Overview

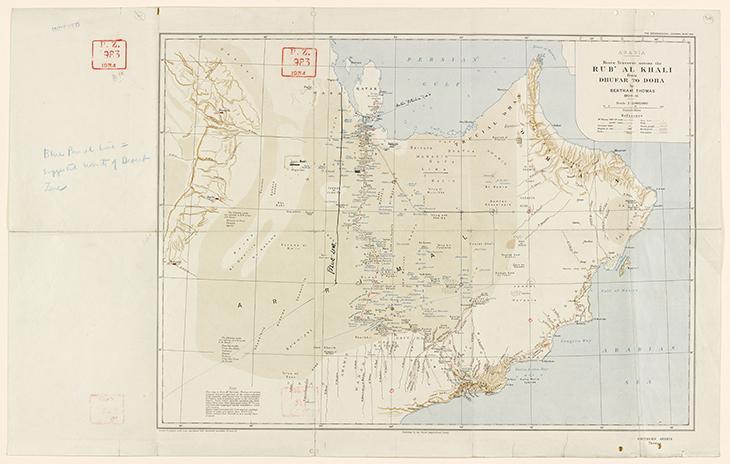

When the press first reported the crossing from Dhofar to Doha in 1931, it was accompanied by observation of oil seepages that ensured its publication as front-page news.

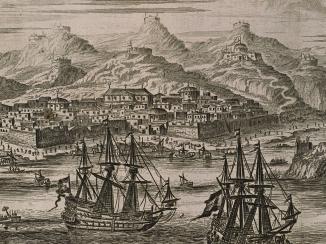

However, after this initial burst of publicity, Bertram Thomas slipped out of the limelight into relative obscurity. He first arrived in Muscat following his appointment as British financial advisor, or wazir Minister. to Sultan Taimur bin Faisal after the First World War.

Skull measuring and anthropology

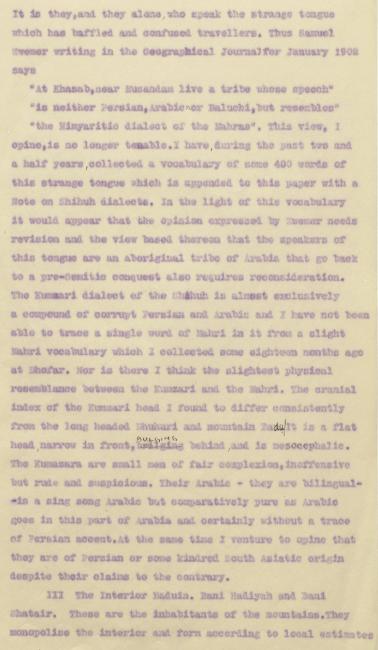

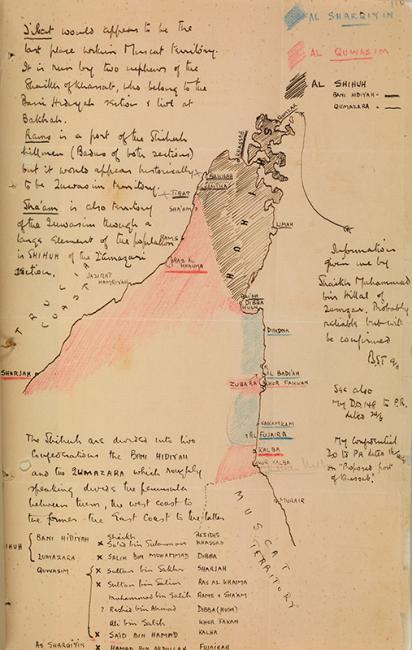

Thomas combined his official duties of bringing a semblance of order to the budget of the ‘Muscat State’ with a passion for exploration. He honed his skills with trips to the region around the Musandam Peninsula, where he sought to identify the allegiances of different tribes to assist in dispute resolution and tax collection. However, true to the colonial origins of anthropology, he also measured the skulls of the inhabitants (a practice he was to continue in Dhofar): “The cranial index of the Kumzari head I found to differ consistently from the long headed Dhuhari and mountain Padu [Bedu]. It is a flat head, narrow in front, bulging behind and is mesocephalic”.

The expedition begins

Thomas first engaged in a number of preparatory expeditions to Dhofar, where he earned the confidence of the tribes that would later help him make the crossing. Then in early October 1930, without any word to British officials in the Gulf, Thomas sailed from Muscat to Dhofar on an oil tanker belonging to the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. He almost had to abandon the expedition because of a tribal feud that detained his guide - Shaikh Saleh bin Kalut al Rashidi al Kathiri - who only managed to turn up at the last moment.

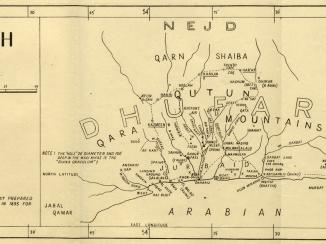

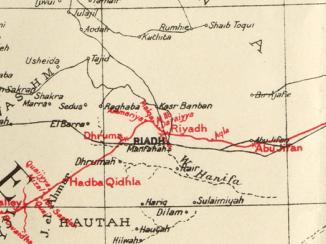

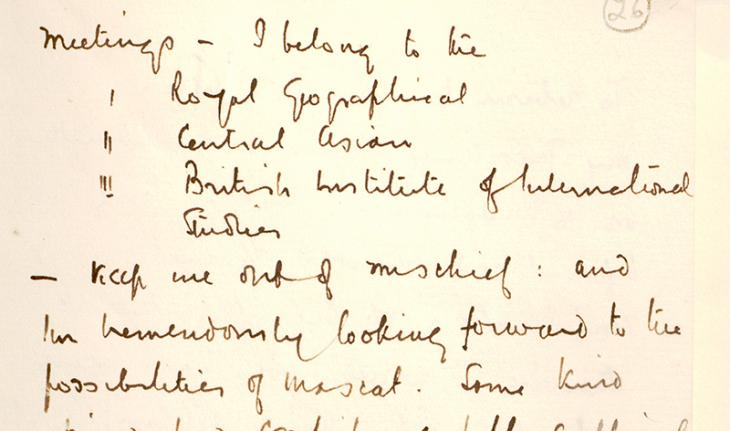

The two started off from Salalah, Dhofar on 10 December 1930, enduring extreme hardship and the constant threat of ambush by warring tribes to arrive in Doha, Qatar fifty-nine days later. Thomas carried with him a range of instruments for map-making, including a prismatic compass, hydrometer, and sextant, which he used to compile his map of ‘South East Arabia’ that would later become a standard reference work on the subject. He kept detailed notes on the flora and fauna that he encountered, sending many specimens back to the Natural History Museum in London, where on his return he also presented a series of papers to the Royal Geographical Society on the discoveries made during his expeditions.

American perceptions

However, Thomas’s expeditions were regarded with scepticism by certain British and American officials, in contrast to the receptiveness shown by the scientific community. The US Consul in Baghdad, Alexander K. Sloan, questioned the Agent of the Mesopotamia Persian Company, Mr. Walker, on a visit to Bahrain in February 1931 as to the exact purpose and motivations behind Thomas’s crossing from Dhofar to Doha: “Mr Walker immediately defended him stating that British officials stationed in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. were well aware of the fact that Mr Thomas had not been sent to act as financial adviser to the Sultan of Oman solely, but that his main duties there were to explore the interior and to try and locate for the Anglo-Persian Oil Company oil seepages reported to have been discovered by Arab caravans in that section of Arabia. He added that British officials were also aware of the fact that an Anglo-Persian Oil tanker had picked up Mr Thomas at Muscat and had landed him at Dhafur [sic] and that his journey while ostensibly undertaken as an exploratory trip over an unknown portion of Arabia was also taken to obtain all information possible for the Anglo-Persian Oil company” (See Porter 1982: 28-32).

This range of duties is not reflected in the correspondence of India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. officials. In April 1931 the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , Hugh Vincent Biscoe, wrote: “When his successor arrived, it was found that the greatest laxity had been allowed to prevail in the financial administration of the State …the above facts show, I think that he has little interest in his work, and that he has neglected his duties. He has been in the employ of the State for 5 years on a large salary, and has not in my opinion rendered that loyal service that the State had a right to expect” (IOR/L/PS/12/46 ff. 642-644).

Late recognition

Hence, while it was suggested that Thomas deserved recognition for making the crossing, decisive support for a full knighthood was not forthcoming. It was only in 1949 that the Most Distinguished Order of St Michael and St George was conferred on him, in part explaining why he has been rather neglected in the annals of exploration and empire.

Nevertheless, in December 2015, an Anglo-Omani expedition including the British explorer Mark Evans, MBE, and Shaikh Mubarak Saleh Muhammad Saleh bin Kalut, the great-great-grandson of Shaikh Saleh bin Kalut, set out “in the footsteps of Bertram Thomas” to retrace the 1930-31 expedition. Following this 85th anniversary crossing honouring the achievement of Thomas and his Omani guide Shaikh Saleh bin Kalut, more attention is now being given to this enigmatic desert explorer.