Overview

‘Disgraceful in the eyes of every civilised nation’

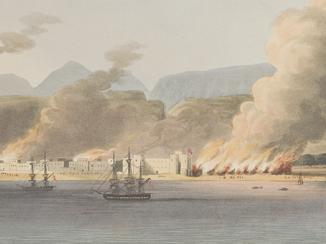

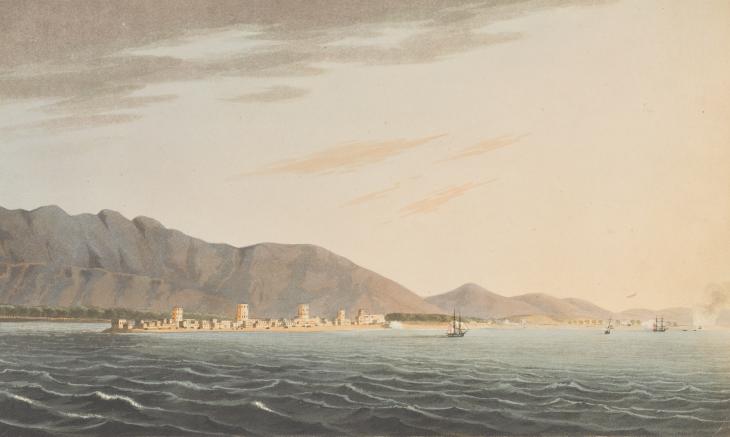

In 1819, Britain sent a military expedition out from Bombay [Mumbai] with the purpose of ‘destroying the maritime force of the Joassmees [Qasimis, i.e. Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. ] and other piratical tribes inhabiting the coasts of the Persian Gulph’. The expedition was to focus its efforts on Ra’s al-Khaymah, said to be the ‘chief seat of the piratical force’ (IOR/F/4/650/17853 ff. 7v, 19r).

In the preceding years, there had been a growing number of reports of attacks on shipping carried out by the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. . In their correspondence, the British repeatedly refer to the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. and their allies as ‘pirates’. The term conveys British feelings about the Qawasim’s activities, which were, in the words of the Governor of Bombay, Sir Evan Nepean, ‘disgraceful in the eyes of every civilised nation in the world’ (IOR/F/4/649/17852, f. 228r). In launching their military expedition, the British saw themselves as acting not merely to subdue a rival power, but to overcome a deeper, malign influence in the Gulf: that of piracy.

Britain achieved a rapid victory against Ra’s al-Khaymah, but this was just the start of their intervention. In early 1820, William Grant Keir, the leader of the expedition, concluded a treaty with the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. and their neighbouring tribes. Writing about this treaty, he asserted that it was ‘calculated to produce the suppression of piracy, and the establishment of a free and secure commercial intercourse between the different ports in the Gulf and those of India’ (IOR/F/4/651/17855, f. 72r). However, as Britain sought to implement this treaty, piracy proved to be an elusive and slippery concept.

‘A cessation of plunder and piracy’

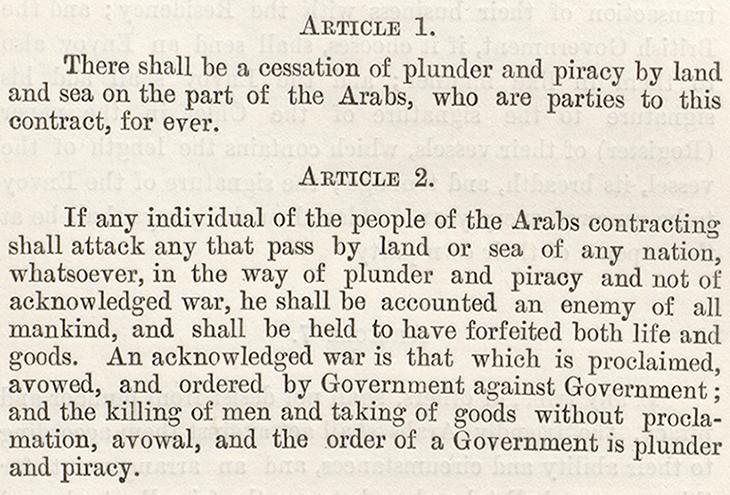

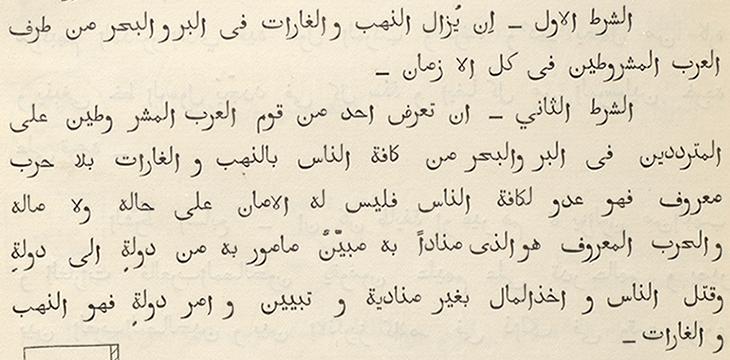

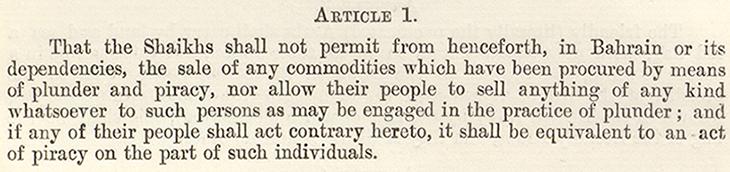

The text of the General Treaty with the Arab Tribes of the Persian Gulf An agreement made in 1820 between Britain and ten tribal rulers of the eastern Arabian coast, often seen as marking the start of 150 years of British hegemony in the region. , as it was titled, commits its signatories to ‘a cessation of plunder and piracy by land and sea on the part of the Arabs, who are parties to this contract, for ever.’ The second article attempts to define piracy by drawing a distinction between it and acts of ‘acknowledged war’.

This distinction was intended to show that Britain did not seek to become involved in the wider political affairs of the Arabian Peninsula. As a dispatch from the Supreme Government of India explicitly states, ‘we are anxious to avoid all interference in the concerns of the Arab states beyond what may be necessary for effecting the suppression of piracy’ (IOR/F/4/650/17854, f. 386v).

Arab perspectives

In practice, however, such a distinction was difficult to maintain. In that period, Arab tribes in the Gulf were vying for power and resources. Raids – by both land and sea – were customary between peoples with no established relations, especially those who were commercially active (Al-‘Aqqad, pp. 68-9). Such raids had recently intensified due to the rise of Wahhabism, which was seeking to unite the Arab tribes under a strict interpretation of Islam, by force if necessary. By the turn of the nineteenth century, the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. had adopted Wahhabism and thrown their formidable maritime forces behind it. While the British were quick to label these raids as acts of piracy, to the Qawasim One of the ruling families of the United Arab Emirates; also used to refer to a confederation of seafaring Arabs led by the Qāsimī tribe from Ras al Khaima. they were part of a ‘life of struggle [jihād]’ for a greater cause (Al-‘Aqqad, p.77).

Britain claimed to be acting to make the maritime trade routes of the Gulf safer for everyone. However, from an Arab perspective, Britain was simply another imperial power seeking the upper hand in the Gulf, as Portugal, France, and the Netherlands had done before them. Moreover, Britain had allied itself with Muscat, which was one of the Qawasim’s main rivals and was actively opposed to the spread of Wahhabism. Indeed, the 1819 expedition had been conducted in cooperation with the Imam of Muscat, Sayyid Sa‘īd bin Sulṭān Āl Bū Sa‘īd, and Britain still continued to provide him with support. In November 1820, Britain and Muscat sent a joint force against the Banī bū ‘Alī, a tribe in southern Oman whom they accused of piracy. Of more concern to the Imam, however, was that the Banī bū ‘Alī had adopted Wahhabism, and were in revolt against his authority. The tribe was eventually defeated, after a prolonged and costly campaign, but the process severely strained Britain’s claim to be acting only to suppress piracy in the Gulf, and not to interfere in local disputes.

Lost in translation?

Not only did Britain struggle to define the limits of its own campaign against piracy, it also found it difficult to communicate these intentions to the local Arab rulers.

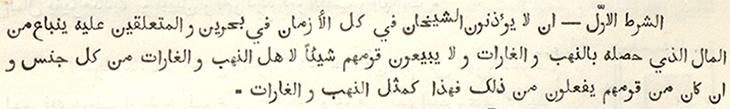

The Arabic word for piracy – qarṣanah – is relatively modern. The Arabic versions of British treaties with Arab rulers in the Gulf throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries suggest that the inhabitants had no specific concept of piracy as separate from maritime warfare or inland hostilities. The Arabic text, both of the 1820 treaty and of a comparable preliminary treaty with the shaikhs of Bahrain in the same year, consistently uses ghārāt (which back-translates as ‘raids’) as the parallel for piracy. Elsewhere, a convention with the ruler of Bahrain, Muhammad bin Khalifah, in 1861 expresses piracy as baṭsh (aggression), while a 1916 treaty with the ruler of Qatar (Abdullah bin Jasim Al Thani) uses al-sariqah fī al-baḥr (theft at sea).

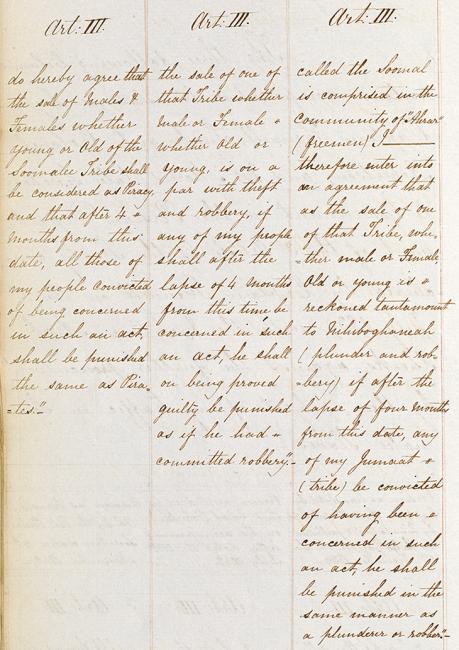

These inconsistencies rendered the treaties susceptible to misinterpretation, as soon came to the attention of the British. In 1842, Lieutenant-Colonel Henry D. Robertson, the officiating Resident in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , raised this issue in relation to a treaty that Captain Samuel Hennell had signed with several of the rulers of the lower Gulf in 1839 to criminalise the slave trade as an offence tantamount to piracy. The Arabic version of that treaty uses nahb (plunder) and ghārāt (raids) in lieu of piracy. Robertson argued that these terms equate piracy (and by extension the slave trade) with common robbery, and a debate over this interpretation ensued. While the British decided ‘not to disturb the existing arrangements’ (IOR/F/4/2014/89998, f. 209r) on this occasion, the debate seems to have alerted them to the elusive nature of the concept of piracy in Arabic.

Dropping the term

In 1853 a Perpetual Maritime Truce was concluded with the same signatories of the 1820 treaty, who now agreed to avoid all maritime hostilities, thereby doing away with the earlier distinction between ‘piracy’ and ‘acknowledged war’. This Truce abandons the term altogether and instead expresses the notion more generally through phrases such as ‘hostilities at sea’ (rendered in Arabic as al-ḥarb wa-l-jidāl fī al-baḥr = ‘war and dispute at sea’) and ‘aggression at sea’ (al-taʿaddī wa-l-taʿarruḍ fī al-baḥr = ‘attack and confrontation at sea’).

The term piracy continued to appear in treaties with rulers in the Gulf into the twentieth century, but its prohibition no longer provided their basis, as it had in 1820. Instead, these treaties now confirmed Britain’s position as the dominant power in the Gulf, henceforth to act as the ‘protector’ of these rulers. Previously referred to by Britain as the ‘Pirate Coast’, the territories of these tribes brought under submission by Britain were now to be known as the ‘Trucial Coast’.

The legacy of “piracy”

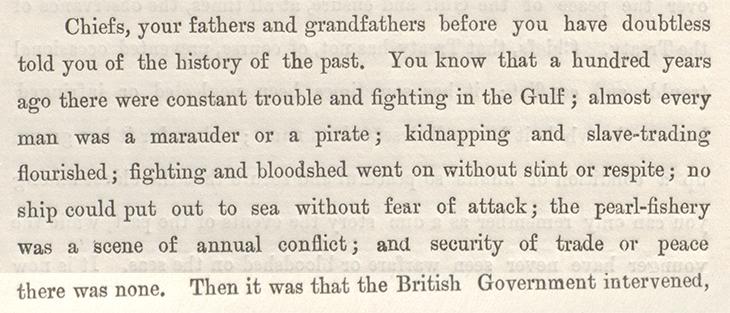

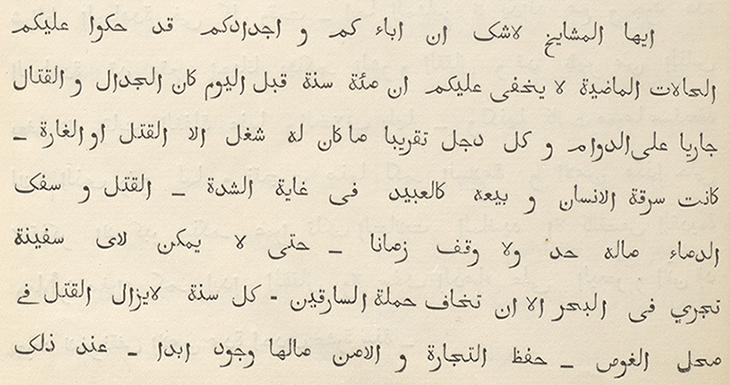

Despite its demise in treaties, piracy continued to appear in Britain’s discourse about the region. In 1903, Lord Curzon (then Viceroy of India) visited Sharjah, where he addressed the rulers of the Trucial Coast A name used by Britain from the nineteenth century to 1971 to refer to the present-day United Arab Emirates. , and provided a historical overview of Britain’s involvement in the Gulf.

The idea of piracy remained central to Britain’s justification for its involvement in the Gulf. As Curzon put it in his address, ‘We found strife and we have created order,’ further insisting that Britain’s presence was still needed, since ‘the peace of these waters must still be maintained’ (IOR/L/PS/10/606, f. 130r-v).

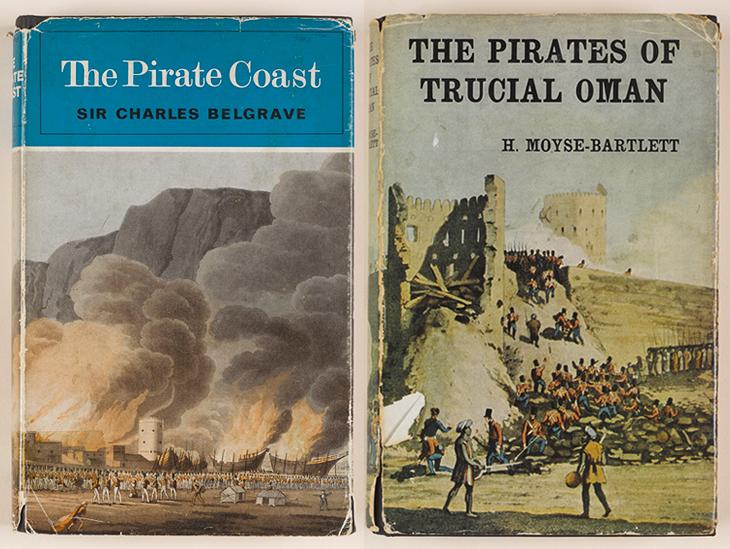

While it is not clear whether all signatories of the 1820 treaty ever held the same interpretation of piracy, it nevertheless continued to provide an important justification for the British presence in the Gulf, right up until their departure in 1971. Despite the difficulty of defining and identifying it, the idea of Gulf piracy proved compelling. Books such as those pictured below, both published in 1966, demonstrate the enduring popularity among British audiences of this story about the pacification of the “pirates” in the Gulf.