Overview

Lord Curzon, before becoming Viceroy of India (1899-1905) and Foreign Secretary (1919-1924), wrote that ‘If the correspondence [regarding railway construction in Persia (Iran)] that has passed from the various legations in Teheran [sic] to the great capitals of Europe, and more especially to St. Petersburg and London, were collected, it would provide a bonfire that would blaze for a week’ (IOR/L/PS/20/C43/1, p. 614). Much the same can be said of railways beyond Persia. Curzon himself, as a committed imperialist, was keenly interested and involved in the development of railways across Central Asia, Anatolia Peninsula that forms most of modern-day Turkey. , and the Arabian Peninsula, due to the strategic and military functions they could perform.

Railways constituted a technological innovation that transformed commonly held ideas and experiences of space and time, reconfigured national and global economies, and rewrote the military strategy handbook. They therefore inevitably became central to the language of diplomacy and international relations. For a hundred years, between the mid-nineteenth century and the end of the Second World War, railways in Asia were an obsession of the imperial powers. Thankfully, Curzon’s imaginary bonfire was never lit, and much of the correspondence regarding Britain’s involvement in these railway projects has survived as part of the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records.

Pawns of Persia

Starting with the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway in 1891, railways became chess pieces in the strategic rivalry between Russia and Britain, which was already playing out in Persia at the time. The idea that Russia might be capable of transporting an army so close to Britain’s possessions in India altered the way the latter thought about the defence of its empire. Naval superiority had previously been the greatest defence for a region that could only be reached overland from Europe with great difficulty. However, with the improvement in communications and transport that railways provided, Britain now perceived a much greater threat materialising just beyond India’s land borders.

The two powers had vied for dominance in Persia throughout much of the nineteenth century, during the so-called ‘Great Game’. As well as providing a rapid means of military mobilisation, rail lines were believed to be an effective means of exerting political influence, and both Russia and Britain sought to extend theirs in such a way. Even after the signing of the Anglo-Russian Convention in 1907, which went some way toward delineating the boundaries of influence in Persia, relations and conflicts of interest between the two empires were often articulated through negotiations over railways. Of concern for both parties was how to outflank Germany’s growing presence in the region, and the latter’s planned rail link from Baghdad to the shores of the Gulf.

The Baghdad Railway

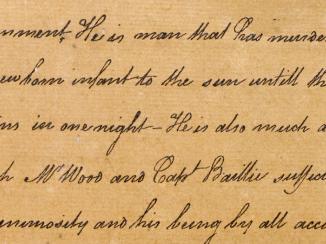

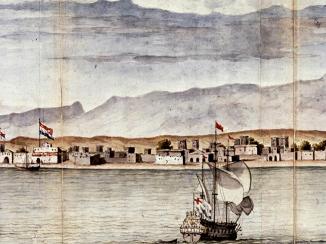

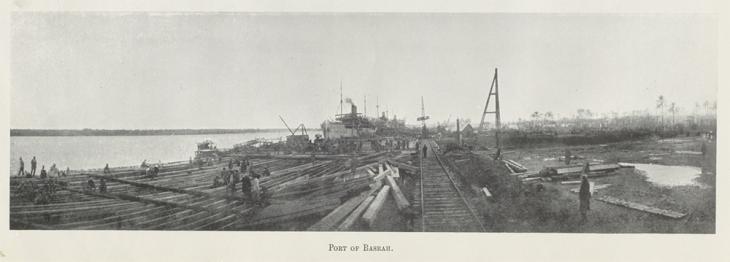

In 1903, Germany began working on an extension of the railway from Konya to Baghdad, and ultimately onward to Basra and the Gulf. Both the German and Ottoman powers sought British assistance, but opinion in Britain was divided over whether to support such an extension. Some thought that German penetration of Mesopotamia [modern Iraq] would come at the cost of British influence there. An additional issue was that Germany might obtain access to suspected oil fields in the region. Most worrying to British officials, though, was the potential compromise of their privileged position in the Gulf, and the consequent threat posed to India. However, such progress in global communications was considered inevitable, and many thought it vital that Britain play a leading part in the process.

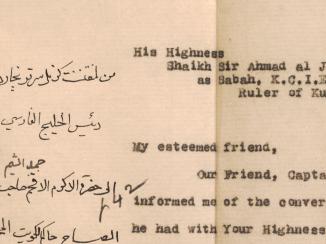

As a result, official British policy switched back and forth several times. Britain’s initial belief that its consent was essential for the project to get off the ground was proven very wrong, and during the first decade of construction a great deal of discussion took place between the governments and interested venture capitalists of Britain, Germany, Ottoman Turkey, France, and Russia. The concerns over loss of influence led directly to Britain’s attempts to control any extension of the line to the shores of the Gulf, and to negotiations with Ottoman authorities over the status of Kuwait, resulting in the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913.

Trans-Arabian Railway

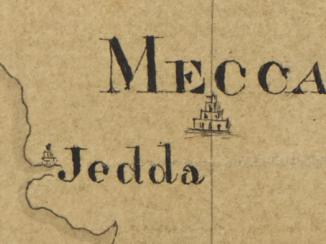

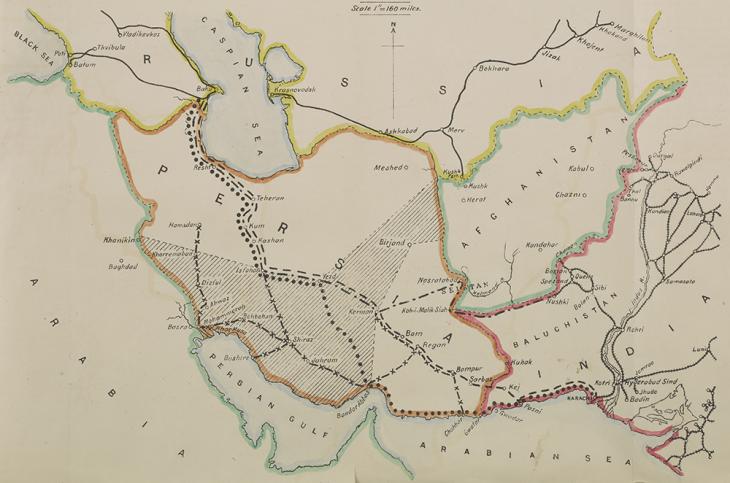

An overland route to India, controlled by Britain, had long been a dream of British imperialists. From the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, where the Royal Navy provided security, through parts of Arabia and Persia dominated by Britain, to the frontiers of the Indian Empire at either Quetta or Karachi, the route was expected to bring economic, political, and strategic benefits. The eastern part of this vision related to the rivalry with Russia, as well as Britain’s efforts to dominate Persia; the western part was tied up with Britain’s ability to control parts of Arabia and the Gulf.

As far back as the 1850s, Britain had sought permission from Ottoman authorities for a railway along the Euphrates valley that would link the Mediterranean to the Gulf. In addition to their strategic concerns, British officials saw the region as ripe for development, with great potential for economic returns. With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire following the First World War, and the carving up of the Middle East by Britain and France to suit their own needs, the proposed trajectory of the route shifted further south to remain in zones of British control, terminating in Haifa rather than Alexandretta.

No longer of any real commercial value, a rail line through the desert from Baghdad was now considered necessary instead to protect a planned pipeline for extracting oil from Mesopotamia, and to support a new air route from England to India. But the line never materialised. Britain conducted surveys in the 1920s and the pipeline was built, but enthusiasm for a railway faded. Just as technological developments triggered the rise of the railway, the invention of the internal combustion engine brought about its decline. Cheaper, faster, and more agile, air travel and the motor car became the focus of an ailing empire struggling to project the power it once did.

Railways were transformative in many ways and on many levels. They help us to think about the relationship between technology and power. The many files within the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records devoted to the subject reveal the impact they had on empire-building, and on relations between the great powers of the time. Railway construction across the British Empire and beyond was tied to questions of material extraction, infrastructures of violence, imperial strategy, capital investment, indentured labour, and political, commercial, and social penetration. Some of the answers to such questions may be found in the records that were held at the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. and are now digitised on the Qatar Digital Library.