Overview

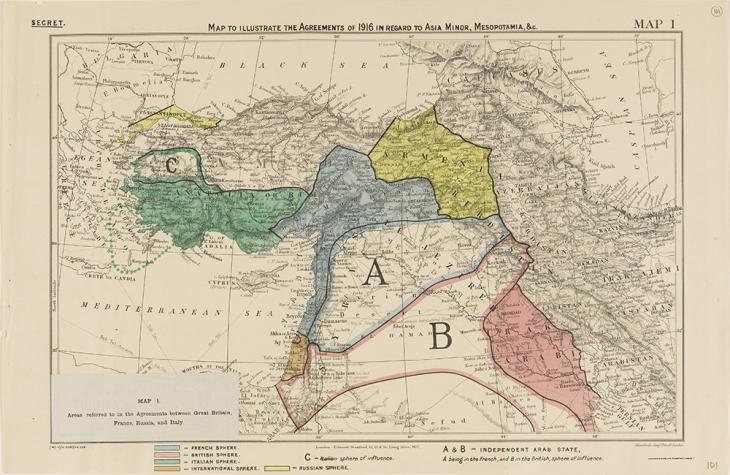

A widespread myth runs that, after the First World War and the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the borders of the Middle East were casually re-drawn ‘in the sand’ by Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot. There are, however, a number of problems with this version of events. Firstly, the region as we know it bears little resemblance to the vision of these two infamous imperial diplomats. Secondly, the archival material in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records shows that the real story behind Arabian borders involved much more intrigue than the simple stroke of a pen.

The Case of Saudi Arabia

In the 1920s, Jordan was known as Transjordan Used in three contexts: the geographical region to the east of the River Jordan (literally ‘across the River Jordan’); a British protectorate (1921-46); an independent political entity (1946-49) now known as Jordan : an inexactly defined, hardscrabble part of Britain’s Palestine Mandate, under semi-autonomous Arab government. With its borders jutting out and zigzagging across the map, Jordan is the subject of a particularly colourful myth: Winston Churchill is sometimes quoted (apocryphally) as boasting that he created Jordan ‘one Sunday afternoon in Cairo’. However, the border as we now know it was largely shaped in fits and starts, in response to local developments.

At this time, south of the British and French Mandates, another new state was taking shape in the post-Ottoman power vacuum. From Najd in central Arabia a King, backed by Wahhabi tribal levies, was forging a vast kingdom that would later bear his name: Ibn Saud.

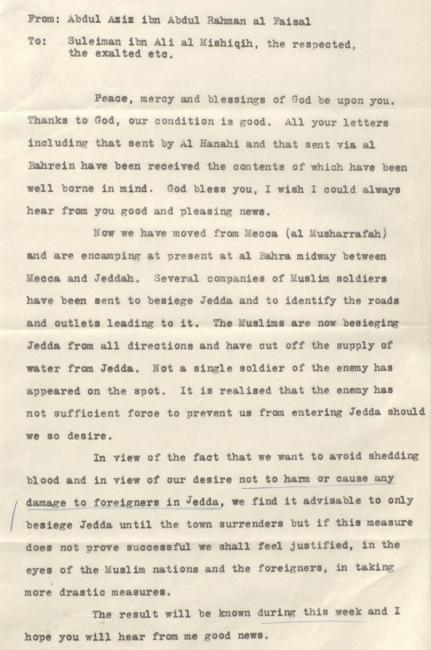

As the Mandates were solidifying, Ibn Saud, with whom Britain had struck a deal against the Ottomans during World War I, pushed into Asir and towards the Holy Cities, grappling with his great rival Husayn bin Ali al-Hashemi, the King of Hejaz, for control of Mecca and Medina. In 1916, encouraged by British promises (later broken) of a vast, independent Arab kingdom, Husayn had initiated the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans. Now, facing defeat, Husayn abdicated and went into exile, leaving his son Ali in Jeddah to lead the desperate resistance against Ibn Saud.

The Buffer Zone

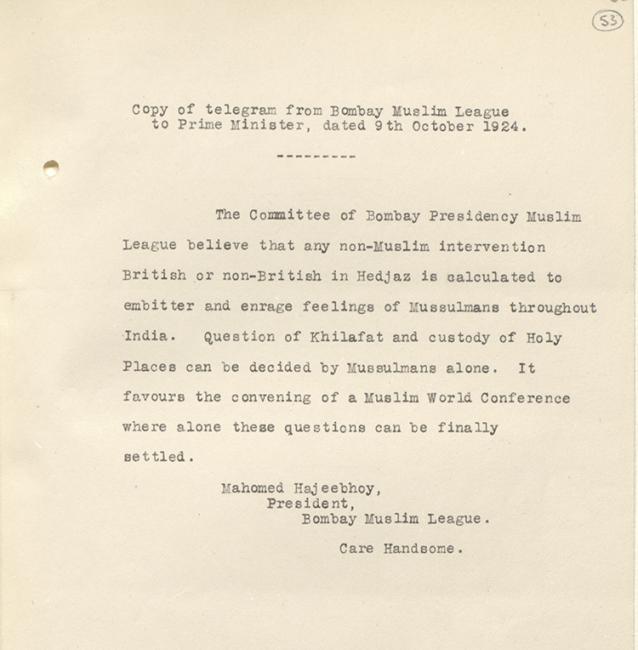

Britain maintained a studied neutrality as its two old allies wrestled over control of Arabia, yet the conflict and the rise of Saudi power cast a long shadow over the British imperial system. The warring sides both recruited and proselytised in British colonies including Palestine, Egypt, Aden, India, and Malaya. Meanwhile Muslim associations in India warned London against intervention in the Hejaz- Transjordan Used in three contexts: the geographical region to the east of the River Jordan (literally ‘across the River Jordan’); a British protectorate (1921-46); an independent political entity (1946-49) now known as Jordan conflict.

Meanwhile in 1924 Ibn Saud’s forces carried out raids into Transjordan Used in three contexts: the geographical region to the east of the River Jordan (literally ‘across the River Jordan’); a British protectorate (1921-46); an independent political entity (1946-49) now known as Jordan and almost made it as far as Amman, threatening Britain’s precarious project in the Levant A geographical area corresponding to the region around the eastern Mediterranean Sea. , before they were driven back by the Royal Air Force. The British feared that the conflict could easily spread throughout Transjordan Used in three contexts: the geographical region to the east of the River Jordan (literally ‘across the River Jordan’); a British protectorate (1921-46); an independent political entity (1946-49) now known as Jordan , where the Hashemite descendants of the exiled Husayn ruled (and still do).

Britain’s fear would have a decisive impact on shaping the modern border. Throughout the 1920s, the southern frontier of today’s Jordan – particularly around the town of Ma’an – changed hands between Transjordan Used in three contexts: the geographical region to the east of the River Jordan (literally ‘across the River Jordan’); a British protectorate (1921-46); an independent political entity (1946-49) now known as Jordan and Hejaz. As Ibn Saud advanced, the British worried that if the retreating Hashemites were able to regroup in Ma’an it might provoke a Saudi attack, and thus bring the conflict dangerously close to Mandatory Palestine. After much debate, Britain finally brought Ma’an into Transjordan’s orbit to keep the war to the south at arm’s length. To this day, the city of Ma’an remains a part of Jordan.

Wadi Sirhan: the Clayton Mission

This alone, however, was not enough to safeguard Britain’s imperial presence in the region. London had to come to terms with a major emerging power. Thus, a high-level envoy was dispatched to meet Ibn Saud, and begin to smooth out various thorny issues in Anglo-Saudi relations, including borders. The envoy chosen was Gilbert Clayton, a veteran Middle East operator and former Director of Intelligence in Cairo.

Clayton departed in late 1925 with his interpreter George Antonius, a Lebanese-Egyptian man-of-letters employed by the British in Palestine who would prove invaluable during the negotiations with Ibn Saud.

The delegation landed in besieged Jeddah, managed to avoid engaging with the beleaguered King Ali, and headed for the Saudi battle camp. Thereafter, an Anglo-Saudi relationship was negotiated over several weeks. The Transjordanian border proved an especially sticky point, due to competing claims over Wadi A seasonal or intermittent watercourse, or the valley in which it flows. Sirhan - the particularly sheer triangle of border sometimes called ‘Winston’s Hiccup’ in reference to the abovementioned apocryphal account. Both sides wanted control over the town of Kaf. For Britain, control of its fortress was deemed necessary to head off future raids and to insulate Transjordanian tribes from the spread of Wahhabi influence. Some feared that if Ibn Saud took Wadi A seasonal or intermittent watercourse, or the valley in which it flows. Sirhan, he would win over the Ruwallah tribe and thereby extend his influence as far as the Syrian border, cutting off Iraq from Palestine and the Mediterranean, and jeopardising Britain’s grand plans for railways, air routes, and pipelines.

Ibn Saud, meanwhile, was unwilling to concede Kaf and wanted to keep his trade routes to Syria unobstructed. Despite many rounds of negotiations and some veiled threats, Ibn Saud would not move from his stated position.

Eventually Clayton capitulated, conceding Kaf in exchange for a guarantee that the town and its surroundings would be demilitarised. After some more back-and-forth concerning pasturage rights, the boundary was fixed a short distance outside the town. It was subsequently enforced on the ground by demanding official permits from tribes and merchants attempting to cross.

There would be further minor exchanges of territory until the 1960s, but in substance the Saudi-Jordanian border as it exists today had been established. Not drawn carelessly across the map either by diplomats in Paris or by Churchill in Cairo, the border was shaped by a Saudi king, a British agent, and a Lebanese interpreter in a tent outside Jeddah, in response to local political demands.

A story behind every border

Just as the Saudi-Hashemite war has been etched onto the world map, every border that we now take for granted was made in the interests of particular groups (very often, colonial powers), according to the pressures, imperatives, and threats of their historical moments. Though largely forgotten now, these stories can still be found in the documents preserved in colonial archives.