Overview

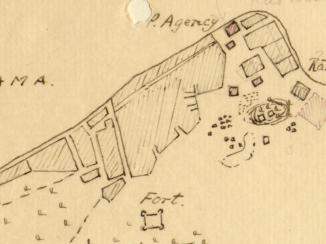

Pearl fishing was for centuries the main industry in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. region. Until comparatively recent times the trade was carried on by divers manually gathering the oysters from the sea bed.

The British authorities in Bahrain were interested in collecting information on pearling in order to further British and local economic interests, as demonstrated by a file they maintained on the trade covering the years 1929–35 which reflects how the pearling industry was viewed in official reports and the contemporary press.

Fathoms below the Surface

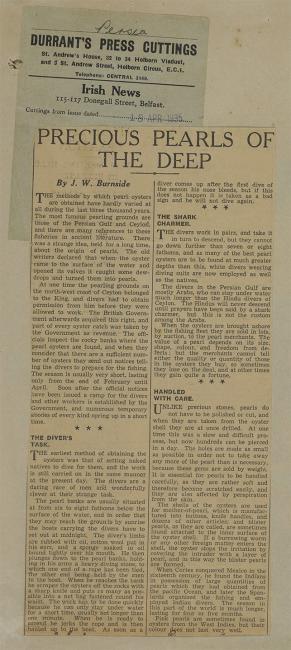

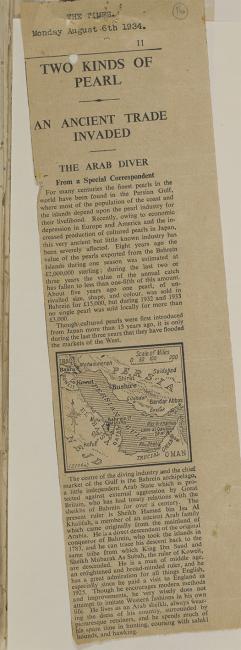

The divers who recovered pearl oysters from the bottom of the sea had to be able to dive to depths of up to eight fathoms (over fourteen metres), according to an article contained within the file from the Irish News, published in April 1935.

Of course, there was no breathing apparatus. Reports from the period suggest divers would typically spend up to a minute under water. To aid the dive, the diver would have cotton wool put in his ears and a sponge bound over his mouth.

To reach the sea bed, divers would hold a weight – such as a heavy stone, and when fully descended they would scrape the oysters off the oyster bed with a sharp knife, putting as many as possible into bags fastened round their waists.

When the diver was finished, a ‘puller’ would haul the diver up on a rope. The diver would tug on the rope to show he was ready to come back up. The Irish News noted that ‘As soon as a diver comes up after the first dive of the season his nose bleeds, but if this does not happen it is taken as a bad sign and he will not dive again.’

The article goes on to state that ‘the divers in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. were mostly Arabs, who could stay under water much longer than the Hindu divers of Ceylon.’

‘Jazwa’, Nakhuda and ‘Tajir’ [Tajaa]

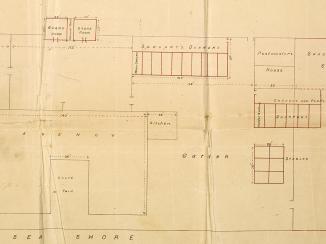

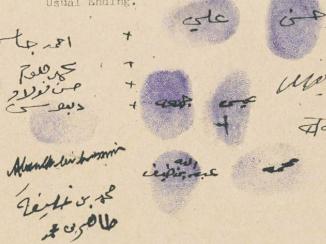

Because of the manual nature of the labour, many different roles were integral to the trade, and they were organised hierarchically.

The British noted the transliterated names of the roles they observed: divers were generally known as ‘jazwa’ and were ranked by the number of shares in the profit they received. A ‘kais’ was a diver who received three shares, while a ‘seib’ was a puller who received two shares in the profits of the catch.

The nakhuda was the boat captain, who received one fifth of the total profits after deducting expenses, while the ‘tajir’ was the land captain, who financed the sea nakhuda. The ‘jeudi’ was the agent or ‘wakil’ of the nakhuda, who received the share of three divers. The ‘tabakh’ was the cook, usually a boy, paid by the divers.

An ‘azal’ was a diver who went out in the boat of a nakhuda but dived independently, keeping his own catch, paying the nakhuda one fifth of his profits, and paying his own keep.

Diving Systems

There were various diving systems in operation, all of which were bound up with the means of financing the operation, and had differing implications for the financial security of the individuals involved.

In one of them, called ‘amil’, the tajir financed the nakhuda without charging him any interest. In return, the tajir had the option of buying all the pearls in the catch.

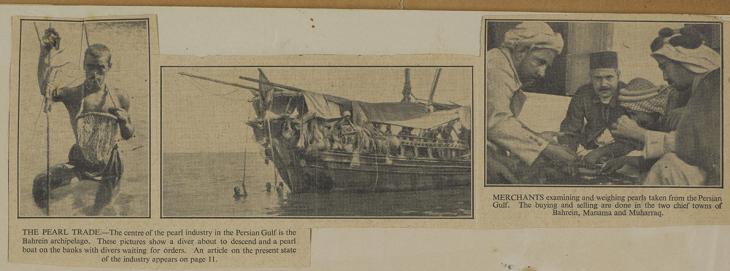

A note in the file describes how the shells were opened in the evening under the strict supervision of the nakhuda. They were then sold (either on land or on the ‘tawasha’ boats upon the arrival of buyers at the pearl banks) to the best advantage of the crew. Two thirds of the crew had to be present as witnesses to the sale, according to one of the diving rules. However, the note goes on to state that there was little doubt that in many cases some of the pearls were kept back and sold ‘independently’ by the nakhuda.

Another system was called ‘azal’, under which three or four men hired or owned a boat independently. This system required capital, but left ‘the least opportunity for cheating’.

Profit or Loss

The value of a pearl depended on its size, shape, colour and freedom from defects. However, the merchants could not tell either the quality or quantity of those in the oysters they bought – so sometimes they lost out on the deal, and at other times they made a fortune.

Some nakhudas took on too much risk and went bankrupt. Their cases were heard in a special diving court. However, it is evident that the majority of divers were permanently in debt to their nakhudas. Clearly the risks – financial and physical – to those involved in pearl diving were high, but so too were the potential profits.