Overview

The name Mīr Muhannā (d. 1769) is much celebrated in Iran today as a heroic underdog who stood up to imperialism and won. He defeated the Dutch, embarrassed the English and refused to pander to the will of Iran’s rulers of the time. He even has his own computer game.

In his day, he was a major source of concern for all those who traded along the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. and his exploits were an early factor, beyond purely commercial concerns, that led the East India Company to first become entangled in the politics of the region. The early correspondence of Britain’s Bushire residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. provides a fascinating insight into these events.

Rise to Prominence

Mīr Muhannā first attracted attention due to the ruthless means by which he came to power. Unimpressed with the solicitous approach to the demanding Dutch East India Company his father adopted while governing Bandar Rig, Mīr Muhannā murdered him and burned his mother alive.

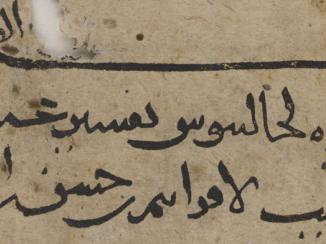

The violence resumed months later when, in a bid to take complete control of the town, he killed his brother and fifteen other relatives. Reports at the time claim he ‘threw his sisters into the Sea & cut off 65 of his relations in one night’ and, horrifically, ‘exposed his wife and new born infant to the sun untill they Expired’. Whether this is wholly accurate or not, it fed a reputation for brutality and the fear the Mir had managed to instill in his enemies.

![Extract of a letter from William Bowyear, East India Company Resident at Bushire, and his assistant, James Morley, to Henry Moore, East India Company Agent at Bussora [Basra], dated 13 July 1767. IOR/R/15/1/1, ff. 125r](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_r_15_1_1_0288_cropped.jpg?itok=dnrt333G)

With a fleet and followers, Mīr Muhannā took to the Gulf seas and the hinterland of Bandar Rig and for many years was an unwelcome challenge to the authority of Karim Khan Zand, ruler of Iran (1750–79), and the commercial ambitions of the European powers.

The Europeans Outsmarted

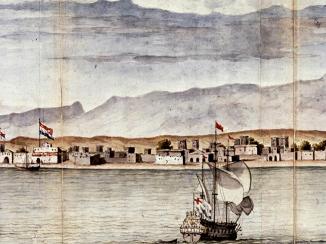

In 1765, English ponderousness allowed him to escape a Persian force at Bandar Rig and withdraw forty kilometres off the coast to Corgo, Kharg’s smaller neighbouring island. From there he fought off a belated English attack. This gave him the confidence to take Kharg from the Dutch, something he achieved with astonishing ease. He lured them out of their fortress on the pretence of negotiation and then simply took it from them.

The Mir showed his cunning again a few years later when, in May 1768, with grants of trading privileges from Karim Khan at stake, the English made a second attempt against the island.

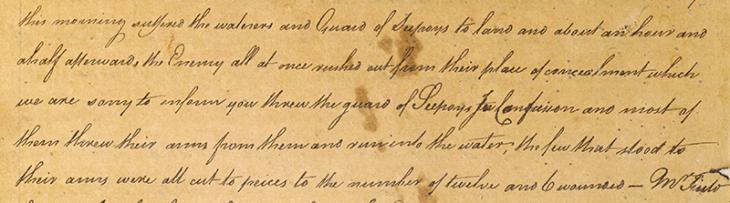

In times of war, English ships would carry units of infantry, often made up of soldiers from India known as ‘sepoys’. Such a ship, having initially failed in a first assault against Kharg, was cruising off the island for some days and required watering. A freshwater well on Corgo served the purpose, and, after scouting the island the day before, a small unit of infantry rowed ashore to fetch water from it, unaware that Mīr Muhannā’s men had transferred to the island overnight and ‘hid themselves in trenches in the sand’.

Once the Indian troops were far enough from the safety of the shore, the Arabs burst from their cover and attacked the sepoys Term used in English to refer to an Indian infantryman. Carries some derogatory connotations as sometimes used as a means of othering and emphasising race, colour, origins, or rank. , some of whom ‘threw their arms from them and run into the water’, while the rest ‘were all cut to pieces’. The English returned to Bushire, tail between legs.

On the Company’s Doorstep

On the mainland, too, the Mir proved troublesome, as illustrated by an incident in October 1764. With the majority of Sheikh Sa’dun of Bushire’s men engaged at sea against his fleet, Mīr Muhannā took the opportunity to send a few of his men into the country around Bushire.

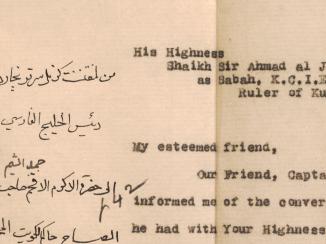

They plundered adjacent villages and, in a show of bravado, ‘have several times come Pretty near the Town’. They even stole a mule and an ass belonging to the Company, much to the chagrin of Benjamin Jervis, the Resident at the time, who described them as ‘a miserable sett of cowardly Banditti’. Worse still, they cut off the ears of the waterman who was leading the animals.

![Extract from a letter from Benjamin Jervis, East India Company Resident at Bushere [Bushire], to Peter Elwin Wrench, East India Company Agent at Bussorah [Basra], dated 10 October 1764. IOR/R/15/1/1, f. 63v](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_r_15_1_1_0139_cropped.jpg?itok=W3kbCk_z)

Eventual Downfall

The political wrangling about how to deal with the threat of Mīr Muhannā continued throughout most of the 1760s between Karim Khan and the English in Basra, Bushire and Bombay. It was partially as a result of the Mir that the earliest diplomatic missions were sent to Shiraz by the English in 1767–68, and this process of further political involvement with the Persians was never fully reversed.

In the end it was Mīr Muhannā’s own people who finally brought this story to an end. Having had enough of the severity of his rule, they seized his fortress on Kharg and chased him from the island. He found his way to Basra where he was captured by the Turks and eventually executed on 24 March 1769.

Nonetheless, he remains a strong presence in the early correspondence of the East India Company, his remarkable career, spanning many years, reflected in its pages. In his native Iran, too, his memory and legacy live on.