Overview

During the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), Britain’s colonial possessions in India were a tempting target for France. India was a significant source of Britain’s wealth, and a convincing threat was guaranteed to draw British attention and resources away from the conflict in Europe. Consequently, Napoleon sought to invade India via Persia. The India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records reveal Britain’s response, which drew it into deeper involvement in both Persia and the Gulf.

Napoleon’s Eye on India

Napoleon had contemplated attacking India as early as 1798, at the same time as he had invaded Egypt and Syria and attempted to form an alliance with the Sultan of Mysore, Tipu Sultan, against the British. In 1805, another opportunity arose when the Shah of Persia, Fath Ali Shah Qajar, appealed for military assistance against the Russian Empire.

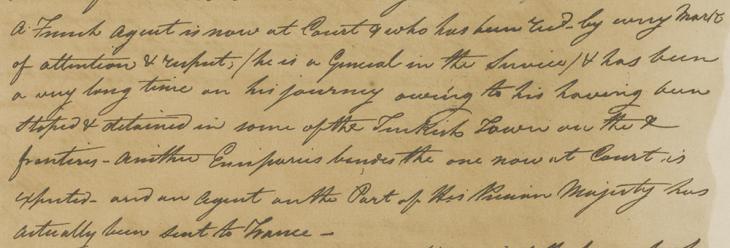

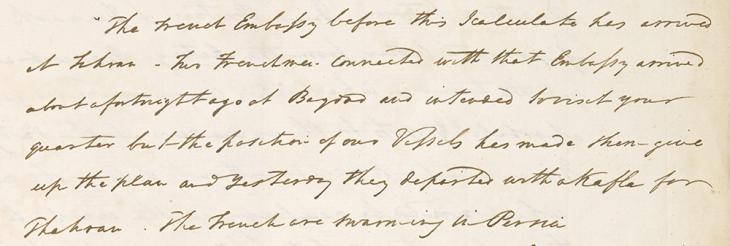

The Shah sought British and French assistance following Russia’s invasion of Persia’s Caucasian provinces in 1804. Seizing the opportunity, Napoleon dispatched two envoys in 1805, whom the British observed warily. The Bushire Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. diary for 1806-1807 includes a number of reports on the arrival of one of the envoys, Pierre Amédée Jaubert, who reached Tehran in October 1806.

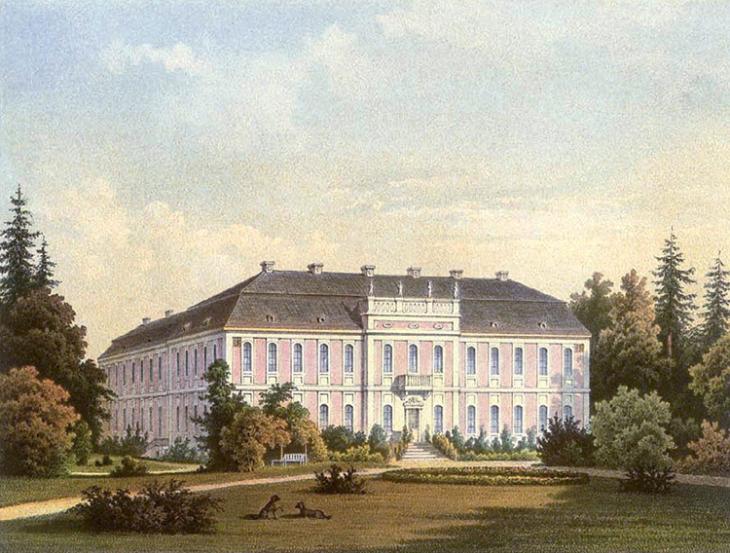

The Shah had been impressed by Napoleon’s victories in Europe and agreed to send an envoy. Thus, Mirza Muhammad Ridha Khan Qazvini met with Napoleon at Finkenstein Palace in Austria, where they signed a treaty of alliance in May 1807. Napoleon agreed to provide military and diplomatic assistance against Russia, while the Persians agreed to sever ties with the British and allow a French army to march through Persia to India.

Napoleon promptly dispatched a military mission, led by General Claude-Mathieu de Gardane, which arrived at Tehran in December 1807. Gardane was to provide military assistance and assess the viability of an overland invasion of India.

British Positioning in the Gulf

Reports of the deepening Franco-Persian ties caused concern in both London and Bombay. The British had already begun to recognise the strategic importance of the Gulf for the defence of India during Napoleon’s earlier campaign in Egypt and Syria. To stymie French influence in the region, Britain had established the Baghdad Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. in 1798, and dispatched envoys to Persia, Mehdi Ali Khan in 1798 and John Malcolm in 1800. Malcolm’s mission, legendary in Persia for its splendour, had resulted in a political and commercial treaty in 1801.

By 1807 British intelligence reports were sounding the alarm about an army of 12,000 troops, led by the veteran general Jacques-François Menou, marching towards India through Persia. In November the Acting Resident at Baghdad, John Hind, wrote to the Resident at Bushire, Nicholas Hankey Smith, about the expected arrival of General Gardane’s embassy at Tehran, warning that ‘the French are swarming in Persia’.

John Malcolm’s Second Mission

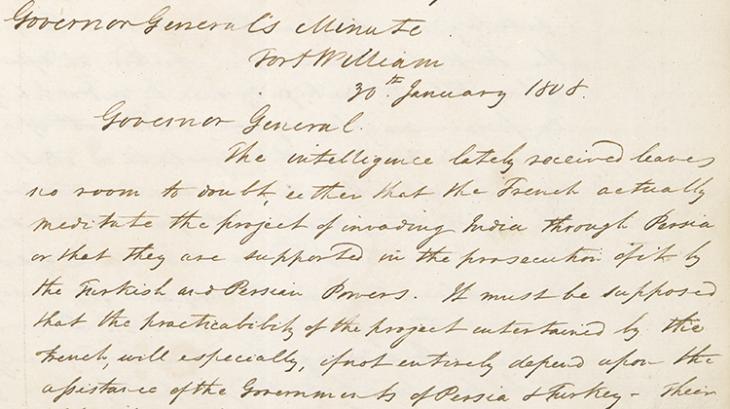

Meanwhile in Calcutta, the Governor-General of Bengal, Lord Minto, was afraid that even a small French force could wreak havoc in India. Believing there to be ‘no room for doubt, […] that the French actually mediate the project of invading India through Persia’, Minto dispatched John Malcolm on a second mission to Persia.

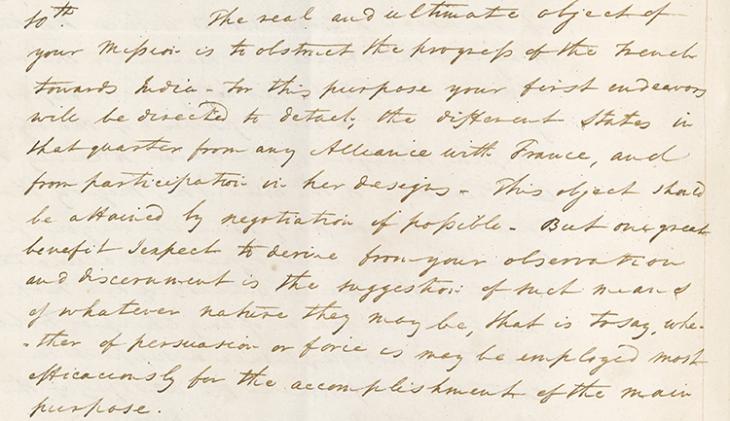

The main purpose of Malcolm’s mission was to obstruct French progress towards India but he had also long been in favour of establishing a British outpost in the Gulf, advocating strongly for a base on the island of Kharg at the head of the Gulf.

Draft instructions mediated by the Supreme Council of Bengal in January 1808 indicate that while Malcolm was expected to work through ‘negotiation if possible’, he should also consider ‘such measures of whatever nature they may be, that is to say, whether of persuasion or force’.

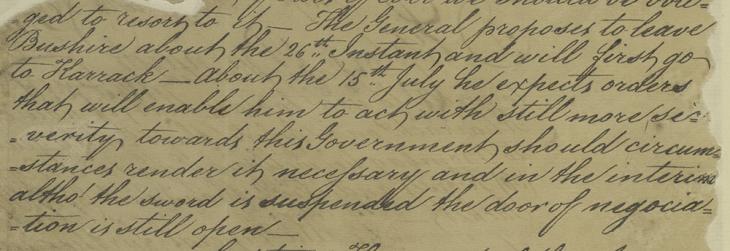

Malcolm arrived in Bushire in May 1808, accompanied by an escort of 500 troops. Here he was detained by the Persians on account of Gardane’s presence in Tehran. Frustrated by the delay, Malcolm threatened to occupy Kharg. Nicholas Hankey Smith reported to the Resident at Basra, Samuel Manesty, that Malcolm had proposed to make for Karrack [Kharg], but was expecting orders that would allow him to ‘act with still more severity towards [the Persian] Government should circumstances render it necessary.’

However, without express permission from Minto and realising that landing on Kharg would spark hostilities between Britain and Persia rather than undermine the French, Malcolm backed down and re-embarked for Bombay in June 1808.

Enter Sir Harford Jones

Following Malcolm’s departure, a second British envoy was dispatched to Persia. Independently of Minto, the British Government in London had appointed Sir Harford Jones as HM Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary A diplomatic representative who ranks below an ambassador. The term can be shortened to 'envoy'. to Persia in February 1807. Following delays and a long journey, Jones arrived at Bushire the following October.

His arrival proved timely. By that autumn Napoleon had failed to assist Persia in its conflict with Russia, undermining the commitments made at Finkenstein and causing Gardane’s mission to fall out of favour with the Shah. Consequently, Jones was allowed to proceed to Tehran, and his mission signalled a fatal blow to the already precarious Franco-Persian alliance. Gardane left Tehran only days before Jones arrived on 14 February 1809.

Gardane’s departure saw the decline of Napoleon’s hopes for an overland invasion of India, and by March Jones had concluded a preliminary treaty with Persia, shutting out the French. Ratified in 1814, the treaty laid the groundwork for closer ongoing Anglo-Persian ties.

Fleeting Threat, Enduring Reverberations

Napoleon’s alliance with Persia, however fleeting, had enduring consequences. By highlighting the strategic importance of the region, the French threat spurred Britain to force the French out of Persia completely, and encouraged the Government of India’s latent interest in establishing a base in the Gulf.

These concerns over the defensibility of India would become more pressing throughout the nineteenth century. While Napoleon’s threat to British interests was extinguished with his defeat at Waterloo in 1815, the succeeding years would see significant British expansion in the Gulf as Britain sought to establish control over shipping lanes and protect the approaches to India.