Overview

In the nineteenth century, British agents and residents in the Gulf became increasingly involved in recovering goods from shipwrecks and obtaining compensation for lost cargoes. This could be a complex operation, beginning with determining the circumstances of the shipwreck, and concluding with negotiations between local inhabitants, governors, insurers, and ship owners.

Insurance

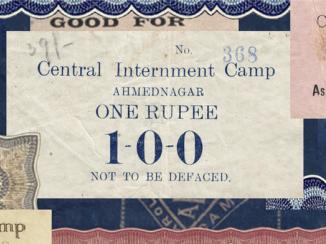

The maritime insurance industry in India developed rapidly as trade between India and the Gulf expanded. This system relied on individual underwriters, who were themselves usually merchants, pooling their resources. They would reimburse the owners if the cargo was lost, in exchange for a fee paid in advance. Most cargoes transported from India to the Gulf were at least partially insured, meaning that any losses suffered in a shipwreck would have been of concern to more than just the owners. Even sharing the risks, individual underwriters could potentially lose considerable amounts of money.

The Law of Salvage

As is the case today, those who rescued ships in distress were entitled to a reward, often a proportion of the cargo that they had helped to salvage. However, these agreements were not formally set down, and varied from one place to another. Traditional customs in certain parts of the Gulf dictated that any property landed on the shore belonged to the local inhabitants. The British, however, attempted to alter these customs through a series of treaties.

Treaties

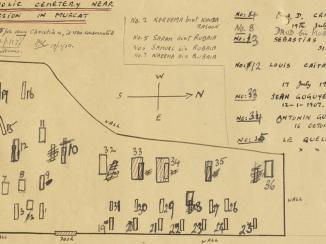

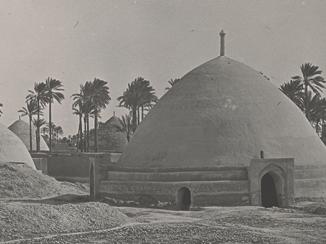

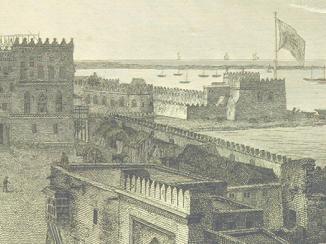

Two of the earliest British treaties that mention shipwrecks were made in 1763 with Karim Khan Zand, the Vakil Elected representative or attorney, acting in legal matters such as contracting marriage, inheritance, or business; a high-ranking legal official; could also refer to a custodian or administrator. of Persia, and Shaikh Sa‘dun Al Madhkur of Bushire [Bushehr]. Both stipulated that if any English vessel was driven ashore or wrecked on their coasts, the shaikh or governor of the adjacent regions would not plunder or claim any part of it, but would do everything possible to save the vessel and its cargo. Similar treaties were made with the rulers of Socotra, Aden, and Muscat between 1798 and 1876. These treaties were meant to safeguard vessels sailing under British colours, their sailors, and their cargo, but their application was not always straightforward.

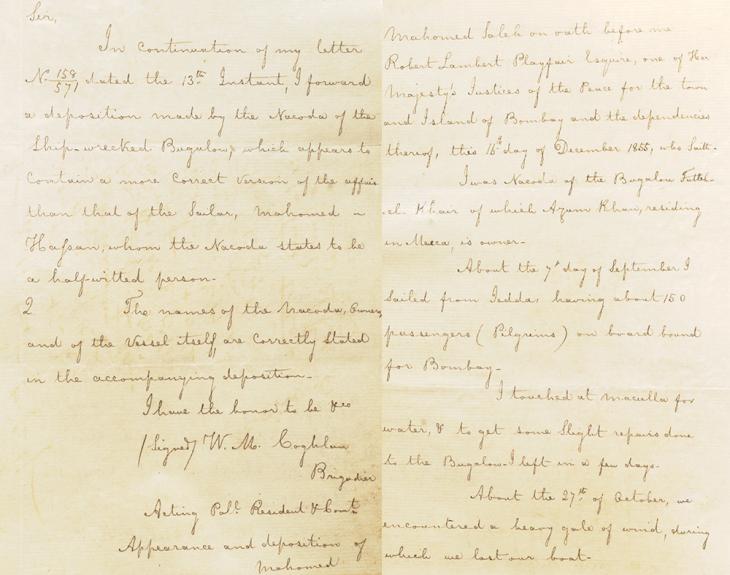

Multiple accounts

What happened after a ship was wrecked varied. It was often the job of the nearby Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. or Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. to determine the facts about the wreck, which was not always an easy task. In 1855, a boat carrying pilgrims was wrecked near Ras el Had [Raʾs al-Ḥadd, Oman]. The initial account by a sailor, Mahomed bin Hassan, claims that the boat was called the El Hamra, and was sailing under Arab colours. It goes on to say that when she was wrecked, around 200 Bedouins went on board, plundered the ship, stripped the passengers, killed three men, and enslaved a number of other passengers. However, a later account by the nakhuda, Mahomed Saleh, who describes Mahomed bin Hassan as ‘a half-witted person’, states that the boat was actually called the Futteh el Khair [Fatḥ al-Khayr], was sailing under the British flag, and was indeed plundered, but that no one had been killed or enslaved.

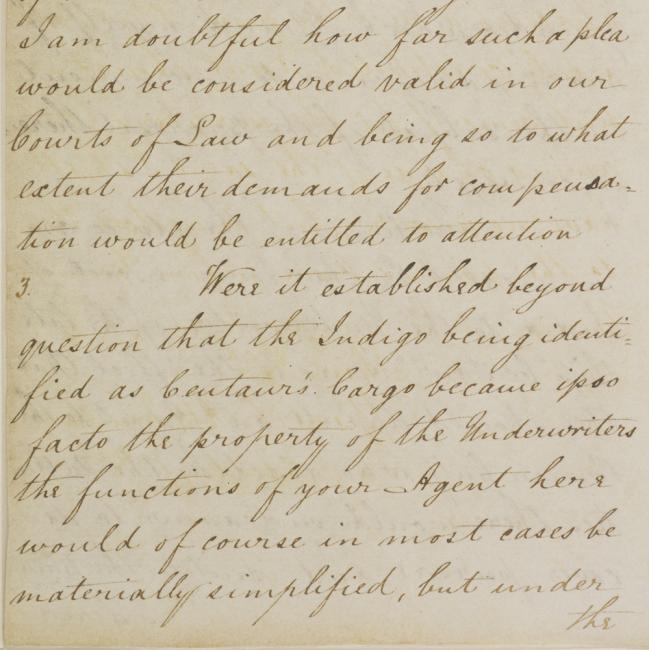

Recovering the cargo or its equivalent cost, in accordance with the treaties, was frequently one of the Agent’s or Resident’s duties. When the Centaur was wrecked in 1852, and her goods plundered, the underwriters appealed to the British Resident to recover the cargo. This consisted mostly of indigo, and they assured him it would be easy to find, as the Centaur had been carrying the whole supply of indigo to the Gulf for the entire season. Although he managed to retrieve some, the Resident, Captain Arnold Kemball, found it troublesome to recover the cargo, particularly from merchants who were unaware of its origin. Moreover, the legal position taken for the recovery was somewhat tenuous, as the merchants who were in possession of the indigo had bought it, and therefore might be entitled to compensation.

Assistance from the shore

However, the loss of cargo and/or personal effects was not inevitable; there were also instances where local governors provided aid to shipwrecked crews, and were subsequently rewarded by the British. When the Firoze ran aground, the Shaikh of Kuwait, Shaikh Jābir I al-Ṣabāḥ, sent six boats to help her refloat, and was in turn presented with gifts totalling 800 rupees Indian silver coin also widely used in the Persian Gulf. . Similarly, the Imam of Muscat allowed the crew of the Sir James Cockburn to sail back to Mauritius in one of the Imam’s own ships, dropping off some crewmembers at the Seychelles.

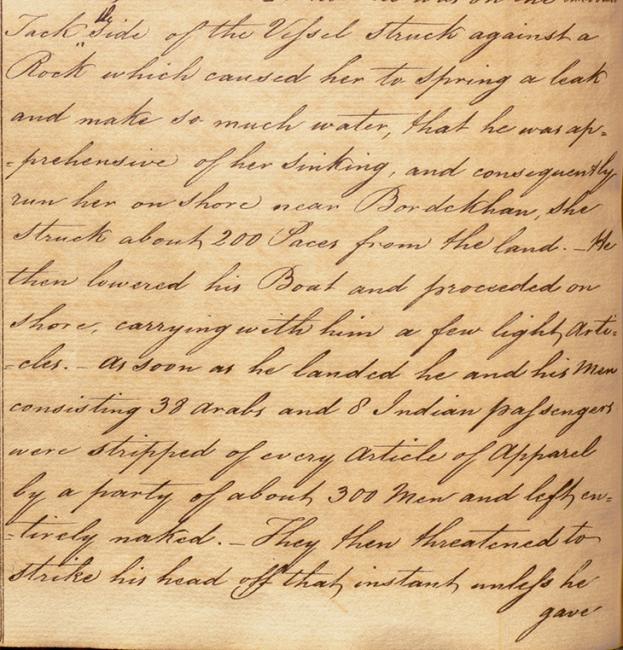

Local people were sometimes aware that the British government took a firm line against plundering British ships. In 1826, a crew reported that when their ship Budree [Badrī] was wrecked on the Dashti coast of Persia, the inhabitants took their cargo and stripped them naked. They were then forced to sign a document stating that they had not been plundered, but had lost all of their cargo in the wreck, and had suffered ‘not the slightest injury or inconvenience from the hands of the Inhabitants’ (IOR/R/15/1/36, f. 91r). The British envoy to Persia, Colonel John Macdonald Kinneir, asked the Persian government to compensate the cargo owners. Muhammad Zaki Khan Nuri, Vazir of Fars, initially refused, citing the custom of the country, and argued that the treaty with the British had been cancelled. Eventually he agreed to reimburse part of the cost of the cargo.

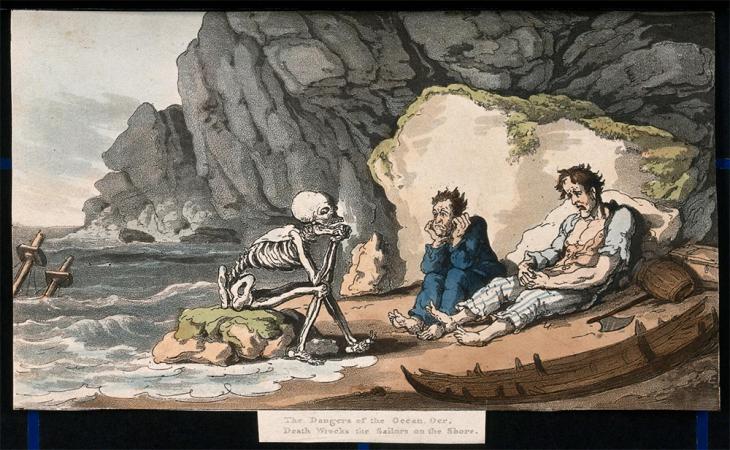

Preferable to Drowning

Outcomes for shipwrecked crews were generally good; the files hold no confirmed cases of crews being murdered, and the value of goods could usually be recovered either from the local shaikh or governor, or from the insurers. The sailors knew the risks of running aground, but these were often preferable to the dangers of sinking in open water.