Overview

Perhaps surprisingly, two legal systems operating in the Gulf in the early twentieth century seem largely to have worked together in harmony. On the one hand, sharia, influenced by local custom applied to local people and was administered by the local sheikhs; on the other, British subjects and foreigners were subject to British jurisdiction. But in applying their own judicial systems to the Gulf, the British had to be careful not to offend existing Arab customs, which themselves were diverse. This potential clash of cultures occasionally resulted in difficulties with local rulers.

Khidma

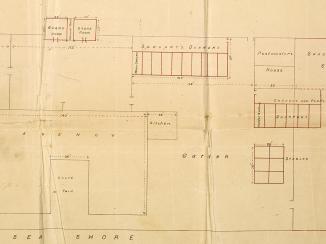

One such issue concerned Khidma (lit. ‘service’). Khidma was the customary payment by the British Political Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. to the Shaikh of Bahrain or his officials of ten percent of all amounts paid into the Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. Court in civil suits and bankruptcy proceedings. The Shaikh then used this money to remunerate local emirs. The khidma was paid not only when one of the parties in a suit was a subject of the Shaikh, but even when both were British subjects or foreigners. No khidma was due in cases that were settled amicably.

In 1915, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain, Terence Humphrey Keyes, warned against the introduction under the Bahrain Order in Council A regulation issued by the sovereign of the United Kingdom on the advice of the Privy Council. of a regular and inelastic scale of fees for instituting any civil suit, something which he considered would be ‘foreign to Arab ideas of justice’. The Agent suggested instead a revised scale of fees for British and foreign cases: in return Shaikh ‘Īsá bin ‘Alī Āl Khalīfah of Bahrain was to be compensated to the tune of three hundred rupees Indian silver coin also widely used in the Persian Gulf. a month. The Khidma system was to remain in place on cases involving Bahrain subjects, in order to avoid upsetting local custom.

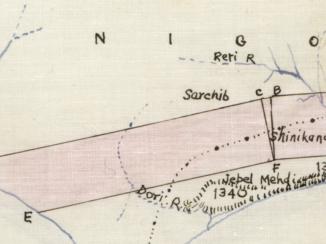

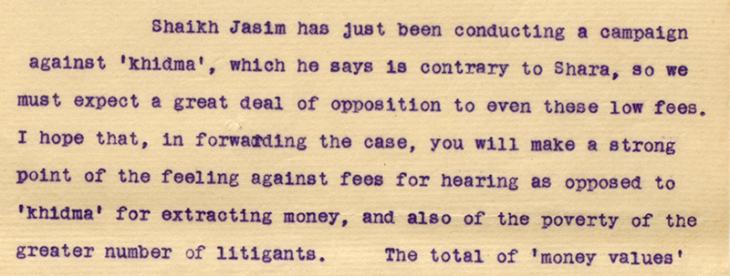

Still, Keyes was worried that the suggested low fees would encounter resistance from the Foreign Department, the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. , Foreign Office and Treasury – especially the latter, which he describes as an ‘abode of avarice’. Moreover, the Shaikh of Qatar, Shaikh ‘Abdullāh bin Jāsim Āl Thānī, had been conducting a campaign against khidma on the grounds that it was against his interpretation of sharia, meaning the British could expect opposition to even the new low fees.

Still, Keyes was worried that the suggested low fees would encounter resistance from the Foreign Department, the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. , Foreign Office and Treasury – especially the latter, which he describes as an ‘abode of avarice’. Moreover, the Shaikh of Qatar, Shaikh ‘Abdullāh bin Jāsim Āl Thānī, had been conducting a campaign against khidma on the grounds that it was against his interpretation of sharia, meaning the British could expect opposition to even the new low fees.

In the event, the Shaikh of Bahrain turned down the proposed payment of three hundred rupees Indian silver coin also widely used in the Persian Gulf. per month, for fear of his being thought by Arab rulers to be a subsidised vassal of Britain. Eventually, in 1919, he agreed to the total abandonment of the payment of khidma in cases involving British subjects and foreigners and accepted the terms of the Order in Council A regulation issued by the sovereign of the United Kingdom on the advice of the Privy Council. .

The Pragmatic British Approach

India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. records indicate that such controversies were infrequent. Detailed correspondence between officials in London, India and the Gulf shows that the British carefully discussed the introduction of Orders in Council A regulation issued by the sovereign of the United Kingdom on the advice of the Privy Council. and King’s Regulations (a collection of regulations used as guidance for officers in discipline and personal conduct), and used existing Orders as models for new legislation. Far from seeking to impose Western judicial systems, the British were often at pains to extend local customs to persons under their direct control.

Co-operative Justice

Thus in Muscat in 1920, the British altered the existing Order in Council A regulation issued by the sovereign of the United Kingdom on the advice of the Privy Council. to extend local regulations to British subjects (mostly British Indians) in order to curtail arms infringements. They did so again in 1935 to improve municipal sanitation in Muscat and Muttrah. In terms of their own courts the files show that British officials exercised justice over British subjects and foreigners in a conscientious and even-handed way.

The British adapted their extra-territorial jurisdiction as need arose, and respected local customs. Legal historian Husain Al Baharna calls the relationship between local institutions and British courts a co-operative one. Where problems arose with local rulers and between neighbouring states, experienced British officials like Keyes discussed the issues carefully and came up with sensitive diplomatic solutions.