Overview

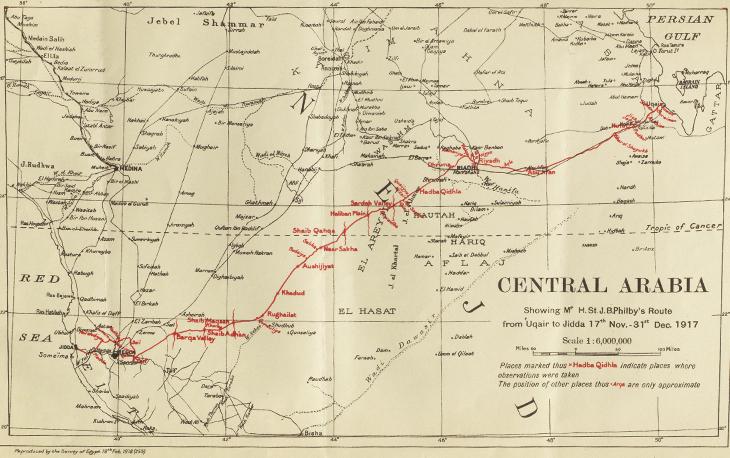

Harry St John Bridger Philby (1885-1960), who once called himself ‘the first Socialist to enter the Indian Civil Service’, led a British diplomatic mission to Ibn Saud, the Amir of Nejd and future King of Saudi Arabia, in 1917-18. He soon found his loyalties drifting away from his employers and towards the man with whom he was supposed to be negotiating. In 1924, having resigned from his position as Head of the Secret Service in Mandatory Palestine, Philby settled in Jeddah, in present-day Saudi Arabia, and became Ibn Saud’s chief adviser in his dealings with Britain and other Western powers.

Supporting the Saudi cause

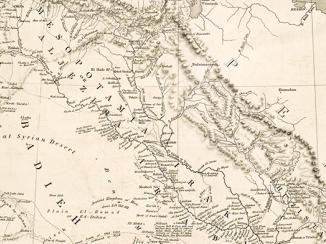

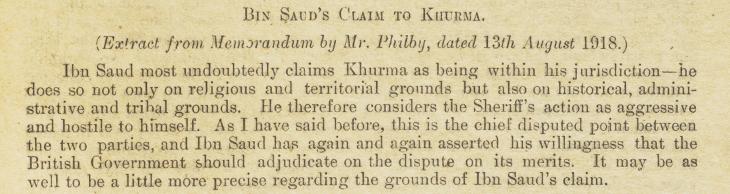

Having initiated the Arab Revolt in 1916, Hussein bin Ali Al Hashimi, Sharif of Mecca and leader of the Revolt, proclaimed himself ‘King of the Arabs’, but he faced a rival claimant in Ibn Saud. Although British policy supported Sharif Hussein, it only went so far as to recognise him as King of the Hejaz. Philby, meanwhile, quickly began to favour Ibn Saud and even provided him with confidential information to assist his cause. An India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. memo written by Philby in 1918 outlined the grounds for supporting Ibn Saud’s claim to the Al-Khurma Oasis, which soon afterwards became the subject of the First Nejd-Hejaz War.

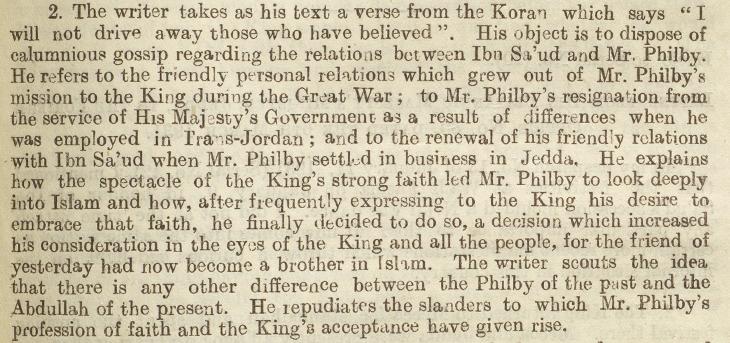

Conversion to Islam

In 1930 Philby took the significant step of converting to Islam, which afforded him both greater access to Ibn Saud and the right to enter the holy city of Mecca. Cecil Hope Gill, British Chargé d’Affaires at Jeddah, reported meeting with Philby soon afterwards, stating that ‘He made no pretence whatever that his conversion was spiritual’, but that it was a long-deliberated decision arising in response to his ‘disassociation from British ideals’ (IOR/L/PS/12/15, f. 44r).

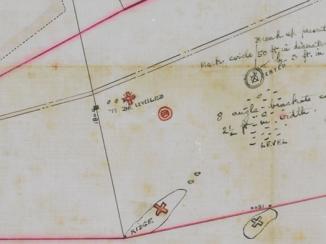

Ibn Saud may have been among those with doubts about Philby’s motivations for conversion, as he continued to delay granting the necessary permissions for Philby to fulfil his greatest ambition of becoming the first Westerner to cross the Empty Quarter or Rub’ al Khali Desert. Philby was beaten to that goal by Bertram Thomas, an adviser to the Sultan of Muscat and Oman, but he nevertheless led an expedition across the desert in 1932, which resulted in the production of one of the first maps of the Rub’ al Khali.

‘Anti-British’

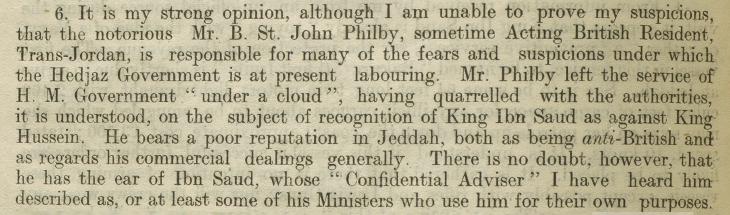

Philby’s transfer of loyalty was noticed in his native country and became a frequent topic of discussion. In 1929 the Commander of HMS Clematis wrote from Jeddah that Philby was ‘responsible for many of the fears and suspicions under which the Hedjaz Government is at present labouring’ and that Philby had a reputation as being ‘anti-British’.

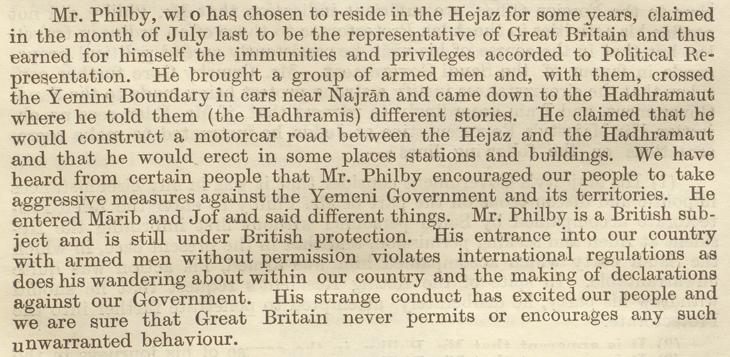

In 1936 Philby led an expedition through the Hadhramaut in central Yemen, which was perceived by both the British and the Yemenis as a propaganda tour for Ibn Saud’s claim over the region, including parts of the British-administered Aden Protectorate. ‘Presumably Mr Philby still calls himself an Englishman’, wrote the Acting Resident in Aden. ‘It is all the more to be deplored, therefore, that he should deliberately work against the interests of Great Britain’ (IOR/L/PS/12/2071, f. 21v).

In 1940, a year after standing for Parliament for the far-right British People’s Party, Philby was arrested in Bombay as a suspected Nazi sympathiser, deported to England and briefly interned. Nevertheless, shortly after his release, he successfully recommended his son Kim Philby to the British secret service. Philby eventually lost his influence in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia after openly criticising Ibn Saud’s son and successor, King Saud bin Abdul Aziz Al Saud, following his accession to the throne in 1953. Philby died in Beirut in 1960, while visiting Kim. His last words were reported to be: ‘I am so bored.’