Overview

Plans and Preparations

Until the completion of the Suez Canal in 1868, the only feasible way to travel between Europe and East and Southeast Asia was a lengthy sea journey around the Cape of Good Hope (such as those recorded in the IOR/L/MAR series). These journeys were not only long and laborious, but also fraught with danger. Trade and communications between the United Kingdom and her colonies and trading posts in Asia and the Pacific relied on a process that was highly vulnerable to adverse weather conditions and, during times of war, hostilities from other naval powers.

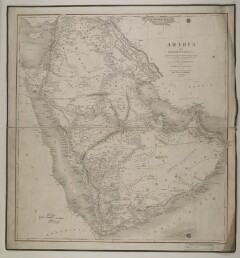

The Euphrates Expedition of 1835-36 aimed to explore the possibility of establishing a permanent steam-boat service on the Euphrates River as part of an overland route linking the Gulf to the Mediterranean, and therefore bypassing the Cape route entirely. In July 1834, the UK Parliament’s Select Committee on Steam Navigation to India reported that, unlike the route via the Red Sea to Suez, which could be restricted by monsoon winds in the Indian Ocean, steam navigation ‘would be practicable between Bombay and Bussora [Basra] during every month in the year’ (IOR/L/MAR/C/573, f. 75v). It consequently recommended a grant of £20,000 towards determining the navigability of the Euphrates during the winter months.

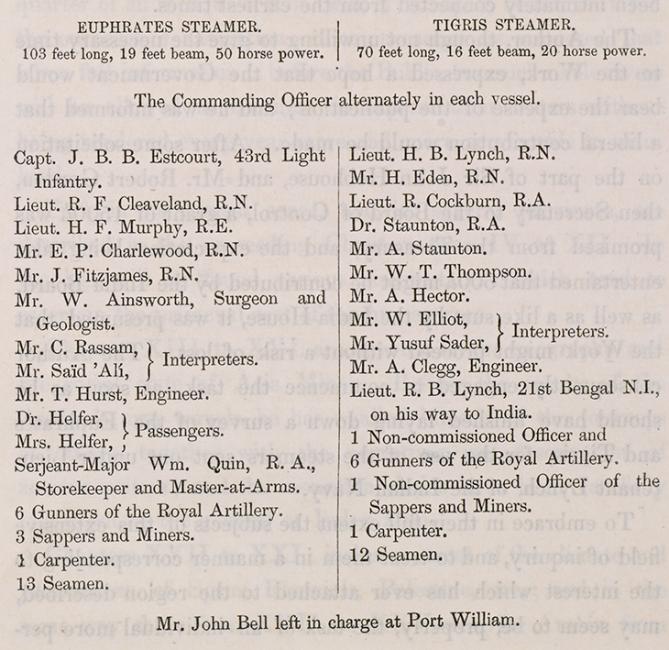

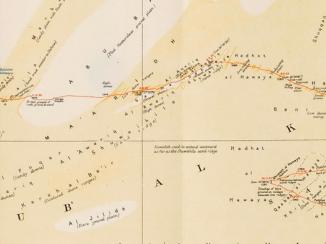

Parliament approved the grant in early August, and preparations for the expedition quickly got under way. Command was given to Captain Francis Rawdon Chesney, whose 1830 survey of the Isthmus of Suez and 1831 survey of the Euphrates had been among the evidence considered by the Select Committee. The two iron steam vessels the expedition would use, named Tigris and Euphrates in honour of the rivers they would be traversing, were to be transported in pieces and assembled when needed. Those pieces, and the expedition’s crew, departed from Liverpool aboard the George Canning on 31 January 1835. They arrived at Sowedich [Samandağ, modern-day Turkey] in April and then travelled overland to Bir [Birecik, Turkey] on the banks of the Euphrates, where the steamers were assembled and the survey commenced.

Oversight and Obstructions

Responsibility for the expedition initially lay with the India Board, the branch of the British Government that oversaw the East India Company. However, Chesney was under orders to answer directly to the Company-run Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. upon the expedition’s arrival at Basra. To facilitate this handover of responsibility, the India Board wrote to the Company in February 1835, suggesting they purchase the two vessels from the British Government. Not only did the Company decline this suggestion, but ‘nor [did] they wish to engage in any way in the Expedition’ which had been planned ‘without [their] participation or concurrence’ (IOR/L/MAR/C/573, f. 29r). By May, the Company had been persuaded of the potential advantages to India of a regular service on the Euphrates and had agreed to advance up to £5,000 to the expedition. Nevertheless, they remained reluctant partners, making it clear that this was a one-off payment in exchange for taking possession of the vessels after the end of the expedition, and cautioning that the eventual expense of establishing the route might ‘be far in excess of any advantage that could arise from it’ (IOR/L/MAR/C/573, f. 52v).

The entirety of both the Euphrates and the Tigris lay within the territory of the Ottoman Empire, whose cooperation with the project was therefore essential. In November 1834, Foreign Secretary the Duke of Wellington wrote that the expedition ‘is undertaken with the permission of a friendly power, without whose countenance and cooperation, success cannot reasonably be expected’ (IOR/L/MAR/C/573, f. 87v). The Ottoman Government may have granted that permission, but in reality many of the regional governors answered to Muhammad ‘Ali, the semi-autonomous Governor of Egypt. At various stages, the expedition was denied vital passage or supplies until an Ottoman official had applied directly to ‘Ali for permission. British officials at the time suspected this to be intentional obstructionism from ‘Ali with possible Russian influence. An unsigned memorandum of 13 January 1836 theorised that Russia might view the Euphrates, the source of which lay close to their territory in Armenia, as a potential route to challenge British power in the Gulf. It further suggested that a British presence on the river would remove this option. Whether or not this was true, the expedition suffered serious delays.

Tragedy and Termination

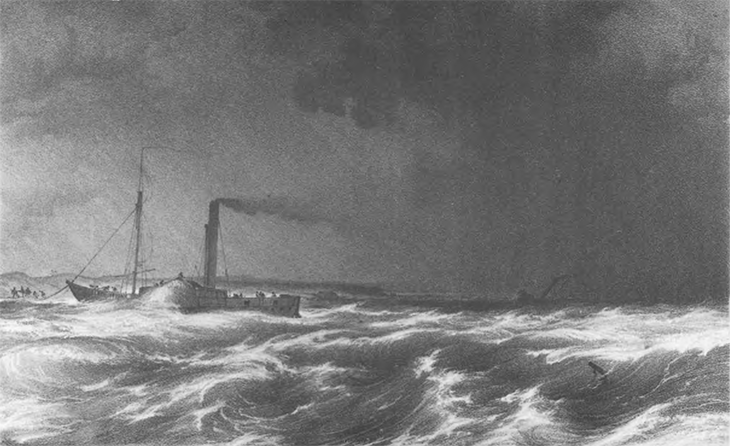

On 21 May 1836, the expedition suffered a tragedy far beyond delays or frustrations. The steamers had departed from Mauson [Al-Muhasan, Syria] when they were caught in a storm that, in the words of one of the officers, ‘came hurling on towards us with the most fearful rapidity’ (IOR/L/MAR/C/574, f. 183v). The crew of the Euphrates were able to secure her to the bank, but the Tigris was blown back into the centre of the river and sank within minutes. Around half the crew, including Chesney, managed to clamber ashore, but twenty men drowned.

By June the expedition had completed its survey of the Euphrates, and the remainder of the year was spent on exploratory surveys of the Tigris and the Karun. The following year, The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society published an account of the expedition written by Chesney and his colleague William Ainsworth. In its introduction, The Journal proclaimed the expedition a success, stating that ‘everything which could reasonably have been looked for, has been accomplished’ (p. 411). Meanwhile, Britain’s Resident in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. wrote that the establishment of a permanent steam service on the Euphrates was ‘worthy of the deepest consideration’ (IOR/L/MAR/C/574, f. 342v). He also suggested ways in which it could strengthen the British position in the Gulf, not only by increasing the speed and efficiency of communications, but also by expanding Britain’s naval presence, which could assist in the suppression of so-called “piracy”. Further explorations were carried out in the 1840s, but in 1854 preparations began for the building of the Suez Canal and an official overland route between the Mediterranean and the Gulf never became a reality.