Overview

Civilians living through the First World War in countries where they were not nationals were often interned. Across the British Empire, civilians were sometimes transported over long distances: German citizens living in British East Africa and the Gulf were usually shipped to India. The Ottoman Empire’s policy of internment was less widespread, but some British and French citizens and officials were interned in Turkey. For the ruling powers, the internment posed challenging logistical issues, associated both with moving large numbers of people during wartime, and with managing the personal and business affairs of detainees over the duration of the War.

The British in Baghdad

John Calcott Gaskin began working as the Commercial Assistant to the British Consul at Baghdad in 1906. On 22 November 1914, seventeen days after Britain had declared war on the Ottoman Empire, he was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment for throwing a portion of the ammunition belonging to the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. Guard into a river. In December, the Ottomans transported him out of Baghdad, along with the other British Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. staff. However, some British citizens were kept at Baghdad. When the British were advancing towards there in October 1915, the Ottomans attempted to exchange them for Ottoman officials from Al-Kut whom the British were holding in India. The Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. staff were initially sent to Aleppo, and then, with the exception of Gaskin, taken on to Constantinople (Istanbul), from which they were repatriated. Gaskin remained interned in Aleppo with the other British citizens, but was later sent to Constantinople where he spent the majority of the War.

At the outbreak of the War, the Turkish Government interned some British, French, and Russian citizens who were residing in Ottoman territory. Others were arrested as the conflict continued, but no wholesale internment was ordered. However, many British and French civilians lost their jobs working at the ports, as these were closed to international traffic, and in trying to make their way home became stranded in Athens. On 28 December 1917, Britain and Turkey signed an agreement allowing for a mutual exchange of civilian prisoners. Some Ottoman citizens living in Britain at the outbreak of the War had also been interned, although many Armenians, Syrian Christians, and Ottoman Greeks were designated ‘friendly’ and remained at liberty. In June 1915 there were only ninety four Ottoman subjects in internment camps in Britain, while 493 subjects were registered in Britain, but not interned.

The problem of Gaskin

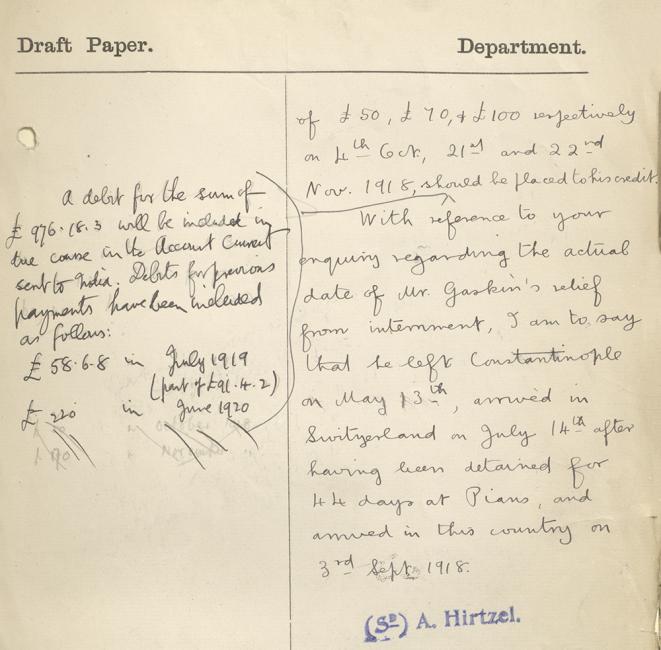

Just as when soldiers were captured and imprisoned their own country continued to pay their salaries, the British continued paying their interned government staff, as they were still in British service. While Gaskin was interned, the main difficulty for the British authorities was administering his salary, and the effects of this were still causing problems as late as 1928. The neutral governments of the Netherlands and the United States administered his pay from Constantinople, and later claimed the money back from the British Government, but they overpaid him due to a misunderstanding about the exchange rate. The ‘official’ rate of exchange, as paid to military prisoners of war in Turkey, was about 133 piastres to the British pound, whereas Gaskin had been paid about 250 piastres to the pound, leaving him significantly better off.

In August 1918, Gaskin was transferred to Switzerland to be repatriated. Again, it was the financial issues which concerned the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. . The British Government paid for his journey from Switzerland to England, and David Monteath, Private Secretary to the Under Secretary of State, raised a question over whether Gaskin should repay that money. Gaskin was subsequently appointed to Mesopotamia, and he successfully argued that his passage there should be paid for, as it had not been his choice to return to England.

Everyone to India

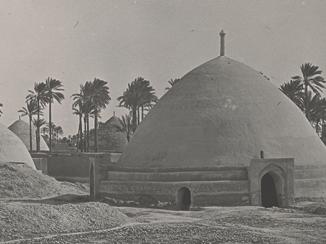

The German, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman citizens whom the British interned were sent to Ahmednagar, an internment camp in Maharashtra, western India. Ahmednagar had earlier been a British military base, and had previously been used as an internment camp during the Second Boer War (1899-1902). Seven internees from the German firm Robert Wönckhaus & Co were held there during the War.

![Postcard published by ICRC showing a view of the camp’s courtyard at Ahmednagar. Image courtesy of ICRC archives [ACICR C G1]](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/c_g1_a_06_0004_0176_0001-lightbox.jpg?itok=a5mL6Crc)

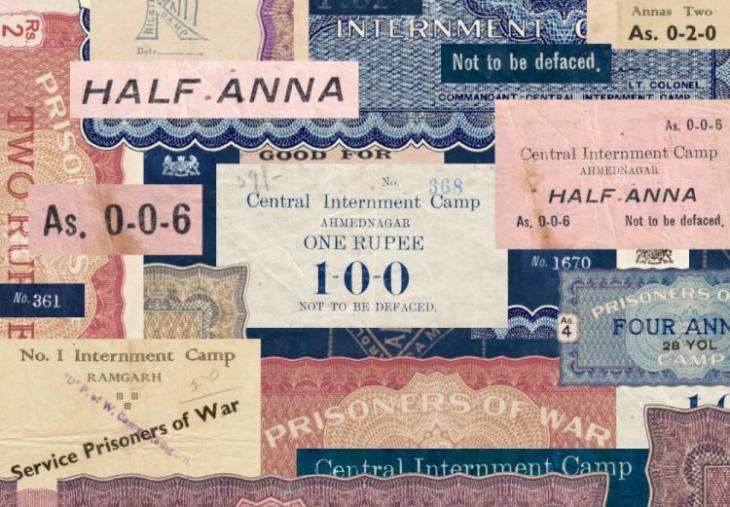

The British provided the internees with necessities, and also took charge of their personal funds. The British would pay out additional sums to internees, offering to sell land or jewellery on their behalf, if more money was desired to pay for further items in the camp, such as extra lamps or food. Some money was also paid out of the assets of their employers, which had been requisitioned, although there was some debate between the Government of India and the Foreign Office over how much money the British were allowed to take out of the companies under the Hague Convention on using enemy property. This led to investigations into the finances of their employers to see whether, as the internees of Wönckhaus claimed, the employees had a private credit balance with the company, and were therefore entitled to company money.

![Red Cross card of Carl Eisenhut, one of Wönckhaus’s employees. Image courtesy of ICRC archives [ACICR C G1]](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/c_g1_f_12_01_0022_0368_0.jpg?itok=U5vXVSvy)

The Trading with the Enemy Amendment Act (1916) led to further complications for the British, as it required that enemy assets should be liquidated and the sale proceeds held in trust. Percy Cox, Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , wanted to confiscate the assets of Wönckhaus, because he felt there was evidence that ‘their branches in Persian ports of the Gulf were used to finance the German missions of piracy and murder directed against us [Britain] in Persia, in which more than one of their staff have personally played an active part’ (IOR/L/PS/10/565, f. 115r). However, this was rejected by the Foreign Office.

Commercial interests

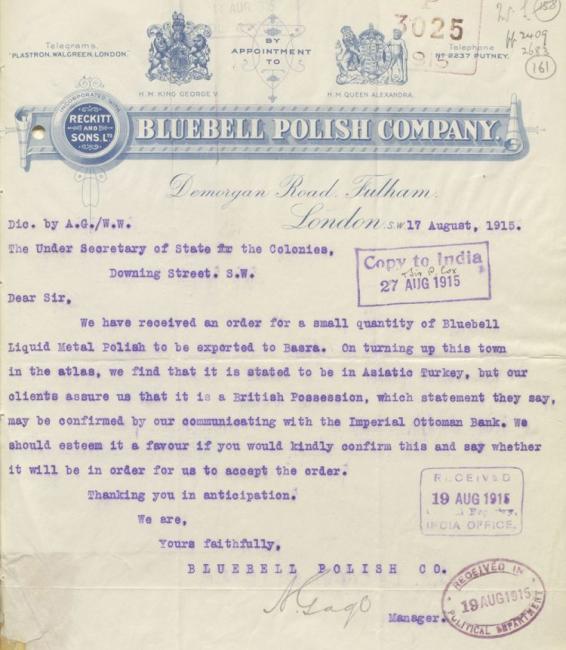

Communication was also vital for companies that dealt with the Ottoman-controlled areas. Business dealings with enemy-occupied territory were prohibited, but it could be difficult to discern where to draw the line. Gulbenkian Brothers and Co., based in London, wrote via their solicitors to the Secretary of State for Home Affairs on 24 February 1915 to ask whether it was permissible to trade with Basra, and wanted written assurance that the town was in British hands before committing themselves (IOR/L/PS/10/565, f. 240r). They were reassured by Ralph Paget, Assistant Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, that their trade could continue. Similarly, the Bluebell Polish Company of London had received an order for Basra and looked up the location on the atlas; on discovering that it was in Asiatic Turkey, they wanted confirmation from the Under Secretary of State for the Colonies before proceeding.

One particularly difficult case involved a British ship, the SS Amatonga, owned by the Ellerman and Bucknall Steamship Company, which set sail for Basra before war had been declared. She was delayed by British officials at Bushehr, resulting in her arrival at Basra after war had broken out, and as a result her cargo was either looted or burnt. The British regretfully decided that they would have to postpone seeking compensation until after the end of the War, when (they hoped) the cost of the cargo could be extracted from the Ottomans.

Evidently, managing a country, let alone a global empire, during wartime involved much more than dealing with the military. The India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. had the difficult task of coordinating action across the diverse regions of East Africa, Zanzibar, and the Gulf.