Overview

The Imam of Muscat

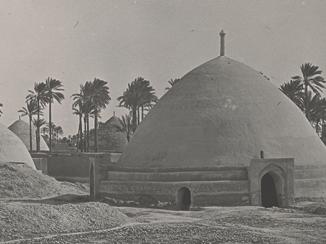

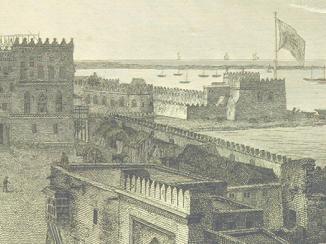

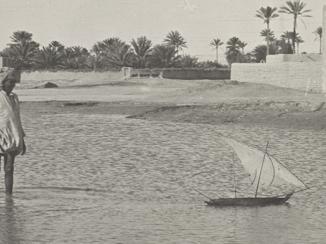

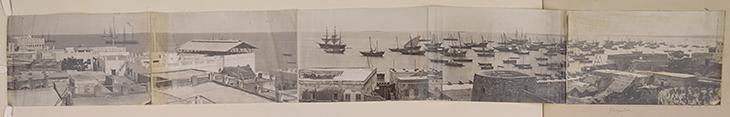

Sa‘id bin Sultan Al Bu Sa‘id (r. 1804-1856) was very powerful in the nineteenth century. Referred to in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records as the Imam of Muscat, he held territories extending from Oman as far as Zanzibar and the east coast of Africa. When he moved his court to Zanzibar in 1840, leaving Muscat in the hands of one of his sons, the British Agent in Muscat, Captain Atkins Hamerton (1804-1857), moved with him. Hamerton’s letters to his superiors in India at this time are overwhelmingly concerned with the trade in enslaved people, which the Imam was reluctant to suppress as it formed a large portion of his revenue. However, there were other forms of trade available at Zanzibar, which made it an attractive place for British merchants to establish themselves. Hamerton himself was also preoccupied with observing other Europeans. British hegemony was not as well-established around Zanzibar as it was in the Gulf, and France was a strong rival in the area, as it controlled Réunion (then called Bourbon) and was likewise active in Madagascar.

Britain was not just concerned with the Imam on account of trade. Oman was a powerful force in the Gulf, and the Imam still exerted great influence over the region, even if he had left its day-to-day management to his son. British officials saw Muscat as a steadying and friendly force in the Gulf, and did not want the Imam to favour French or American interests over their own.

Letters from Hamerton

Hamerton reported rumours of French movements, even when Britain and France were supposedly at peace. He was particularly concerned by indications that France was going to establish a presence elsewhere near Zanzibar, including on the islands off Madagascar and the Seychelles. There were frequent reports that French officers had been spotted at Nosy Be, and that the Imam had agreed to let them settle there.

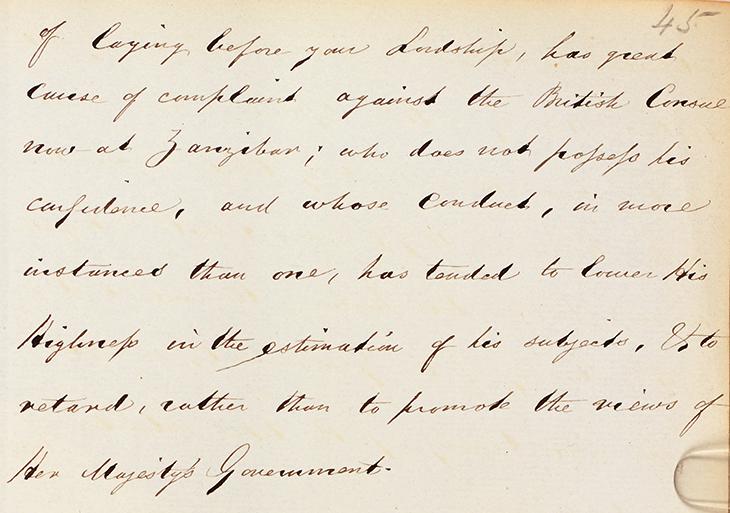

Hamerton’s position was isolated, which may explain why he so faithfully recorded any perceived slights to British prestige. He noted the actions of French and American actors at Zanzibar with suspicion, believing that they were trying to discredit Britain as much as possible, which may have been true to a certain extent. His own standing was not helped in 1842 when the Imam’s representative in London, Sayyid ‘Ali bin Nasir al-Busa‘idi, told George Hamilton-Gordon, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, that the Imam had lost confidence in Hamerton.

Soft power exchanges

In this climate, small actions took on greater significance. In 1821, a British army officer reported that the Imam had some French porcelain, which he seemed to prize greatly. The officer therefore suggested that Britain should provide him with a chandelier for his new palace, together with a ‘complete set of cut glass’ (IOR/F/4/711/19405, f. 129r). The British Governments in India decided to outdo the French by also adding a set of British porcelain depicting views of England.

Hamerton noticed a change in the Imam’s attitude towards him when the sloop of war Lily arrived in 1841, captained by Commander John Allen. The Imam’s advisors had previously been in the habit of talking loudly so ‘that [Hamerton] might hear them, of the power and wealth of America’, but this soon stopped, and the Imam became far more friendly towards him (IOR/F/4/1959/85480, f. 171r). The Imam prevented two ships from sailing, which Hamerton had been asking him to do, and he even changed the paintings in his reception room; two pictures depicting an American taking a British ship were replaced with two of the Battle of Navarino. The positive impression was furthered by the good personal relationship between Hamerton and Allen.

Hamerton nevertheless still perceived American machinations at work. He blamed their behind-the-scenes manipulations for the Imam’s suspicion that the British Government did not know, and/or did not control the actions of the East India Company. This suspicion led ‘Ali bin Nasir to approach the British Government directly. He appealed to them to prevent the Company from trying to persuade the Imam to give up the trade in enslaved people from East Africa to the Gulf.

Another serious incident came in 1842. Hamerton describes British merchants being forced to sign a declaration that they would no longer consider themselves British subjects, would thenceforth become citizens of Zanzibar of their own free will, and would not invoke British protection. Hamerton told the Imam that the British Government would still protect these people. The Imam responded that he had been informed that living for a long time in America made someone an American citizen. Yet, Hamerton refused to accept that these people could be forced to renounce their British citizenship, solely because they had been residing in Zanzibar.

Practical disputes over trade continued in Zanzibar, with customs officials appearing to prefer trade with Americans. Hamerton meanwhile complained that British merchants were being locked out of the trade in gum copal, ivory, muskets, powder, and piece goods.

A broader pattern

Across the Gulf, larger rivalries played out on small stages, from questions of gifts, to whether a permanently-resident British Agent should be ranked higher than a visiting French Consul. These small signs hinted at broader political tensions, and spotting them could warn agents about changes in opinion before they became official policy.

_0001.jp2/full/!240,/0/default.jpg)