Overview

In 2018, the Royal Navy returned to its historic base in Juffair, Bahrain. In 2020, it was announced that another large British naval base would be developed in Duqm, Oman. Both events are part of a longer history of a British presence in the Gulf that began with the East India Company. In this history of tensions, naval bases have been focal points both for Britain’s imperial order in the Gulf, and the opposition to it.

Both British and Gulf Arab politicians and military leaders have often evoked the historic relationships between Britain and the Arab states of the Gulf in relation to today’s surviving bases. Yet, for over a century, British naval bases in the region were built and located off the coast of Iran.

From Napoleon to Reza Shah

The idea of Britain occupying an island in the Gulf for use as a strategic base can be traced back to the Napoleonic Wars. With Napoleon occupying Egypt, and courting Iran and the Ottoman Empire, British officials were haunted by the spectre of an attack on their colonies in India via Iran or the Gulf. From 1800, the East India Company officer John Malcolm proposed occupying an island in the Gulf, and using it if necessary as a base to promote separatism in Ottoman Iraq and southern Iran. Malcolm considered that this strategy would free the British Government in India from its dependence for security on diplomatic relations with neighbouring powers, allowing it to contain a potentially pro-French Tehran and Constantinople, and secure British control of the Gulf. Malcolm almost put this plan into effect in 1808, preparing an expedition to occupy Kharg island, but the strategy was ultimately abandoned in favour of diplomacy with Tehran.

![Excerpt of a letter by the Governor General of Bengal Lord Minto regarding the establishment of a British base on the ‘Island of Kharrack […] for the security of our Interests’, 31 October 1808. IOR/L/PS/9/67/57, f. 7v](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_l_ps_9_67_57_0014_crop_web.jpg?itok=0SX4qrdu)

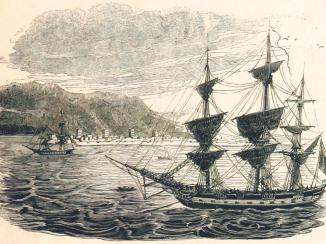

Immediately after the 1819 “anti-piracy” expedition to the Gulf, the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. revived the idea of a permanent base in the region. Major-General William Grant Keir, the expedition’s commander, sent officers to scout suitable islands off the Iranian coast, and sent back reports to Bombay describing the navigability, availability of supplies, and population of Kish and Qeshm islands.

The Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. subsequently instructed Henry Willock, Britain’s Chargé d’Affaires in Iran, to solicit the Qajar government to cede an island to Britain to serve as a permanent base. Although Willock claimed that the sole aim of the proposed base was to suppress “piracy”, the Qajars were unenthusiastic about the proposal and wary of having foreign forces on their doorstep.

Despite Iran’s opposition, British troops occupied Qeshm in 1820, citing verbal permission from the Imam of Muscat, who also claimed the island. This met with strong Iranian objections, and Iranian ministers demanded the withdrawal of British forces. They also suggested that Husayn ʿAli Mirza Farmanfarma, the Prince-Governor A Prince of the Royal line who also acted as Governor of a large Iranian province during the Qājār period (1794-1925). of Fars, who governed Iran’s Gulf coast, take responsibility for combatting “piracy” in the region. British officials scorned this offer.

![Excerpt from a translation of a note by the Sadr-e ’Azam [Prime Minister] and Mu’tamid al-Dawla [Foreign Minister] of Persia, proposing that the Prince of Fars ‘check piracy’ in the Gulf, 1820. IOR/L/PS/9/69/51, f. 2v](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_l_ps_9_69_51_0004_crop_web.jpg?itok=f3O5wLv8)

The occupation of Qeshm lasted until 1822. An abortive agreement in that year between Farmanfarma and the Resident in Bushire, William Bruce, granted Qeshm to Britain for five years, but also recognised Iranian suzerainty over Bahrain. This was immediately disavowed by Bombay, and Bruce was sacked. Iran never otherwise recognised the British occupation of Qeshm. Not wanting to jeopardise diplomatic relations with Tehran, Bombay eventually backed down and withdrew from the island.

The following year, however, British boots were back on the ground, uninvited, on Qeshm. Basaidu, on the island’s western tip, then became the first permanent British naval base in the Gulf, housing a coaling station, hospital, and other amenities. No permission was ever granted by Iran.

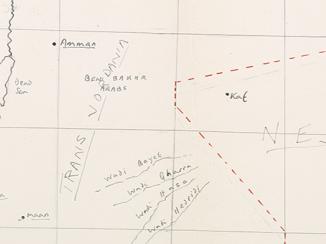

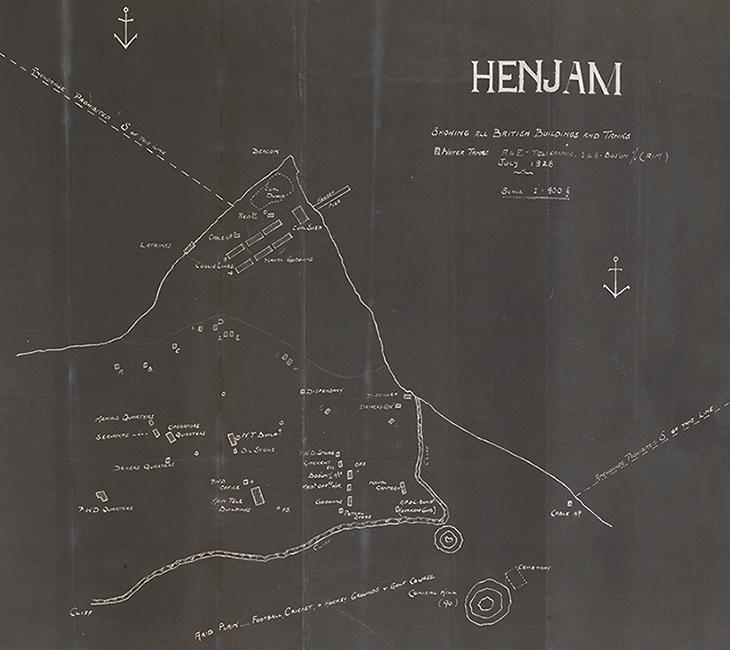

In 1913, though some facilities in Basaidu were retained, the main naval base was moved to Hengam island (also claimed by Muscat, but recognised by Britain as Iranian territory). British officials deemed Hengam to have a better climate and a more strategic location by the Straits of Hormuz. Coal depots, recreation grounds for sailors, and other facilities were built on the island, while British warships docked in its harbour. In 1920, after the British occupation of Iraq, Hengam was also used to incarcerate political prisoners deported from Iraq. These included Kurdish leaders Jalal Baban and Shaikh Mahmud Barzanji (IOR/R/15/6/392, ff. 27v, 29r). All this was again without Iran’s permission: the Iranian government had only granted a concession for a telegraph station.

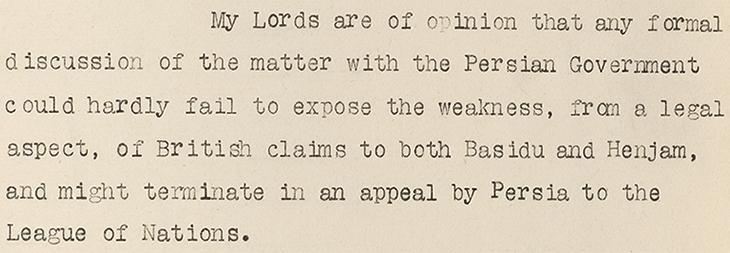

Following his rise to power in the 1920s, Reza Shah Pahlavi sought to assert direct control over Iran’s southern coast, end colonial encroachment on Iranian territories, and set Anglo-Iranian relations on a more equal footing. Consequently, British officials were forced to reckon with the status of the two bases. Some tried to find a legal justification: Francis Beville Prideaux, Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , wrote in 1926 that as Basaidu ‘has been occupied as British territory for over a hundred years without the permission of the Persian Government it is ours now prescriptively as much perhaps as is Aden!’ (IOR/L/PS/10/1095, f. 945v). Others, however, were forced to admit that Britain had no rights over the islands. Charles Walker of the Admiralty wrote in 1927 that ‘any formal discussion of the matter with the Persian Government could not fail to disclose the weakness, from a legal aspect, of British claims’ to either site.

Under pressure from Reza Shah, Britain ultimately abandoned both bases in 1935. The main naval base was relocated to Juffair, with a subsidiary on the Musandam Peninsula in Oman. Thereafter, Britain’s presence in the region was tied to the shaikhdoms on the other side of the Gulf.

Nodes of imperial power

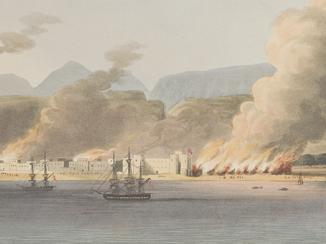

Wherever they were located, naval bases were an essential part of the infrastructure that enabled Britain to enforce its policies in the Gulf. Bases provided supplies, forward positions, communications, and other facilities to sustain Britain’s coercive naval power. Iran, meanwhile, had been right to be wary of the presence of British arms at such close quarters, as British warships turned their guns against Iran several times throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including during the 1856-57 Anglo-Persian War. After Iran’s attempt to annex Herat in Afghanistan, British warships bombarded and occupied several Iranian ports to force Iran’s withdrawal. The war was facilitated by the base at Basaidu, which provided resupply and a forward position for coordinating naval operations. During this war the British Government in India reinforced the base, judging it ‘useful not only as a coaling station but as a port of call for orders and information at the head of the Gulf’ (IOR/L/PS/20/C248, f. 34v). Thus, a colonial war on Iran was enabled by a base that squatted on its territory.

These sources in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records reveal a history of tension and aggression arising from the presence of British bases in the Gulf. This history should be remembered when considering Iran’s opposition to the long-term presence of Western bases and warships in the region today.