Overview

In 1929, the British Agent in Gwadar (Gwadur) – a port on the Arabian Sea coast of Baluchistan – was one M. Waris Ali. Although in his role as ‘Native Agent’ Waris Ali produced reports that were forwarded to Bushire, when communal riots broke out his British superiors were divided on whether to believe his account of events.

Vivid Impressions of Gwadar

In his Annual Report for 1928, Waris Ali gave a full description of Gwadar, including references to the continuing slave trade in the area as well as to the important local fish trade and agriculture:

Right up the hills of strange structure situated in the vicinity of Gwadur town, there is a valley [that] with the assistance of rain water accumulated in what is generally known as “Portuguese Tank” yields very satisfactory crops of all types in profuse abundance.

Waris Ali also provided a vivid account of the arrival of steamers:

BISN Coy’s [the British India Steam Navigation Company’s] steamers anchor at a distance of about 6 miles from the beach and therefore many are the difficulties that have to be surmounted when passengers get on board or get down the steamer or when transhipment between steamers and dhows takes place.

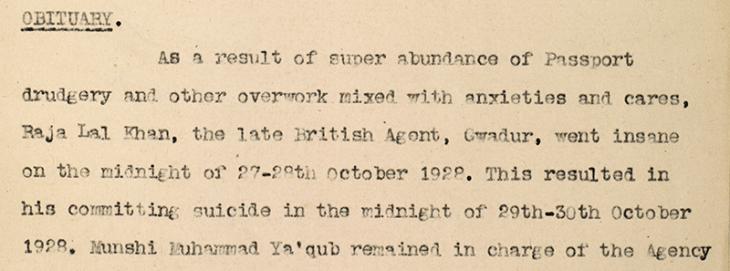

Clearly Waris Ali was a novelist in the making. He concluded the report with an obituary for Raja King Lal Khan, a preceding Agent who ‘as a result of super abundance of Passport drudgery and other overwork mixed with anxieties and cares [. . .] went insane on the midnight of 27–28th October 1928. This resulted in his committing suicide in the midnight of 29th–30th October 1928’.

Riots

His superiors were not amused, however, when it came to the way Waris Ali relayed news of the communal disturbances that took place at Gwadar in 1929 between Khojas and Baluchis. The former were Ismaili Shia Muslims, also referred to as ‘Aga Khanis’, who were British subjects while the latter were subjects of the Sultan of Muscat. The troubles started with allegations that a mosque had been defiled by Khojas; in the disturbances that followed, a member of the Khoja community, Khimji Reinoo, was killed and a Khoja graveyard desecrated.

Waris Ali described the events in a series of reports and telegrams to the British authorities. His superiors, while taking the unrest seriously, were unimpressed by his description of events. The Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. at Bushire, Lieutenant-Colonel Cyril Charles Johnson Barrett, refers to his ‘absurd telegrams’, which showed that he ‘rather lost his head’. Major Gerald Patrick Murphy, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. at Muscat, resented Waris Ali’s ending his letters to him by referring to an unidentified individual with the words ‘Love to Patrick’.

Economic Troubles?

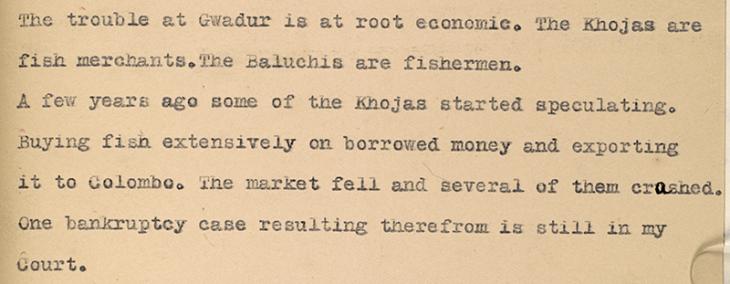

The British thought the trouble at Gwadar was basically economic: the Khojas were fish merchants, the Baluchis fishermen and the unrest followed attempts by the merchants to buy catches at unfair prices. As the communal troubles continued, a further member of the Khoja community, Ghulam Ali, was killed in 1931. By July of that year, Khojas in Gwadar were leading the life of a ‘beleaguered garrison’, forced to live inside the precincts of the fort there, for fear of being ‘murdered or otherwise molested by the Baluchis’.

British officials tried to play down intercommunal differences as the root cause of the troubles: there was no evidence that Ghulam Ali had been killed by Baluchis, and the Khojas – who had given no assistance to the Muscat state authorities and the British representative –-– appeared to have something to hide.

An ‘Indian Gentleman’

Waris Ali had already been replaced as Agent by this time, but one British official tried to pin the blame on him: ‘It is a pity that a man of the type of Lal Khan was not obtained as British Agent, as it was mostly due to him that no communal troubles occurred in Gwadar for so many years’. The circumstances of Lal Khan’s death show how demanding an Agent’s routine workload could be.

Despite others’ criticism, Waris Ali was praised by one British official at Karachi, de Smidt. According to de Smidt, he knew Arabic and Persian well; his work was ‘distinctly good,’ and the other British representative, Murphy, had underestimated the seriousness of the incidents taking place in the town. Furthermore, continued de Smidt: Waris Ali was not a clerk, but, in his own estimation, an ‘Indian gentleman’.

By 1932 the Khojas and Baluchis ‘had largely composed their differences’. Waris Ali’s role in reporting the unrest provides a colourful picture of the events as well as the man himself. Although he had his critics as well as his supporters, his conscientious and enthusiastic approach to his duties illustrates the continuing importance of the long tradition of British so-called Native Agents Non-British agents affiliated with the British Government. .