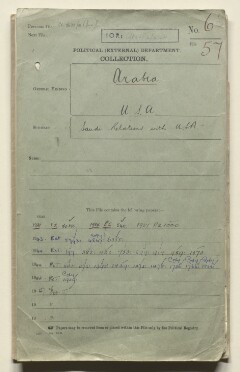

Overview

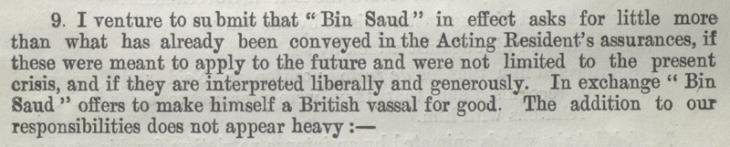

By 1932, friendly relations between Britain and the ruling house of Āl Sa‘ūd had been firmly established. The British Government recognised the advantage of securing the goodwill of Amir ‘Abd al-‘Azīz bin ‘Abd al-Raḥman Āl Sa‘ūd (popularly known as Ibn Sa‘ūd) during the early stages of the First World War, when he was considered a potential ally against the Ottoman Empire. In January 1915, during a mission to offer Ibn Sa‘ūd (then titled Amir of Nejd, Hasa, and its Dependencies) a treaty of alliance with Britain, political officer Captain William Henry Irvine Shakespear remarked on Ibn Sa‘ūd’s potential as a ‘British vassal for good’, not just during the current war, but also well into the future. A treaty was signed later that year, and a second, known as the Treaty of Jeddah, was concluded in 1927.

1932 onwards: the reasons behind friendly relations

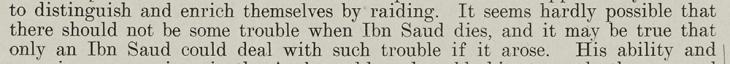

The conciliatory approach taken by the British Government in its relations with Ibn Sa‘ūd was a reflection not only of the latter’s position as the most powerful ruler on the Arabian Peninsula, but also of the British perception of him as the living embodiment of the Saudi state. The strategic importance of retaining Ibn Sa‘ūd’s goodwill, and ensuring the stability of the country was such that there were growing concerns among British officials, from the 1930s onwards, about the continuity of the regime in the event of Ibn Sa‘ūd’s death.

Ibn Sa‘ūd had his own reasons for displaying loyalty to the British. In its early years, the newly-formed Saudi state was largely reliant on the Hajj pilgrimage for revenue. However, this income alone proved insufficient, prompting Ibn Sa‘ūd to seek regular financial assistance from the British Government. The country’s economic prospects appeared to improve dramatically with the discovery of commercial quantities of oil at Dhahran in 1938, five years after the Saudi Arabian Government had granted its first oil concession. However, oil extraction, and the prosperity that it promised, were postponed by the outbreak of the Second World War. The revenue from the Hajj pilgrimage was also disrupted, since the British deemed it too dangerous for pilgrim ships to travel by sea from India to Saudi Arabia. All of this, combined with food shortages, left the Saudi Government dependent on financial aid from Britain (and later from the United States) for the duration of the war.

Relations in wartime

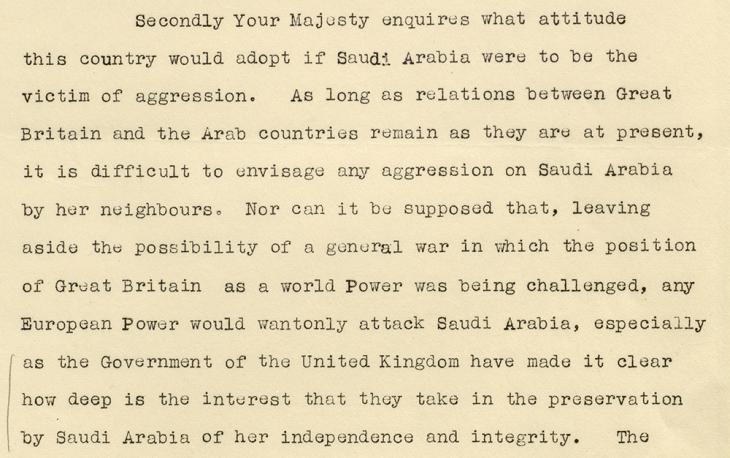

In addition to financial assistance, Ibn Sa‘ūd requested assurances from the British regarding relations between the two countries. In January 1939, Ibn Sa‘ūd wrote to the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, asking the latter to clarify his country’s position on various matters, including the nature of Britain’s response in the event of Saudi Arabia being attacked by a foreign aggressor. In his reply (drafted on his behalf by the Foreign Office) Chamberlain judged an attack on Saudi Arabia – either by its neighbours, or by a European power – as highly unlikely, yet failed to guarantee British support in such a scenario. Nevertheless, the response stressed Britain’s deep interest in ‘the preservation by Saudi Arabia of her independence and integrity.’

Despite this non-committal response, there were concerns at both the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. and the Foreign Office about the possibility of Saudi Arabia falling under the influence of Germany or Italy, and there was considerable relief when, following the outbreak of the Second World War, Ibn Sa‘ūd adopted a position of benevolent neutrality. The financial assistance provided by the British to the Saudi Government during the early years of the war was largely motivated by concerns that Ibn Sa‘ūd’s regime might otherwise collapse and leave the country vulnerable to the influence of the Axis powers.

Post-war changes: decline of British influence

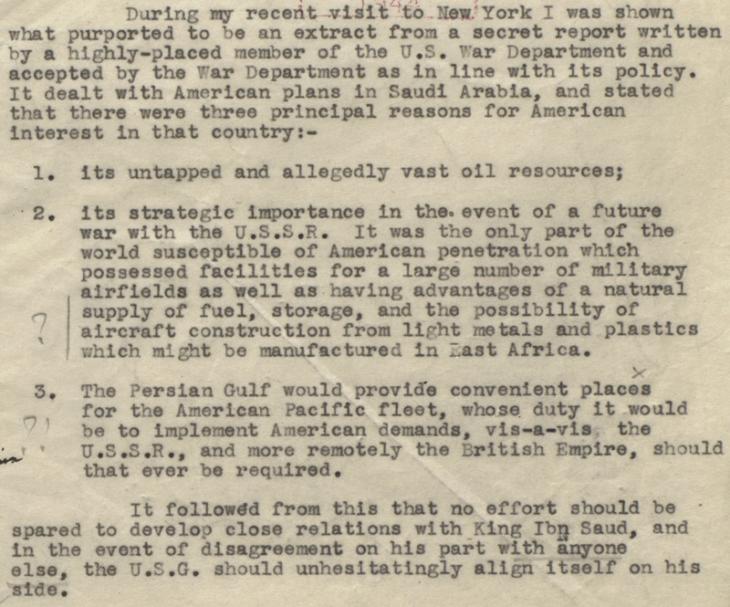

After the war ended, oil production resumed in Saudi Arabia, and the country’s fortunes were transformed. Britain maintained friendly relations with Ibn Sa‘ūd, but its influence in Saudi Arabia had already begun to decline. The presence of the Californian Arabian Standard Oil Company in Saudi Arabia from the mid-1930s onwards had led to an increase in the US Government’s interest in the country’s affairs, resulting in the appointment of a US Consul at Dhahran in 1944. Earlier that same year, the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, who was employed in intelligence gathering at the British Embassy in Washington, DC, had seen an extract from a secret report by the United States War Department, which outlined the long-term strategic interests of the US in Saudi Arabia, and recommended that ‘no effort should be spared to develop close relations with King Ibn Saud’.

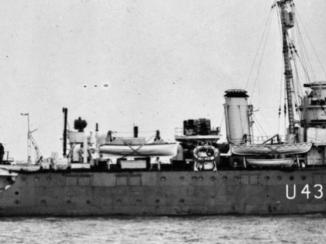

Berlin’s intelligence was received with some scepticism by Foreign Office officials, but proved to be a remarkably prescient statement of the United States’ intentions for the post-war era. A meeting between Ibn Sa‘ūd and President Roosevelt on board USS Quincy in February 1945 strengthened relations between the two countries, and marked a significant turning point. Having replaced Britain as Saudi Arabia’s key western sponsor and protector, the United States would also soon become the predominant imperialist power in the Middle East.