Overview

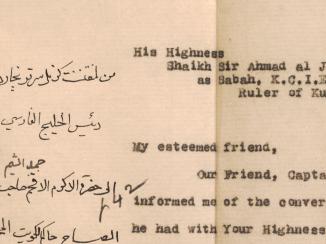

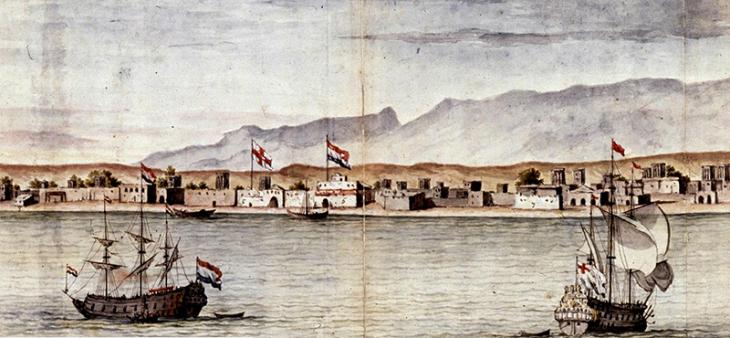

In the summer of 1767, just four years after the establishment of the East India Company’s (EIC) Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. at Bushire, William Bowyear, the Resident, wrote to Bombay despairing of ‘a total stagnation of all business’.

Karim Khan Zand, the ruler of Persia, had closed the roads that led to Bushire from the Zagros Mountains to the northeast in an attempt to force the sheikhs of the port to submit to his rule. Many merchants had left town, preferring to return to Shiraz where business still thrived. The English were left feeling stranded.

The Exit Strategy

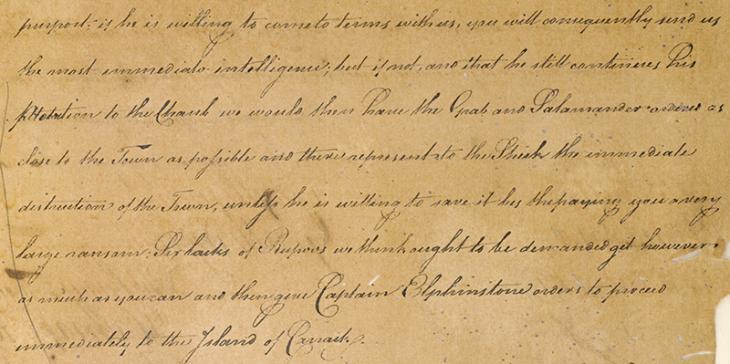

Outraged by the Khan’s actions and concerned for the health of the Company’s profits, Henry Moore, the Agent at Basra and Bowyear’s superior, wrote to the Resident outlining a plan to withdraw from Bushire. Terms that would safeguard the EIC’s trade and privileges in the region were put to the Khan in Shiraz.

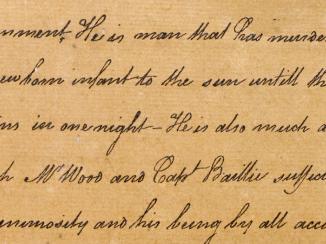

If they were not accepted, Moore wrote, Bowyear’s orders were to abandon the town and make immediately for the island of Kharg, home to the increasingly powerful but dangerously unpredictable Arab sheikh, Mir Muhanna, one of Karim Khan’s most troublesome enemies.

A Persian Gulf Dynamic

Switches of allegiance and location such as this were not rare occurrences in the Gulf throughout this period, particularly amongst groups of merchants. The Dutch left Bandar Abbas for Kharg in the 1750s due to instability; Arab merchants joined the English in migrating to Kuwait during Karim Khan’s siege of Basra in 1775; pearl traders were lured to Zubarah 18th-century town located 105 km from Doha. by low taxes in the same decade; and merchants and brokers from the Indian subcontinent came and went wherever money could be made.

This fluidity of merchant groups – moving to where taxes were low and stability was high – had been a dynamic of Gulf history and the wider Indian Ocean basin for many centuries. It was especially characteristic of the turbulent period during which the Bushire records began. The EIC was just one group among many within a flexible commercial class that sought profit where it could most easily be found.

A Template for Multinational Corporations

This remained the case up until the British, whose grip on India was tightening, began to impose themselves on the Gulf region through their naval strength from the 1820s onwards. This brought some stability to the region and shored up those rulers who happened to be in power at the time.

This points to one of imperialism’s most enduring legacies. Military and moral support for companies such as the EIC gave rise to a global form of capitalism that now transcends the power of nation states. It can be seen in today’s multinational corporations – groups that exhibit a similar mobility to those trading in the Gulf two hundred years ago – and in the international wars that involve them.

Certainly, without military backing, the EIC would not have become as powerful as it did. But it was through a combination of increased military involvement and its mobile response to trading climates that made the EIC more powerful than those other contending traders in the Gulf, particularly Bushire.

Trade, Wherever Possible

Despite the stagnation of trade, there was no withdrawal from Bushire in 1767. It was discussed again a year later, with the situation becoming ever more volatile and the English fearful of attack from several directions.

Finally, in early 1769, the EIC left Bushire, though they returned in April 1775 after coming to terms with Karim Khan, who had settled his differences with the Bushire sheikhs.

The correspondence throughout these decades provides us with a commentary on the highs and lows, the tos and fros of the EIC, just one group among many trying to make a living, through trade, wherever it could be found along the coast of the Gulf.