Overview

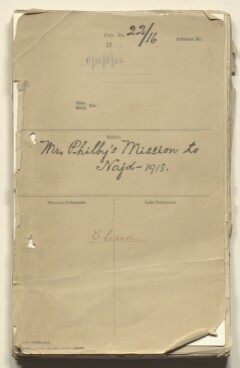

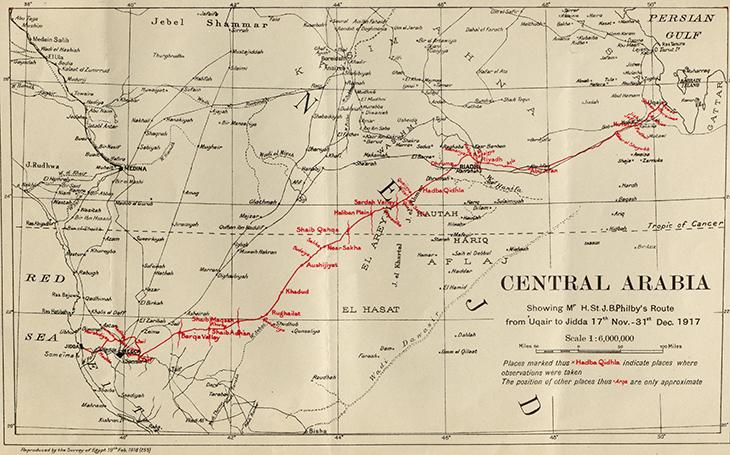

In 1917, Harry St John Bridger Philby was working in Basra as Financial Assistant to Percy Cox, the Chief Political Officer of the Indian Expeditionary Force. In mid-October, Philby convinced his superiors to send him as head of a mission to cross the desert from Uqair on the Gulf to Riyadh. There he was to rendezvous with Robert Hamilton, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. at Kuwait, and meet with Ibn Sa‘ud, the Amir of Najd and Hasa in central Arabia.

‘Abd al-‘Aziz bin ‘Abd al-Rahman Al Sa‘ud, commonly referred to as Ibn Sa‘ud, was the rising leader in central Arabia. He had reconquered Riyadh in 1902 on behalf of his father from arch rival ‘Abd al-‘Aziz bin Mit‘ib al-Rashid (known as Ibn Rashid) to found the third Saudi state. During the First World War, Ibn Rashid was allied with the Ottoman Empire, against Britain and the Allies. The primary objective of Philby’s mission was therefore to discuss with Ibn Sa‘ud ‘what further action [he] can usefully take to further common cause against the enemy’ (IOR/R/15/1/747, f. 4v). It was also important for Britain to maintain good relations so that Ibn Sa‘ud would remain ‘a British vassal for good’ and not himself turn to the Ottomans (IOR/L/PS/10/387/1, f. 65v). Another key objective was to improve relations between Ibn Sa‘ud and Husayn bin ‘Ali al-Hashimi, Sharif of Mecca, both of whom were on friendly terms with Britain. Finally, the mission sought to smooth over discord between Ibn Sa‘ud and Shaikh Salim bin Mubarak Al Sabah of Kuwait, to allow an effective British blockade of the Ottomans and Ibn Rashid.

En route to Basra from Cairo in May, Philby had been briefed in Baghdad by Major Gertrude Bell, the first female Military Intelligence Officer in the British Army. At that time, she was advising the British Government on Middle East policy, following her earlier archaeological and intelligence gathering expeditions in Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and the Arabian Peninsula. She was exceptionally well-placed to brief Philby ahead of his mission, having written a report a year earlier on the occasion of Ibn Sa‘ud’s visit to Basra that described his ascent to power and his relationship with Britain.

Practical and Diplomatic Logistics

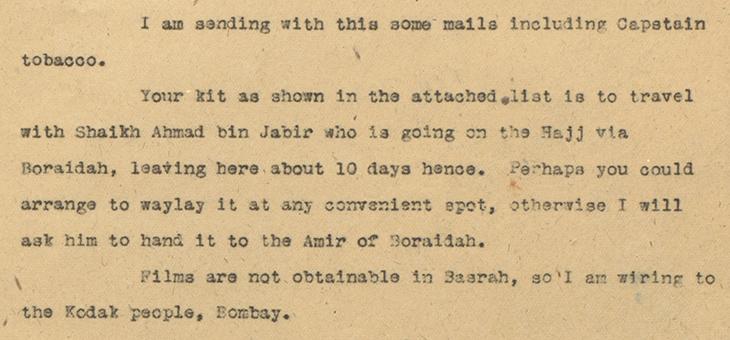

As with any expedition, the preparation of supplies and kit was essential. Among Philby’s many requests were ‘ten one pound tins [of] tea, three hundred good cheroots, five hundred Egyptian cigarettes, two pounds [of] Capstain [sic] tobacco’ (IOR/R/15/5/66, f. 68r). The records document Philby’s eventually successful attempt to procure an aneroid thermometer to measure air pressure, and Kodak photographic film for the camera he had already bought in Basra. These instruments were vital for taking barometric readings and for recording the terrain.

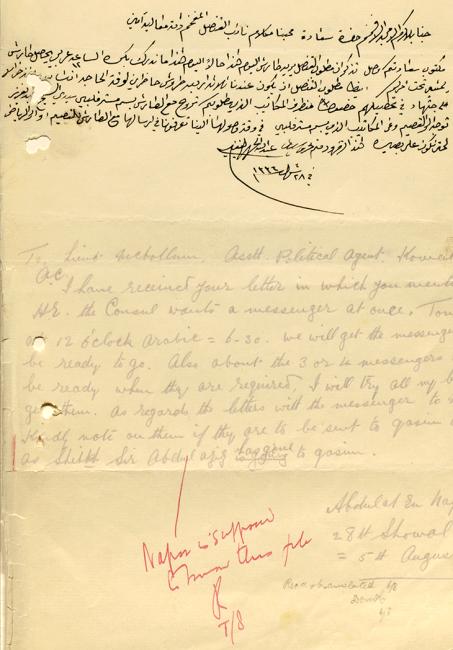

Philby also received logistical help from Abdullah al-Nafisi, a Najdi with commercial interests in Kuwait who acted as Ibn Sa‘ud’s agent in the country. Often involved in dealings with Britain, al-Nafisi smoothed the path for Philby’s journey by providing messengers, and later in September 1918 also facilitated the supply of one thousand rifles by Britain to Ibn Sa‘ud.

Extravagant gift exchange was standard diplomatic practice. On arrival at Hofuf on 21 November 1917, Philby asked Percy Loch, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. at Bahrain, for twelve gold and twelve silver watches, presumably to present either to the local Amir or to Ibn Sa‘ud. Writing from Riyadh the following year, Philby noted that ‘Ibn Saud is very short of tents’ (IOR/R/15/5/66, f. 158r), and requested the dispatch of six good tents as gifts for Ibn Sa‘ud and his family, and a further fifty for his men. Ibn Sa‘ud reciprocated with a pair of Arabian oryx for King George V.

Taking Notes and Gathering ‘Colonial Knowledge’

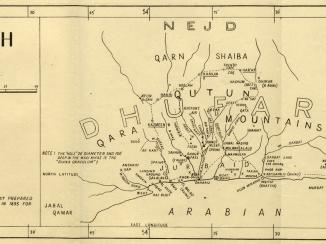

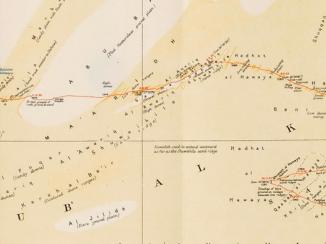

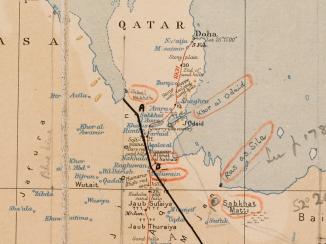

Philby’s meticulous notes and correspondence cover both his preparations and the journey into the interior itself. During the journeys first to Riyadh and later onwards to Taif, Philby undertook pioneering cartographical research. He noted the topography in extensive detail, and collected numerous ‘specimens of the wild life’ for the British Museum’s natural history section (IOR/R/15/2/295, f. 225r). The British Museum later named a species after Philby (Philby’s Partridge, Alectoris philbyi), which had hitherto been unknown in the West. He also recorded information on the inhabitants of regions he passed through, noting for example the number and composition of the population in Diriyah.

On arrival in Riyadh, his note taking continued, as he paced the city walls to draw up a map of the settlement and its outer limits. In addition, he instructed Colonel F. Cunliffe-Owen, the mission’s military adviser, to compile a report on both the general military situation in central Arabia and Ibn Sa‘ud’s specific prospects to attack Ibn Rashid. Read through a critical contemporary understanding of imperialism, this accumulation and collation of information during the expedition can be seen as constituting the gathering of ‘colonial knowledge’, which art historian Phillip B. Wagoner defines as ‘those forms and bodies of knowledge that enabled European colonizers to achieve domination over their colonized subjects around the globe’ (p. 783).

A Lifetime of Travels in Arabia

From Riyadh, Philby sent word back to officials in Iraq that he was planning to continue to Jeddah on the Red Sea, and he departed before his superiors could refuse. After Philby arrived at Jeddah on the last day of 1917, the Sharif of Mecca denied him permission to retrace his steps back to Riyadh. He therefore travelled on to Cairo, where he spent some time before setting out by boat in February to return to Riyadh via eastern Arabia. Next, Philby undertook an exploration of Southern Najd, including Wadi A seasonal or intermittent watercourse, or the valley in which it flows. ad-Dawasir, an ancient route used to bring coffee from Mokha in Yemen into the interior. His meticulous report covers geographical, meteorological, agricultural, demographic, and historical information.

All this was the start of a lifetime of exploration of the Arabian Peninsula. On Philby’s death in Beirut in 1960, fellow explorer Wilfred Thesiger wrote, ‘As an Arabian traveller I shall always be proud to have followed in his footsteps’ (p. 565).