Overview

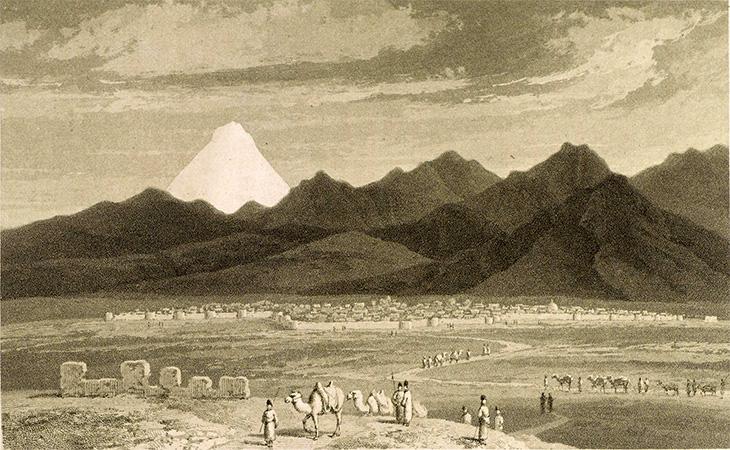

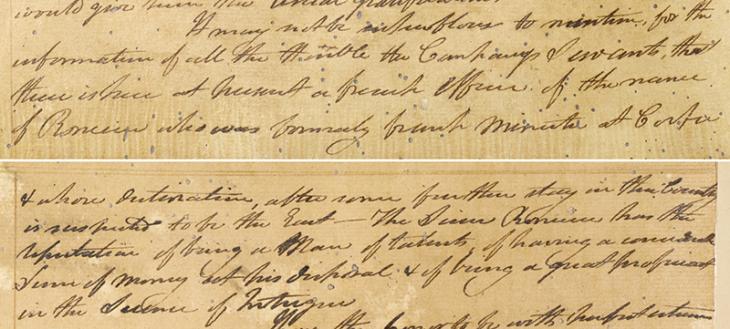

On 27 September 1805, a boat came into the harbour at Bushire bearing a packet of letters for William Bruce, the Honourable East India Company’s Acting Resident there. The packet contained dispatches from Harford Jones, the Company’s representative at Baghdad. In them, Jones warned Bruce to be particularly on his guard against the appearance in any of the Gulf ports of a French officer by the name of Romieu. He enclosed copies of letters he had received from other British officials in the east relating to the Frenchman’s activities.

Proficient in the Science of Intrigue

The first of these was from Alexander Stratton, the British Minister Plenipotentiary to the Ottoman Porte (a diplomat invested with full powers to represent Britain at the Ottoman Court), who warned in June 1805 that Romieu, formerly French Minister at Corfu, was in Constantinople, adding that he had ‘the reputation of being a man of talents, of having a considerable sum of money at his disposal, and of being a great proficient in the science of intrigue’.

The next letter to Jones had come from John Barker, Consul of the Levant A geographical area corresponding to the region around the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Company (a British chartered company that regulated trade with Turkey and the eastern Mediterranean), who wrote from Antioch (Antakya) in July 1805 that Romieu had now arrived there with the probable intention of making his way to India, or at least Persia. Later in July, Barker warned Jones that he felt certain that Romieu was on his way to Baghdad as the Frenchman had changed considerable sums of money at Aleppo into the gold currency most commonly used at Baghdad.

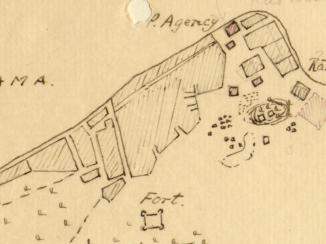

Jones concluded his dispatches with a further letter to Bruce, in which he gives a description of Romieu: ‘His person is of the middling size, that is about 5 feet 8 or 9, without any prominent feature of countenance, his complexion and hair dark, his age about 36, his habit rather spare than otherwise, and when he speaks a slight lisp in his speech is discernible’. He was attended by an interpreter and two persons who were apparently servants. Jones thought it was extremely important to put Bruce on his guard in case the Frenchman tried to make his way to Muscat or India. In response Bruce undertook to keep a watch on the southern ports of the Gulf and alert his own agents at Shiraz and Isfahan.

Military Alliance between France and Persia

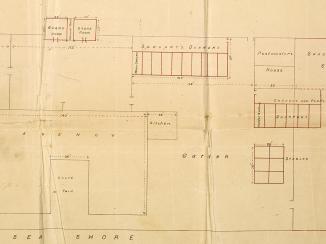

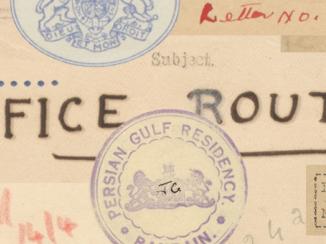

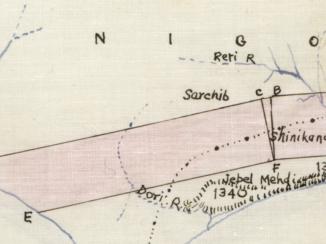

The correspondence concerning Romieu, whose activities resemble those of one of John Buchan’s shadowy foreign agents from a century later, is contained in the Bushire Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. diary for 1805–06.

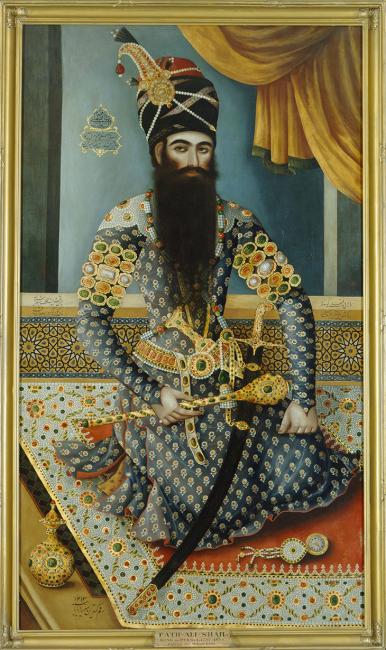

Lieutenant-Colonel Alexandre Romieu was indeed acting as an emissary of Napoleon, one of two envoys at the time whose intention it was to explore the possibility of a military alliance between France and the court of Persia. The Shah, Fat’h Ali Shah Qajar, and his government were keen to use French power as a counterweight to that of Russia and Britain in the region, and Napoleon still entertained the dream of conquering India. The Shah’s heir, Abbas Mirza, was deeply impressed by Napoleon’s victory over the Russians and Austrians at Austerlitz in December 1805. Although a treaty between France and Persia was eventually signed in 1807, the Peace of Tilsit soon after that ended hostilities between France and Russia, and as a result the Franco-Persian alliance never became active.

Rumours of Poison

However, Romieu’s mission to Persia was short-lived. The writer The lowest of the four classes into which East India Company civil servants were divided. A Writer’s duties originally consisted mostly of copying documents and book-keeping. and diplomat Iradj Amini recounts the story of how Romieu survived an assassination attempt while at Aleppo, fomented – according to one source – by John Barker.

By the end of September he was in Tehran, but succumbed to illness while in the Persian capital, and died on 12 October, after ‘constantly vomiting for three days and suffering from shivers and great heat’. Romieu is buried in a suburb of Tehran ‘next to the mausoleum of one of the venerable figures of Shi’ite Islam’. A French source reported that the local rumour was that Romieu had been poisoned: his interpreter also sickened but survived and eventually returned to France.

Amini deepens the picture of Romieu that emerges from the records by crediting him with diplomatic skills and strategic insight. He praises Romieu’s analysis of political attitudes in Tehran and claims that Romieu believed the Persians’ greatest potential for assistance to France was against the Russians, not the British, as they wholly lacked a navy.

The correspondence regarding Romieu not only illustrates the wider significance of the Persian court’s attempts to manoeuvre for advantage between the great European powers, but also demonstrates the way in which Britain’s representatives in the East exchanged information in the face of a serious threat to security in the region.