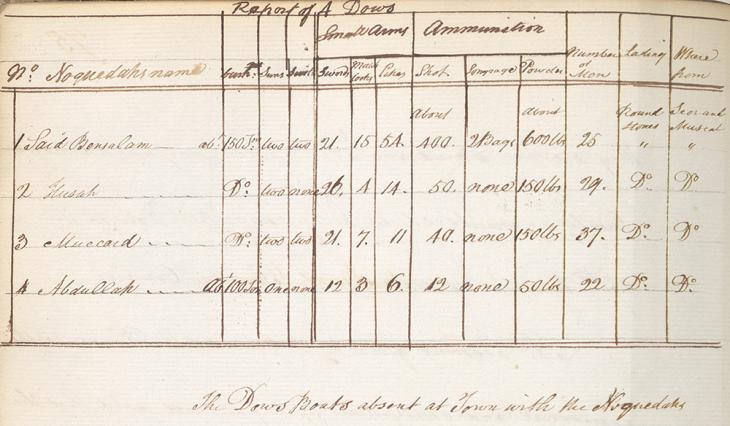

For a number of years, East India Company ships in the Indian Ocean had been subject to attacks at sea, often carried out by vessels manned by Arab crews from the Gulf. Identifying the antagonists, however, was not a simple matter. For example, on 22 November 1808, the Company ship Lively encountered four Arab vessels off the northwest coast of India, near Mangrol, and there was an exchange of fire. Later, the ships in question arrived at the port of Surat, where they were detained and inspected. A report, compiled by Lieutenants John Hall and James Watkins, listed the arms and ammunition on board each vessel, presenting this as evidence that they had been sailing with aggressive intent. However, Captain Robert Budden, the Commodore of Surat Station, was unconvinced, declaring ‘it is impossible to say whether they were on a piratical or mercantile expedition, perhaps both’ (IOR/F/4/288/6503, f. 104r).

This comment encapsulates the difficulty faced by those seeking to address the problem of “piracy” in the Indian Ocean: the traffic on the seas could not be neatly divided into “pirates” and merchants. Moreover, ships of all colours, including the British, had shown themselves willing to deploy force to gain an advantage over their rivals. As a result, the British response to piracy had been piecemeal, confronting individual aggressors when and where they could be found.

The spread of Wahhabism

This began to change as the problem of piracy became associated with another perceived threat to British interests: the rise of the Emirate of Dirʿiyyah, the first Saudi state. Following its foundation in 1744, the emirate had expanded across the Arabian Peninsula, reaching as far as the Gulf coast to include a number of tribes there, most notably the Qawāsim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. or al-Qāsimī One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. tribe, based in Ra’s al-Khaymah.

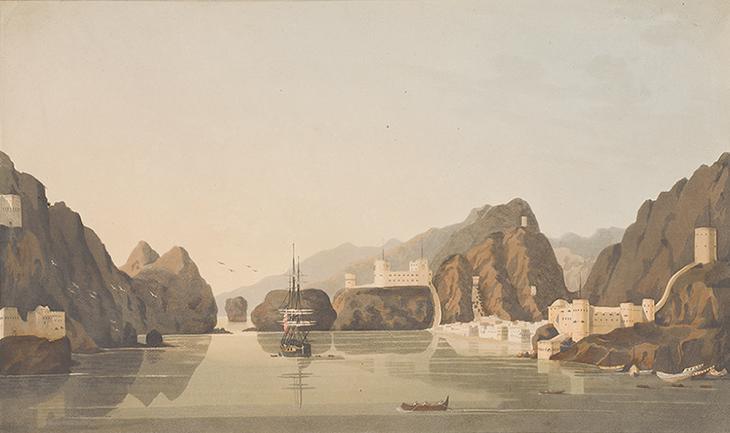

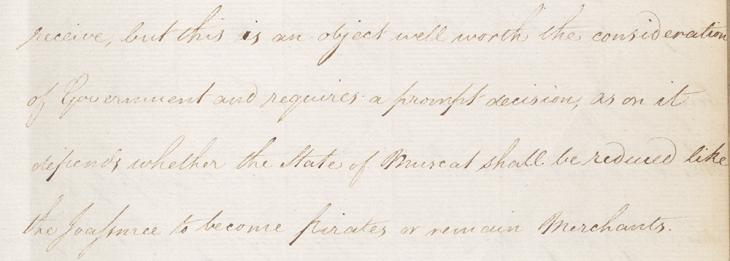

In 1808 Captain David Seton, the British Resident at Muscat, had returned to his post after a two-year absence and was alarmed by the growing influence of the new Saudi state and its version of Islam, known as Wahhabism. In a series of anxious reports, Seton highlights the danger presented by the Wahhabi movement, describing it as ‘a system of piracy that threatens to extend itself through all Arabia’ (f. 122r). The Wahhabis, Seton claims, were pressuring Arab merchants to carry out attacks on shipping in the Gulf and beyond. In response, the Imam of Muscat had asked Britain for help in defending his territories. Seton insists that this request is ‘well worth the consideration of Government and requires a prompt decision, as on it depends whether the state of Muscat shall be reduced like the Joassmee [ Qawāsim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. ] to become pirates or remain merchants’.

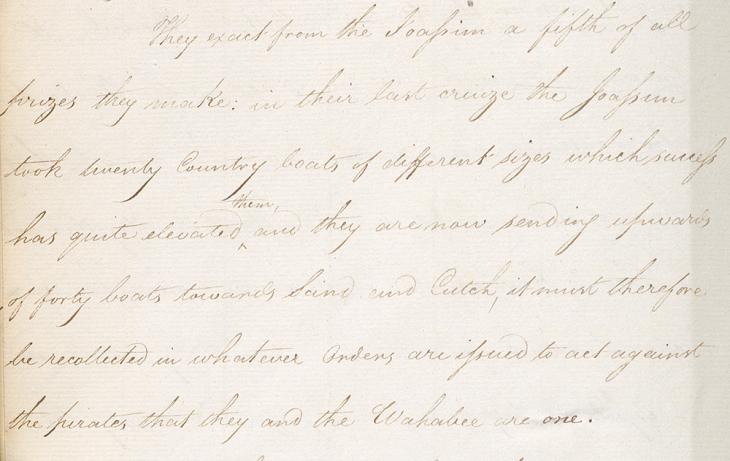

Whereas piracy and trade had previously been perceived as overlapping enterprises, Seton here presents them as opposites. Piracy was no longer to be seen as the activity of individual vessels seeking to gain commercial advantage, but instead as the conscious strategy of a relentlessly expanding Saudi state in its drive to spread Wahhabism. As Seton puts it, ‘it must therefore be recollected in whatever orders are issued to act against the pirates that they and the Wahabee [sic] are one’.

Intelligence from Arabia

In addition to the plea sent by the Imam of Muscat, Bombay received an appeal from the Governor of Mocha, where the East India Company had a factory An East India Company trading post. . The Governor claimed that, from a base in the port of Hudaydah, the Wahhabis were able to ‘exercise tyranny over the travellers by sea and commit depredations on those repairing to the port of Mocha’ (f. 137v). The port was consequently in decline, and the Governor requested British assistance to restore its security and prosperity.

With his letter, the Governor included a report by a local merchant, Ibrahim Purkar. Having recently returned from a pilgrimage to Mecca, Purkar describes his experiences of the hostility he and other pilgrims had faced in Saudi-controlled territories, and relays additional reports of the violence that had accompanied Saudi expansion. He concludes his account ominously, indicating that the Wahhabis’ intentions ‘are directed against India’.

![Extract from a translated memoir by Mohammed Ibrahim Purkar, calling on ‘the Almighty [to] disappoint them [the Wahhabis] and render their designs abortive’, 28 September 1808. IOR/F/4/288/6503, f. 136v](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_f_4_288_6503_0144.jpg?itok=X9QDDuCS)

Purkar’s account combines his first-hand experiences with local intelligence and hearsay about Saudi excesses, thus lending strength and urgency to the Governor of Mocha’s plea for a British intervention. In this way, his account tapped into the anxiety evident in British reports on the spread of Wahhabism.

A ‘more general and active’ policy

Although the East India Company knew little about the Saudi state or Wahhabi beliefs, what information was obtained only added to their fears. This in turn led to a shift in how piracy was discussed: the term was no longer used to describe specific attacks on British shipping, but rather to denote a larger operation, specifically identified with the Qawāsim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. . If this was left unchecked, Seton argues, ‘the trade of the Gulph [sic] and Red Sea must be annihilated, and that on the Malabar Coast subject to constant depredation from a desperate and fanatic enemy’ (f. 122v).

Faced with a growing volume of reports highlighting the threat posed by the Qawāsim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. “pirates”, the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. declared in June 1809 that there was now a need for ‘a more general and active course of measures for the repression of their atrocities’ (f. 68v). These measures would become the basis for Britain’s political and military presence in the Gulf for the next 150 years.