Overview

It may have appeared like just another instance of gunboat diplomacy, but contemporary records show that the British authorities were not amused by the handling of a naval bombardment in 1910 that became known as the Dubai Incident.

Illegal Arms and Punitive Terms

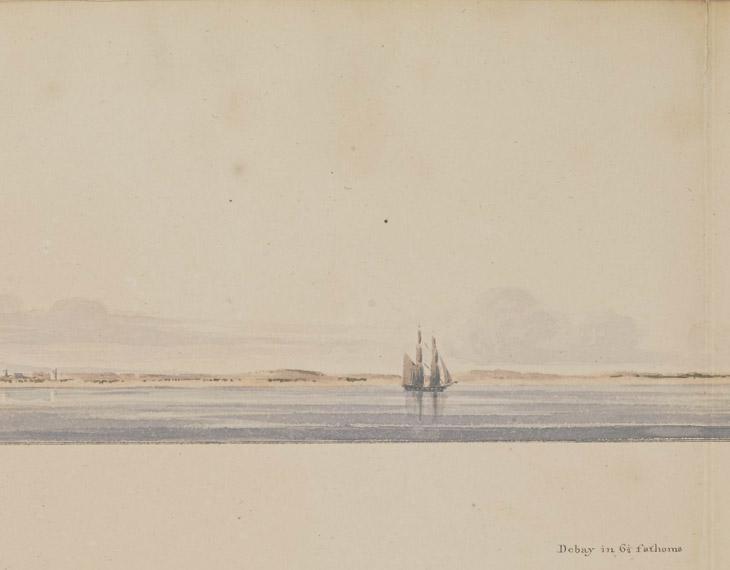

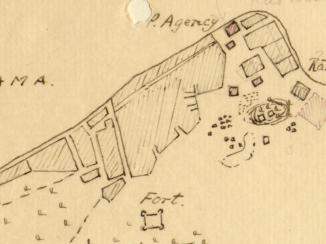

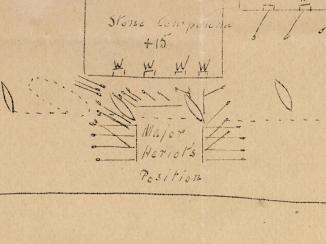

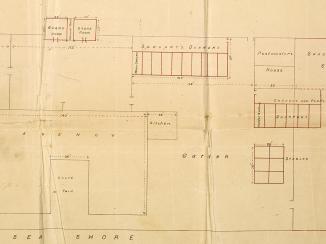

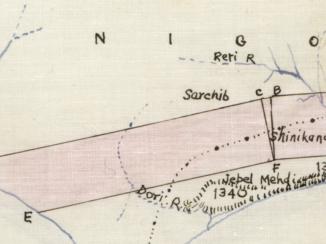

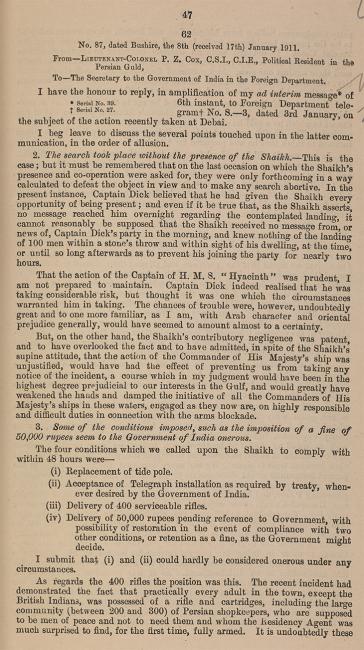

What should have been a straightforward operation to investigate reports of a cache of illegal arms at Dubai ended in a gun battle, naval bombardment and numerous deaths. Following the incident, the senior British officials in the area, Lieutenant-Colonel Percy Cox, Resident in the Gulf, and Rear-Admiral Sir Edmond Slade, Commander in Chief, East Indies Station, moved quickly to impose punitive demands on the Shaikh of Dubai. These included the handing over of four hundred rifles, the establishment of a British telegraph station on his land, payment of a fine of 50,000 rupees Indian silver coin also widely used in the Persian Gulf. , and the acceptance in Dubai of a British Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. and his military guard.

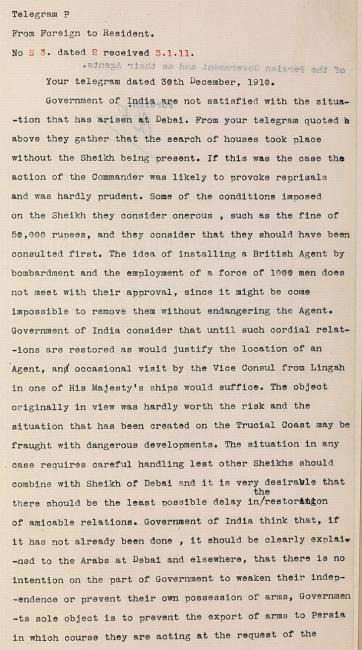

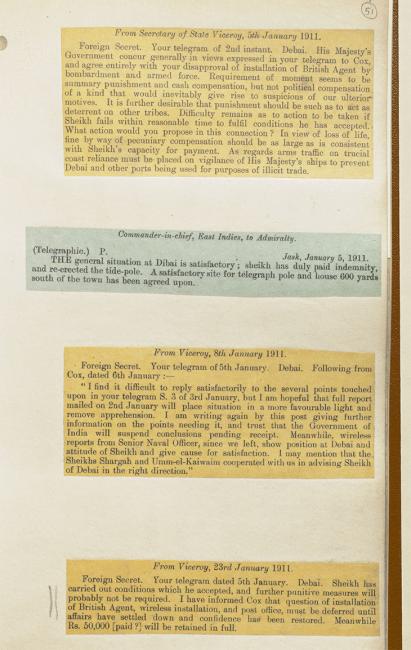

However, the Government of India was not satisfied with what had taken place at Dubai. In a telegram to Cox dated 2 January 1911, the Government declared that the decision of the commander of the landing party to press on with the search, despite the fact that the Shaikh was not present ‘was likely to provoke reprisals and was hardly prudent’. The Government was also not satisfied with the conditions imposed on the Shaikh, which they described as ‘onerous’, adding that they should have been consulted first about the fine of 50,000 rupees Indian silver coin also widely used in the Persian Gulf. .

Damaged Relations

The telegram continued: ‘The idea of installing a British Agent by bombardment and the employment of a force of 1000 men does not meet with their approval, since it might become impossible to remove them without endangering the Agent’. The Government of India was also concerned about the damage done to relations with other rulers in the area:

The object originally in view was hardly worth the risk and the situation that has been created on the Trucial Coast A name used by Britain from the nineteenth century to 1971 to refer to the present-day United Arab Emirates. may be fraught with dangerous developments. The situation in any case requires careful handling lest other Sheikhs should combine with the Sheikh of Debai [Dubai] and it is very desirable that there should be the least possible delay in the restoration of amicable relations.

The telegram ends by stating that it needed to be clearly explained to the Arabs at Dubai and elsewhere that the Government of India did not wish to weaken the independence of the peoples of the Trucial Coast A name used by Britain from the nineteenth century to 1971 to refer to the present-day United Arab Emirates. or prevent their own possession of arms; but rather prevent the export of arms to Persia – in accordance with the wishes of the Persian Government.

Difference of Opinions

Cox defended his actions in a letter to the Government of India dated 8 January 1911, saying that he did not think the conditions imposed on the Shaikh were onerous, or that a dangerous situation had been created on the Trucial Coast A name used by Britain from the nineteenth century to 1971 to refer to the present-day United Arab Emirates. : the Shaikhs of Sharjah and Umm al Qaywayn had cooperated, and wireless reports from the area showed that the position was ‘quite satisfactory’. However, the Government of India refused to alter its basic assessment of the incident.

The British Home Government was in agreement with the views of the Government of India. A telegram from the Secretary of State to the Viceroy dated 5 January 1911 stated that ‘His Majesty’s Government concur generally in views expressed in your telegram to Cox, and agree entirely with your disapproval of installation of British Agent by bombardment and force’.

Caution

The British were keen that there should be no repeat of the incident. Rear-Admiral Slade was careful, in a memorandum of August 1911 to British naval commanders in the Gulf, to warn that extreme caution should in future be used in all operations on shore concerned with the suppression of arms traffic.

The papers show that the Dubai Incident was not simply an incompetently-managed policing operation, since the Government of India realised immediately that serious mistakes had been made and were keen to limit the potential damage to Britain’s reputation among her allies in the Gulf. In a region bound to Britain by treaty obligations, rather than under direct rule, and where there was competition from other European powers, the British wished wherever possible to avoid the overt use of force. The events of the Dubai Incident had clearly violated this important principle.