Overview

In the 1940s British authorities in the Gulf were facing a conundrum. Before the advent of the oil era, medical care in the region had mostly been provided by doctors of the American Mission. Seeking to expand on existing hospitals in Bahrain and Muscat, American missionary doctors had approached Shaikh Abdullah bin Jasim Al Thani with the idea of building one in Qatar. In September 1946 Ernest Vincent Packer, the British representative of Petroleum Concessions in Bahrain and Qatar, informed British colonial officials that the Shaikh of Qatar was building a hospital. This appears to have put British officials on the back foot, as they could hardly resist an offer for the provision of healthcare, but were reluctant to promote an American venture. As the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain summarised at the time: ‘I feel disinclined to help in the establishment of an American assisted dispensary […] There is, however, need for medical facilities at Dohah [sic] and I would like to be in a position to assist the Shaikh’ (IOR/R/15/2/608, f. 4r). Despite the obvious benefits, British officials were wary of providing an avenue for the growth of American influence in Qatar, where Britain had held sway since the First World War.

Establishment of Britain’s position in Qatar

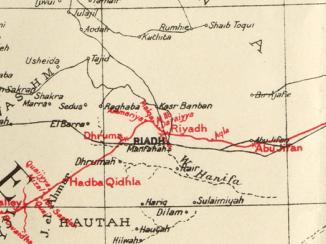

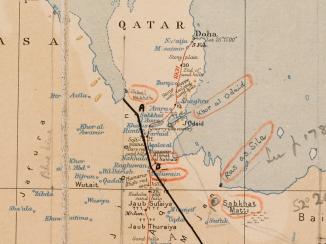

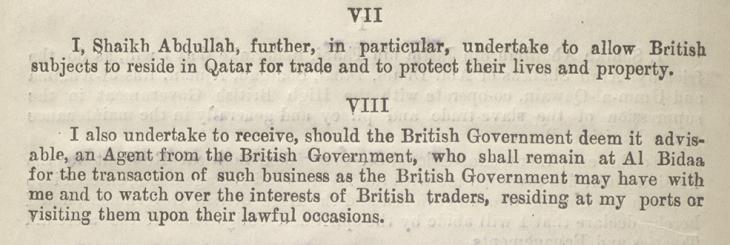

Although British recognition of the Al Thani family in 1868 had been instrumental in the creation of Qatar as a distinct political entity, Britain’s main concerns at that time had been the suppression of maritime warfare. As in other Gulf shaikhdoms during that period, Britain had minimal involvement in Qatar’s internal affairs. Ottoman influence had been recognised until the 1913 Anglo-Ottoman Convention, then the Shaikh of Qatar and the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , Percy Cox, had signed the Qatar Treaty in 1916. This contained a provision for Britain to post an agent in Doha, but this clause had not been implemented by 1946, and British relations with the Ruler of Qatar were still being conducted through the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain.

A Medical Officer Who Could Combine Two Functions

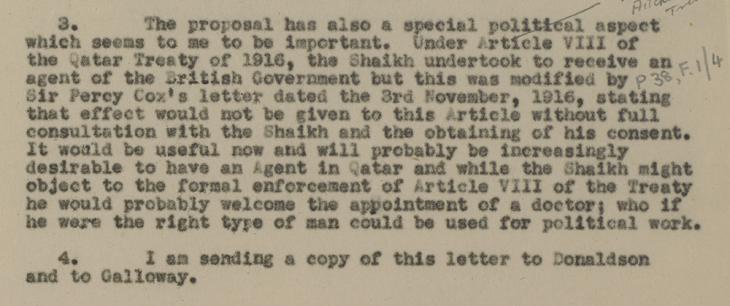

In the immediate years after the Second World War, the British felt a pressing need to provide medical services to those working in the burgeoning oil industry in Qatar. In December 1946 the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , Rupert Hay, wrote to the Government of India to inquire about the possibility of funding for a dispensary in Doha. Reasoning that it ‘will probably be increasingly desirable to have an Agent in Qatar’, Hay conjectures that the doctor could informally serve two functions, as the ‘right kind of man could [also] be useful for political work’.

Hay felt it would be preferable if Shaikh Abdullah agreed directly to the appointment of a political officer, but was prepared ‘to employ the subterfuge of a doctor’ if necessary.

A Parsimonious Perspective and the Erosion of Britain’s Position

However, the Government of India responded that, in light of India’s approaching independence from Britain, and until future financial arrangements had been clarified, there was no possibility of agreeing to the necessary funding. Writing to Hay in January 1947, G. C. L. Crichton of the External Affairs Department, New Delhi, confirms ‘that until the position regarding separation of His Majesty’s Government and India’s interests in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. region has been cleared it is not possible for us to pursue this or any other scheme which involves expenditure from Indian revenues’ (f. 9r).

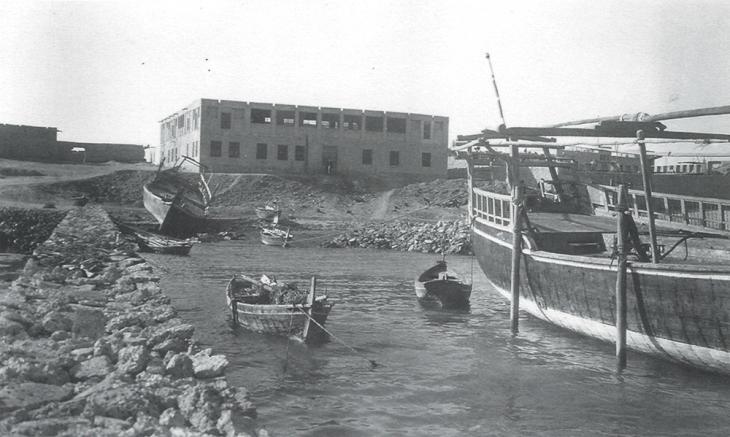

Furthermore, British officials concluded that there was little to be gained from attempting to roll back the American Mission’s nearly-completed hospital. While they may have been relieved not to have to bear the responsibility or the expense, the British nevertheless deemed it ‘unfortunate from our point of view that medical facilities at Qatar should have fallen into American hands’ (f. 20r). This might have been because it represented another foot in the door for American influence in the Gulf. By contrast, Dr Storm of the American Mission wrote to the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain, claiming that they saw the Doha facility merely ‘as an Out-Patient development of the American Mission Hospital in Bahrain’ (f. 15r).

Moreover, in a letter to the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain, Shaikh Abdullah stresses his desire to provide better health facilities in Qatar and points out that the dispensary is a ‘philanthropic project’ (mashrū’ khayrī).

A Dispensary for Doha: Britain and the development of healthcare in the Gulf

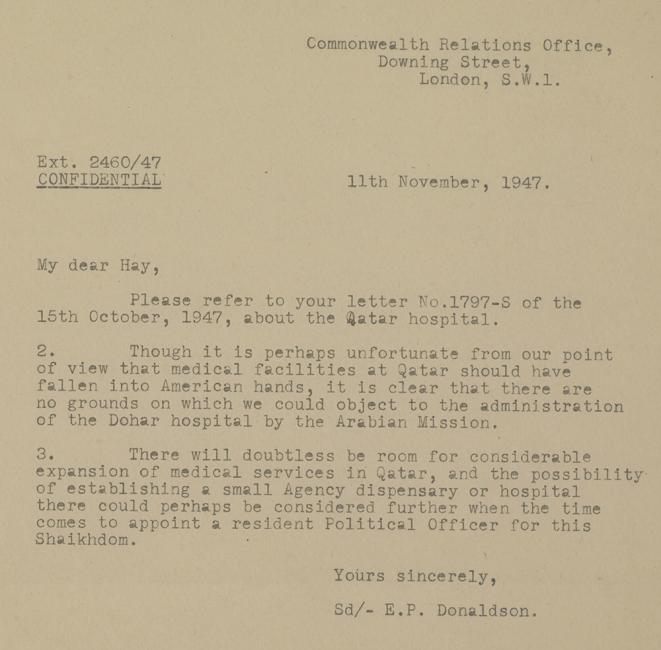

In wrapping up this episode, Eion Pelly Donaldson of the Commonwealth Relations Office concludes philosophically that while ‘there are no grounds on which we could object’ to the American hospital, ‘there will doubtless be room for considerable expansion of medical services in Qatar, and the possibility of establishing a small Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. dispensary or hospital there could perhaps be considered further’.

Despite this apparent flurry of interest in the late 1940s, British authorities displayed little intrinsic concern over the health of the residents of the Qatari Peninsula. It was only when this issue became intertwined with the expansion and development of the oil industry, as well as fears about the potential growth of American influence in Doha, that British officials focussed their attention on health provision in Qatar.