Overview

What are the IOR/L/MAR files?

On East India Company (EIC) voyages, it was regular practice for the commander and other principal officers of a ship to keep a detailed account of the voyage in a journal or log-book. Journals for voyages that visited ports in the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula on the Qatar Digital Library (QDL) are part of the collection of ships’ journals, logs, and related records which form the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records series IOR/L/MAR/A (1605-1705) and IOR/L/MAR/B (1702-1856). The IOR/L/MAR/A files also include ships’ ledger books, containing financial records of crew members as well as crew lists.

![Crew list in the ledger of the Montagu for its voyage to Surrat [Surat] in 1699-1702. IOR/L/MAR/A/CXXV, f. 10v](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_l_mar_a_cxxv_0025.jpg?itok=hiXBq1NT)

The surviving records of the EIC and (after 1858) the India Office’s management of its marine affairs constitute the IOR/L/MAR/C series of Marine Miscellaneous Records. Files from this series which relate to the Gulf and the Arabian Peninsula are also available on the QDL.

What is the historical context of the records?

The EIC’s charter of incorporation, dated 31 December 1600, provided the Company with a monopoly of all English (and later British) trade east of the Cape of Good Hope. Dutch voyages to Southeast Asia in the late sixteenth century had encouraged expectations among English merchants of high profits to be made from the spice trade, and led to concern regarding possible Dutch dominance over eastern trade. Thus, on 13 February 1601 the English East India Company’s first fleet of four ships set sail for the pepper-producing islands of Java and Sumatra.

Between 1601 and 1614, eleven more Company fleets were sent to Asia. Each of them operated as a ‘separate stock voyage’, meaning that they were financed separately, kept their own accounts, and paid their own dividends. Then in 1614 the separate voyages were replaced by a single joint stock, which provided continuous financing for annual commercial voyages to Asia.

Initially the Company either bought or built its own ships. However, after the closure of the Company’s dockyard in 1652, hiring ships from private owners became the general practice. While the ship owners were responsible for providing the crew, the officers were appointed by the Company, which also tightly controlled the pay for all ranks of crew, private trade by crew members, and charges for passengers.

The first twelve voyages all had Indonesia as their primary destination, and the first English ‘factory’ or trading post in Asia was established at Bantam [Banten] on Java. However, England’s main export of woollen cloth proved unpopular in Southeast Asia, as it was particularly unsuitable for the tropical climate. Indian cottons, on the other hand, were discovered to be in high demand.

The Indian subcontinent comprised several distinct trading areas, which were each commercially linked to a number of trading regions across Asia. Gujarati ships, for example, had long been exporting cotton to Java and Sumatra in return for pepper and spices, as well as trading with ports in the Red Sea and the Gulf.

The ships of the Third Voyage were instructed to sail to Bantam via the Arabian Sea and Surat in order to capitalise on these existing commercial networks, to discover potential markets for English woollens, and to explore new possibilities for trade. It was in Surat, the principal port of the Timurid or Mughal Empire (1526-1857), that the Company established one of its main ‘factories’ in India.

In addition to Bantam and Surat, other destinations included Safavid Persia [Iran], where raw silk was obtained, and Mocha, where coffee could be purchased. By the 1660s, coffee had become the staple export of the Red Sea ports.

Other ports of call in the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula included Jeddah, Aden, Socotra, Masirah, Muscat, Basra, Bushehr, Qishm, Bandar Abbas, and Jask.

Additional destinations included Madras [Chennai], Bombay [Mumbai], Calcutta [Kolkata], Calicut [Kozhikode], Borneo, and Japan. The voyages also encompassed other locations in Asia, Africa, South America, and the Caribbean.

By the early 1800s, 40-50 ships were usually sailing on EIC voyages each year. The renewal of the Company’s charter in 1813, however, limited its monopoly to trade with China, and its remaining monopolies were abolished under the Charter Act of 1833, when it ceased to exist as a commercial organisation.

What are the contents of the IOR/L/MAR files?

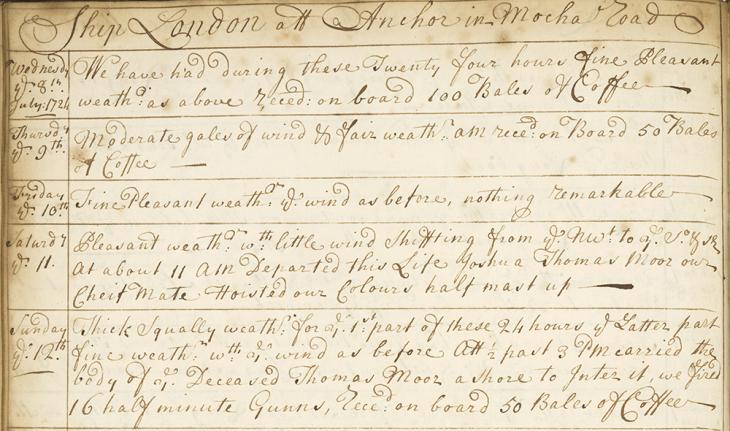

The daily entries in the ships’ journals mostly record the arrival and departure of ships from various ports of call, wind and other weather conditions, activities of crew members, encounters with other ships, disease and deaths among the crew, punishments inflicted on crew members for various offences, and occasional sightings of birds, fish, and other marine animals.

![Entries for 20-21 March 1784 in the journal of the Europa, when it was sailing from Muscat towards Bussora [Basra]. IOR/L/MAR/B/425E, f. 113r](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/ior_l_mar_b_425e_0231_0.jpg?itok=9AsmU6hj)

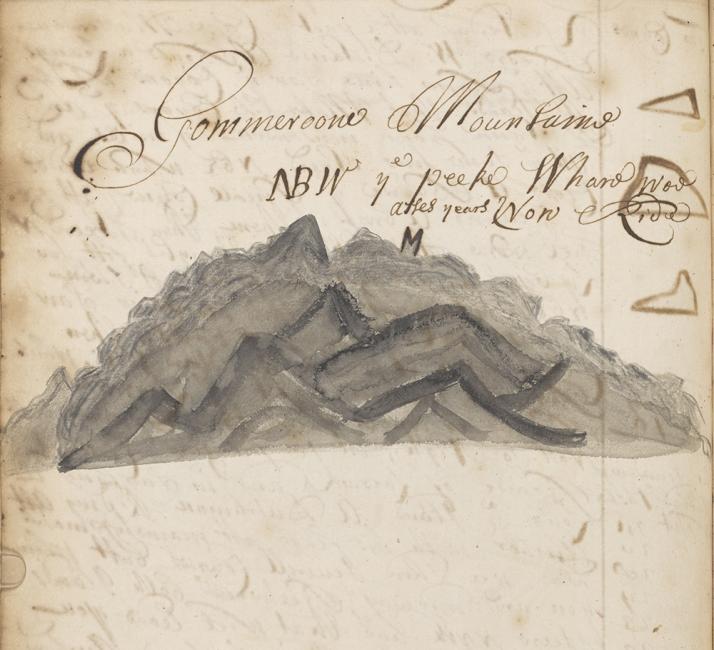

When the ships were in port, the entries also record goods and provisions being loaded onto the ships, and goods and chests of treasure being unloaded and taken ashore for trading purposes. Entries when the ships were at sea additionally record navigational information, including measurements of latitude, longitude, variation, and the courses of the ships, as well as sightings and bearings of land. Sketches, mostly of coastlines, are also occasionally found in the journals.

Between the 1620s and the late eighteenth century, the EIC purchased and transported thousands of enslaved people from Africa (especially Madagascar and Eastern Africa), India, and Southeast Asia, for use as slave labour at its various establishments including, in particular, the EIC factory An East India Company trading post. at Bencoolen [Bengkulu] on Sumatra. At least three of the ships’ journals on the QDL include brief references to the acquisition of enslaved people (IOR/L/MAR/A/XLVII, f. 29r and IOR/L/MAR/A/XLIX, f. 29v, entries for 23 July 1628) and the deaths of enslaved people on board ship (IOR/L/MAR/A/CIII, entries including 3 September and 13 September 1698).

In addition to the IOR/L/MAR/A ledger books and crew lists, the IOR/L/MAR/B journals sometimes include lists of crew members, passengers, Company soldiers, and local Indian and Arab sailors (or ‘lascars’) employed in various capacities, who were transported on EIC voyages.

Several files from the IOR/L/MAR/C series of Marine Miscellaneous Records are also available on the QDL, including: correspondence relating to the Euphrates expedition of 1835-36 (IOR/L/MAR/C/573 and 574); journals and other records of journeys in the Gulf, the Red Sea, the Arabian Peninsula, and India (IOR/L/MAR/C/570 and 587); various papers concerning the trade of the Red Sea and the Gulf dated 1773-1813 (IOR/L/MAR/C/891); and a survey of the East Coast of Africa in 1810-11 (IOR/L/MAR/C/586).

What is the significance of the records?

The EIC preserved the ships’ journals as evidence of its fulfilment of the terms of its charter. They were also available for any of the Company’s commanders for consultation. Moreover, successive hydrographers used the often detailed observations and navigational information in the journals to improve the Company’s marine charts.

The IOR/L/MAR files constitute an extraordinarily rich and valuable set of primary sources for numerous areas of research, including: the history of global trade networks; encounters between British merchants and crews and diverse peoples in different parts of Asia, Africa, and elsewhere; rivalry between European powers and the origins of British imperialism in Asia; long-distance marine navigation; the experience of everyday life on board ship and during lengthy voyages; and historic weather patterns over more than two centuries.