Overview

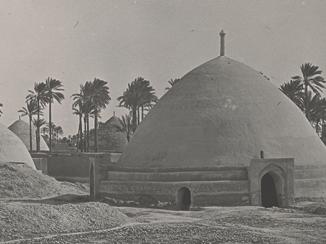

Early cemeteries in the Gulf

Early British burials in Persia usually took place in Armenian Orthodox cemeteries. The earliest known British grave in Persia is that of William Bell, the East India Company Factor at Isfahan, who was buried in the Armenian cemetery of New Julfa in 1624. However, British burial grounds were quickly established in the region, earlier than in some parts of Catholic Europe in many cases. By the 1760s, there were already European burial grounds around the Gulf, including at Mocha and Bandar Abbas, but unofficial individual burials continued in places where there were no established cemeteries.

Establishment

In 1825, the British Government attempted to regulate burial grounds in the Gulf region by obliging consuls to establish them for local British communities. Formally establishing a cemetery indicated the British intention for their presence in the region to be long-lived. These cemeteries were conceived as secular, and were linked more clearly to a British or European identity, rather than to a religious affiliation. Christians of any denomination as well as non-Christians could be buried there. Unlike cemeteries in England, these spaces were normally located outside cities, and were not connected to churches and parishes.

Most cemeteries were established on land granted free by the local ruler, but the East India Company might also request a burial ground when setting up a Factory An East India Company trading post. . When a Factory An East India Company trading post. was founded at Basra in 1763, the Shaikh of Bushehr paid for a garden and burial ground. Isolated burials still occurred for a long time, of individuals such as members of the Indo-European Telegraph Department, who died while constructing the telegraph line, and were buried where they died.

By the late nineteenth century, with the arrival of missionary societies in the Gulf, the secular nature of British cemeteries abroad had begun to change. Cemeteries which had initially been secular were consecrated, making them more explicitly Christian sites. However, the cemeteries which the Church Missionary Society of London and the American Arabian Mission established at Isfahan, Kerman, Shiraz, Tehran, Yazd, and Hamadan were still ecumenical, as the religious divisions which persisted in Europe seem to have been less overt in the Gulf. For instance, when Andrew Jukes died at Isfahan in 1821, he was buried in All Saviour Cathedral, the Armenian Church. His companion read the Anglican Burial Service over his grave after the Armenian Orthodox service.

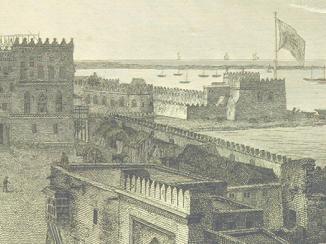

Division on national lines

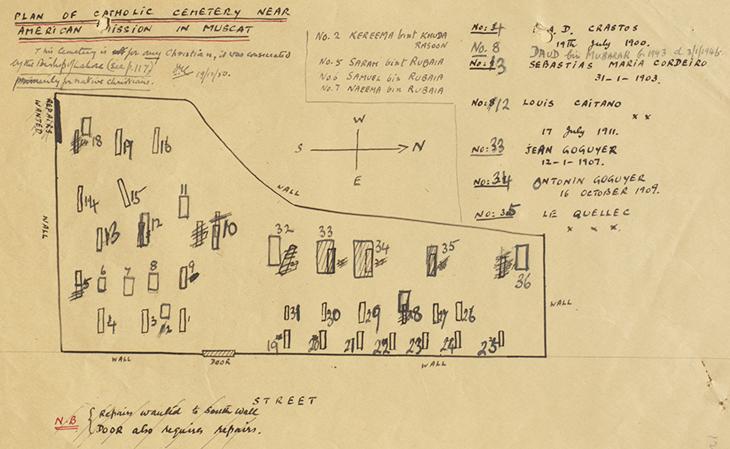

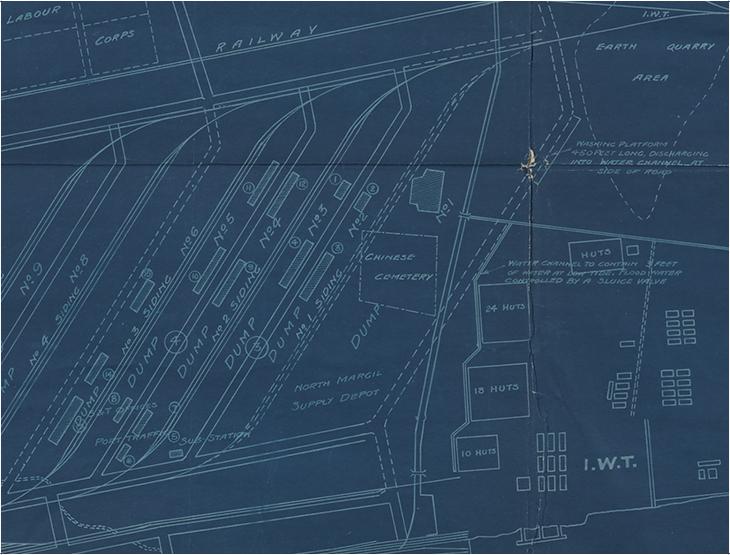

Sometimes specific groups had their own burial grounds, such as the Chinese Labour Corps at Al Ma’qil, which had a Chinese cemetery in 1917. However, grants of land to the ‘European community’, as at Muscat, led to problems when more non-European Christians arrived in the Gulf (IOR/R/15/6/454, f. 10r). At the British cemetery in Baghdad, it took part of the wall collapsing in the floods of 1906-1907 for an extension to be built, thereby allowing for non-European Protestants to be buried there, whereas previously it had been exclusively for Europeans.

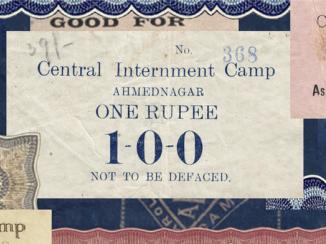

Funding

Local British communities would attempt to raise money in subscriptions for the general upkeep of cemeteries, but also resorted to the British Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , or the Government of India for larger items of expenditure. When the missions arrived in the Gulf, they also contributed to basic costs, but frequently had to ask the British Government for money. After 1888, the British Government directed that grants to civil cemeteries should cease, but payments continued in places that lacked a substantial number of British residents.

These places continually struggled for money, and often sought private funds. In 1931, the cemetery at Kuwait was in such a bad state that burials had to take place in Basra instead. A collection from firms with employees buried there, and a newspaper appeal in Britain did not yield enough to repair it. The Kuwait cemetery had only been established in 1913, while previous burials had taken place in the Political Agency’s camel compound. Even when the community at Jeddah had enough money to improve the cemetery, they decided that such works would risk making it a target for vandalism.

Areas of tension

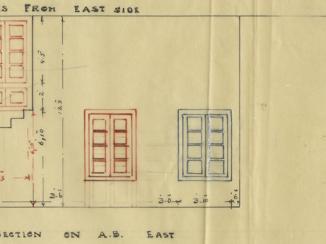

Cemeteries were frequently the focus of vandals, sometimes prompting graves to be moved in order to protect them. In some instances, gravestones were stolen. In 1942, the British Consul at Muscat requested the return of a headstone of a man who had died in 1911, which was found forming part of the floor in a Mullah’s house. Between 1934 and 1939, twenty English-inscribed gravestones disappeared from the old Armenian Cemetery in Shiraz. When two more went missing within a fortnight, the British Consul ordered the remaining three to be moved to the new British cemetery, which was enclosed behind a gate.

A change in circumstances could lead to new tensions. The Akbarabad Protestant Cemetery was founded in the late nineteenth century at an isolated village, but as Tehran grew the village became a suburb. By the 1960s, the cemetery was forced to relocate, as the inhabitants objected to the presence of a cemetery so close to their houses. Christian burials were not the only points of contention, however. When British officials were enquiring about establishing a Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. at Aden, the Sultan’s refusal to allow Hindus to cremate their dead was also a problem.

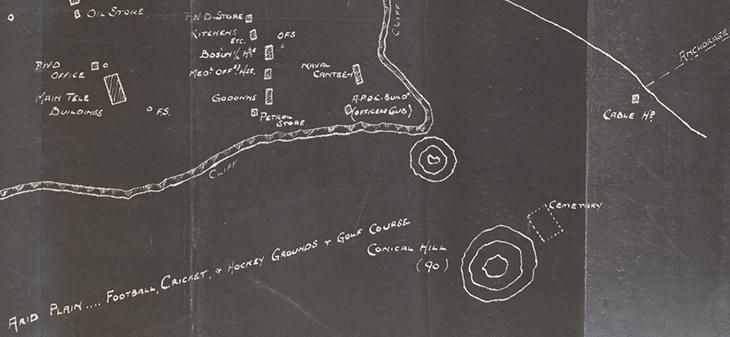

When Basaidu and Henjam naval bases were handed over to Iran in 1935, Britain stipulated that Iran continue to respect both cemeteries and allow access to repair the graves. An inscription in Basaidu cemetery, reading ‘British Basidu’ became a point of conflict, as Iranian officials wanted to erase it, and the British Consul objected.

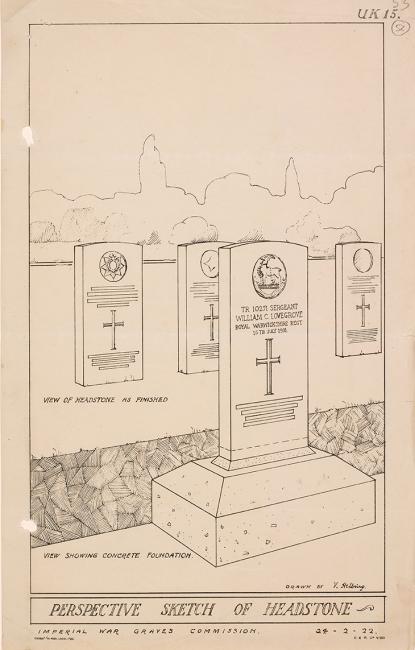

The Imperial War Graves Commission

The Imperial War Graves Commission was set up in the First World War to care for the graves of servicemen. The Commission intended for war graves to be consolidated in one place to make it easy to look after them. However, the graves in the Gulf were widely scattered, and often located in cemeteries that were otherwise civilian. Although bodies were frequently moved to designated war cemeteries, some remained in situ in civilian cemeteries. Among these were two in Muscat, for which the War Graves Commission shipped two headstones in 1926. The Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. was responsible for the transport and erection of the stones, but the Commission paid for them. Oil companies also made their own arrangements for the dead, commonly repatriating their bodies or ashes, made easier by the Bahrain Petroleum Company (BAPCO) having its own crematorium at Awali.

The importance of graves

In considering the political elements of these debates, it is easy to forget the importance of graves to the families of buried individuals. The documents on the QDL record a widow asking for a photograph of her husband’s grave at Muscat, parents paying every year to water flowers on their son’s grave, and a detailed description of an infant daughter’s grave at Kerman. Although they were often separated by a great distance, families clearly remained attached to the graves of their relatives in the Gulf.