Overview

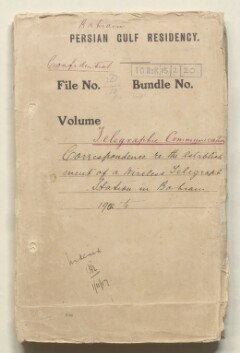

Before 1916 wireless telegraphy did not exist in Bahrain. Anyone wishing to communicate telegraphically had to send messages to Bushire by the fortnightly mail steamer. The email of its day, wireless telegraphy, once it came to the islands, helped revolutionise communications and played a vital role in helping to modernise Bahrain.

Wireless telegraphy is a communications method for sending messages in Morse code without connecting wires. The written messages that result are known as telegrams. Later superseded by radio as a means of transmitting voice messages, it long continued as a medium for business and official communications.

Commerce and Trade: The Telegraph as an ‘Inestimable Boon’

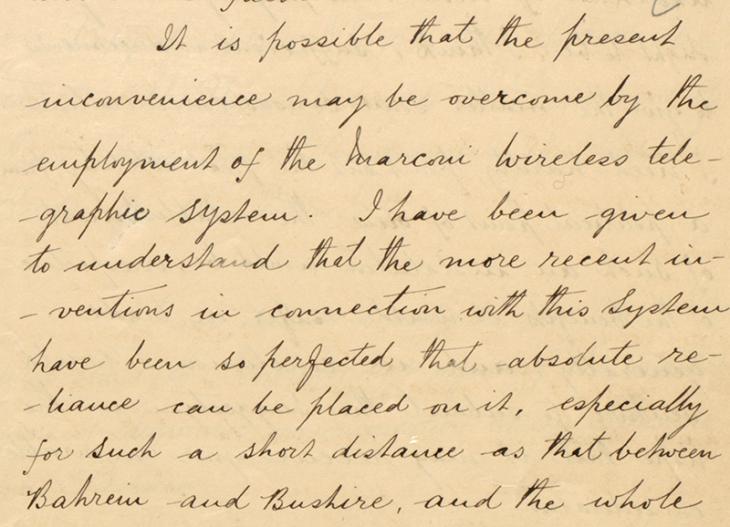

In view of Britain’s position as the dominant colonial power in the Gulf at this period, it is no surprise that the British administration in Bahrain was instrumental in bringing the technology to the island. A letter from the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain to the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in Bushire in 1902 set out the advantages. But the letter shows that the initiative actually came from British Indian traders in Bahrain, who had made repeated representations to the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. to establish better communications with India so that Bahrain could have the same facilities enjoyed by other places in the Gulf ‘of less commercial importance’.

Speed of communication was vital in particular to the pearl trade, which by its speculative nature needed to be able to increase or withdraw orders quickly. Nothing came of the proposal and the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. twice had to renew his demands, in 1907 and 1913, forecasting that wireless communication would be an ‘inestimable boon to the merchants and traders of the Islands’.

He drew attention to the advantages to be gained by the British, both from being seen to be taking a closer interest in improving conditions in Bahrain and by facilitating better communications with Royal Navy ships in the Gulf. By 1914, the Government of India had given permission and work was under way.

Stone from ‘Old Phoenician Tombs’

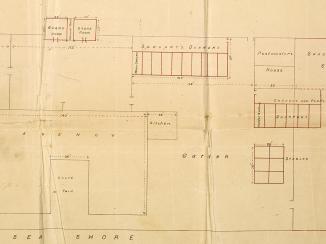

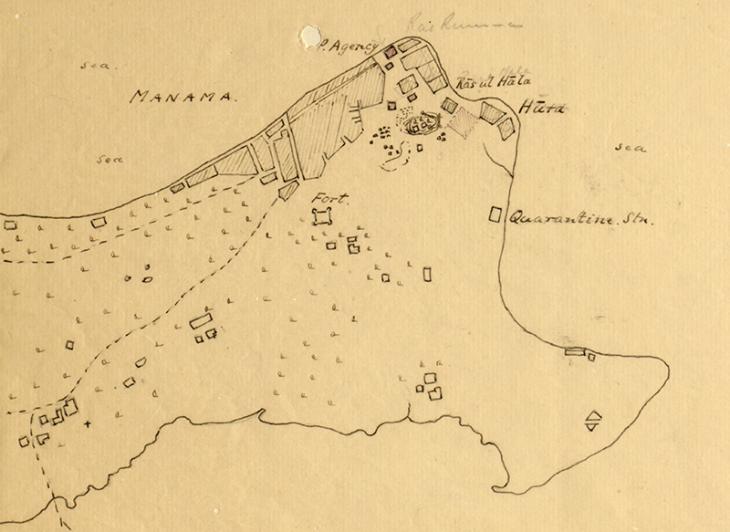

Less than a mile from the Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. and the town of Manama, a site 700 feet long and 500 feet in breadth was selected. The land was presented as a gift by Sheikh ‘Īsá bin ‘Alī Āl Khalīfah of Bahrain.

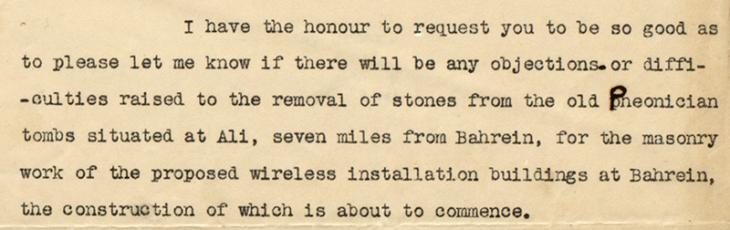

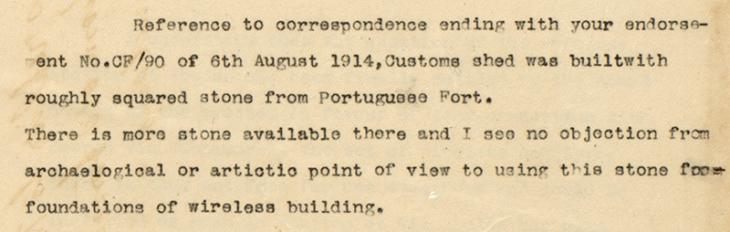

Obtaining stone for the construction of the building proved difficult. One suggestion was that stone should be removed from ‘old Phoenician tombs’ at A’ali (a site in northern Bahrain, famous for its burial mounds), as the stone obtainable from the tombs was much superior to the kind generally used in Bahrain for building purposes. Actually, those tombs belonged to the indigenous Dilmun civilisation, which had flourished in ancient times in Bahrain and other parts of the Gulf. Fortunately, that proposal was turned down, but permission was given to use roughly squared stone for the foundations of the wireless building from the Portuguese Fort – today the Qal’at al-Bahrain, a UNESCO world heritage site A place that is listed by the UNESCO as of special cultural or physical significance. .

Stray Bullets

In 1915, when the wireless station was almost complete, a problem arose. The supervisor at the site complained that someone had been firing bullets in the area, some of which had passed through the compound. He feared that further damage might be caused if an adequate number of ‘naturs’, or watchmen, was not provided. It is not apparent from the papers who was actually doing the firing or why, but it is clear that the British and Bahrain authorities were concerned about potential damage to the building and equipment at the site.

In response, the Sheikh of Bahrain gave orders for watchmen to be taken on and warned people in the area not to enter the building or cause any damage. However, security continued to be a problem until 1916. Eventually it was proposed that the station should be enclosed within a barbed wire fence.

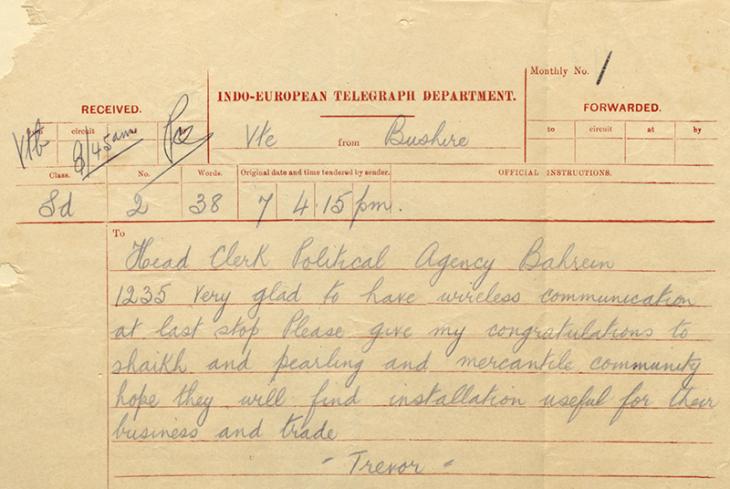

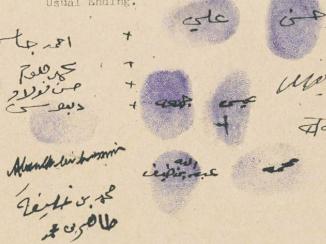

‘Heartfelt Thanks’ for the Telegraph

Despite these problems, the new wireless station opened in March 1916. Letters of congratulation were received at the Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. from many people in Bahrain, including Sheikh Isa. Appropriately, in view of the pressure exerted in 1902 by the British Indian traders, the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. chose to send a telegram from Bushire congratulating the pearling and mercantile community on the advent of wireless communication, which he hoped they would find ‘useful for their business and trade’.

In reply, the merchants expressed their ‘heartfelt thanks’ and hopes that they would ‘soon have the pleasure of making use of the installation’. The continuing importance of the pearling trade to the Bahrain economy in the 1920s demonstrates the undoubted uses to which the new technology was put.