Overview

The Mamlūk sultans of late-medieval Egypt and Syria, like other rulers throughout history, sought reliable means for interpreting the world around them and for predicting future events. Many manuscripts copied within the Cairo Sultanate survive and a number of them address various methods of interpreting the present or foretelling the future. Produced for politically high-ranking patrons, some of these manuscripts allow us to read over the shoulders of Mamlūk sultans and amīrs (military commanders) and show us the place of prognostication in Mamlūk politics.

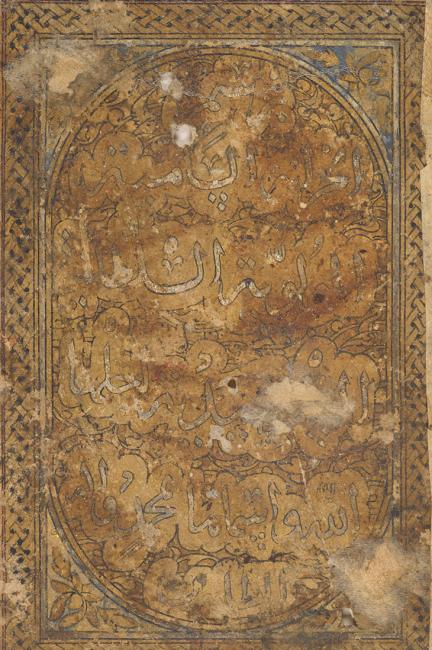

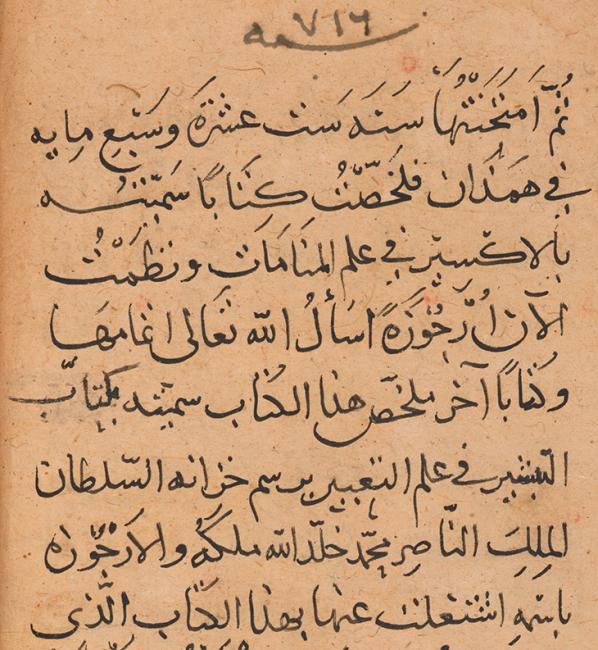

Dreams and Dedications: The Book of the Full Moon

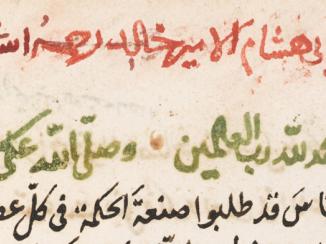

One such manuscript is Or 7733, a manual of dream interpretation called the Book of the Full Moon on the Science of Dream Interpretation (Kitāb al-Badr al-munīr fī ʿilm al-taʿbīr), written by Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAlī ibn ʿUmar ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī al-Baṣrī al-Maṣrī, known as Ibn Jaydān. The manuscript is a holograph (i.e. it was copied by the author himself), completed on Wednesday 2 Rabīʿ II 727 AH/25 February 1327 CE for the sultan’s treasury. Ibn Jaydān explains in the preface that he composed the manual for the Mamlūk prince ʿImād al-Dīn Ismāʿīl (b. c. 725/1325). However, since this prince was still an infant in 1327, the true dedicatee must have been his father, the reigning Sultan al-Malik al-Nāṣir Muḥammad ibn Qalāwūn (reg. 693-741/1293-1341, with interruptions). Ibn Jaydān claims that ‘the most deserving person concerning this science is the sultan … for his dream is truer and more veracious than [that of] all [other] people after the prophets’ (Or 7733, f. 4r, lines 10-13), and indicates that he had also dedicated other writings on dream interpretation to al-Nāṣir Muḥammad.

The all-but-forgotten Ibn Jaydān seems to have been al-Nāṣir Muḥammad’s personal dream-interpreter (muʿabbir), or he at least repeatedly sought this sultan’s patronage. Al-Nāṣir Muḥammad ruled over a relatively stable political climate, his third reign lasting thirty-one years, during which Ibn Jaydān wrote the Full Moon. It is not surprising therefore that Ibn Jaydān wrote in support of the Sultan’s dynasty, the Qalāwūnids (678-784/1279-1382). In his preface, Ibn Jaydān stresses the crucial role dream-interpreters played in foretelling and protecting a ruler’s lineage. He presents a series of examples where dream-interpreters correctly predicted the deaths of presumptive heirs to the throne and the births of future rulers. These stories served to remind al-Nāṣir Muḥammad of both the importance and reliability of dream-interpreters in foretelling the fortunes of ruling dynasties.

This context is key to understanding Ibn Jaydān’s dedication of the work to an infant prince. ʿImād al-Dīn Ismāʿīl was only one or two years old when Ibn Jaydān presented his dream interpretation manual, and was not necessarily the heir apparent. His half-brother, al-Malik al-Manṣūr ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn ʿAlī, as first son of al-Nāṣir Muḥammad’s first marriage, had been heir to the throne until he died aged seven and was buried in his father’s royal mausoleum in 710/1310. Ibn Jaydān refers to the late crown prince as ‘the martyred ruler ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn ʿAlī’ (ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn ʿAlī al-malik al-shahīd, Or 7733, f. 6v, line 13), and appears to have correctly predicted that ʿImād al-Dīn Ismāʿīl would one day become sultan. Indeed, he lived to reign as al-Malik al-Ṣāliḥ (reg. 743-6/1342-5). Ibn Jaydān’s dedication of the Full Moon to ʿImād al-Dīn Ismāʿīl would not only have been a vote of confidence in the viability of the prince’s future reign and thus the continuation of the Qalāwūnid dynasty, but also a statement of loyalty to the Sultan.

Conspiracies and Child Sultans

When the long and relatively stable reign of al-Nāṣir Muḥammad came to an end with his death, the subsequent forty-one years witnessed twelve of his descendants take the throne before the Qalāwūnid dynasty ended with the accession of al-Malik al-Ẓāhir Barqūq in 784/1382. Between al-Nāṣir Muḥammad’s death and the accession the following year of Ibn Jaydān’s dedicatee, al-Ṣāliḥ Ismāʿīl then about seventeen years old, no fewer than three of his brothers assumed the sultanate then either died or were deposed in factional intrigues. These tumultuous final years of the Qalāwūnid dynasty were dominated by the short reigns of very young sultans – often legal minors. Meanwhile, powerful Mamlūk amīrs wrestled for power as kingmakers and regents.

One of these young sultans was al-Nāṣir Muḥammad’s grandson, al-Malik al-Ashraf Shaʿbān II (b. 754/1353, reg. 764-78/1363-77). He was only ten when he became sultan, but held an uncharacteristically long reign for the period. In the early years, the real power was wielded by his regent and Commander-in-Chief (atābak al-ʿasākir), the “slave-soldier” (mamlūk) Yalbughā al-Khāṣṣakī. Three years after al-Ashraf Shaʿbān’s accession, the child sultan conspired with a group of six amīrs to overthrow Yalbughā and had him murdered in Rabīʿ II 768/December 1366.

In the ensuing turmoil, one of the six conspirators, the amīr Sayf al-Dīn Asandamur al-Nāṣirī (d. 769/1368) consolidated his power, winning military victories first against mamlūks formerly owned by and still faithful to Yalbughā and then against the Sultan’s own supporters. By the summer of 768/1367, Asandamur al-Nāṣirī had himself assumed the title of Commander-in-Chief, a position second in rank only to the Sultan. As regent, he was now master of the Cairo Sultanate and the power behind the throne of al-Ashraf Shaʿbān, who was only just coming of age at around fourteen years old. In this powerful position, he too seems to have turned to astrology for answers.

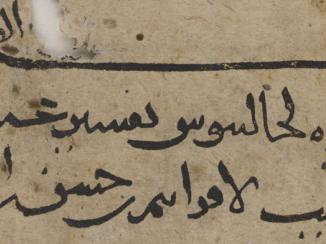

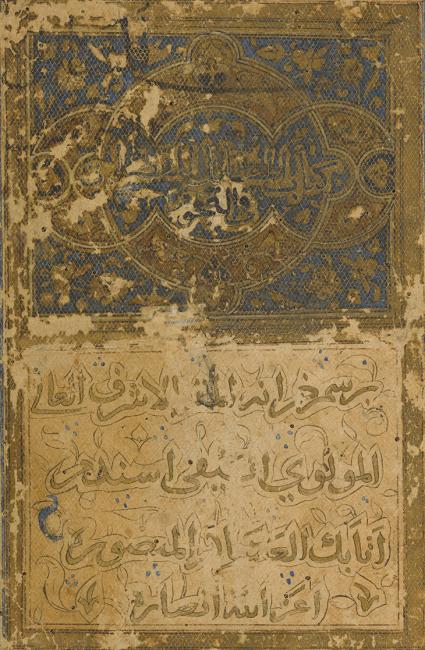

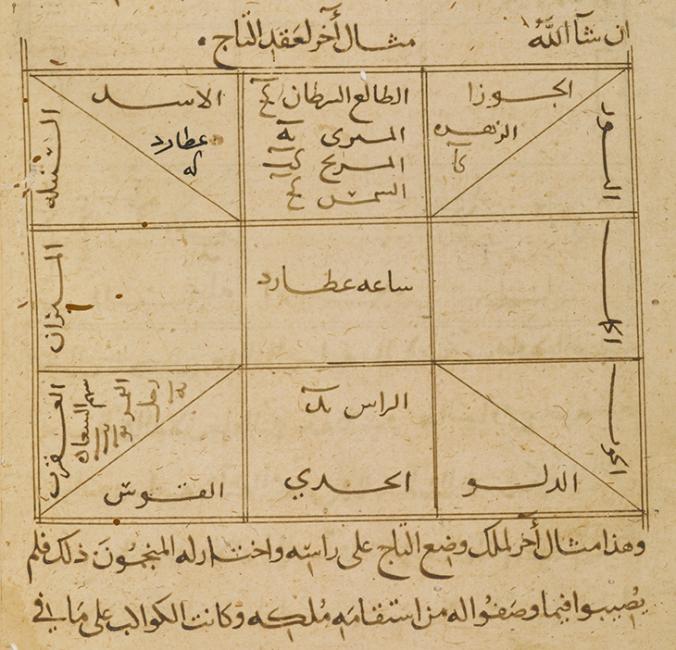

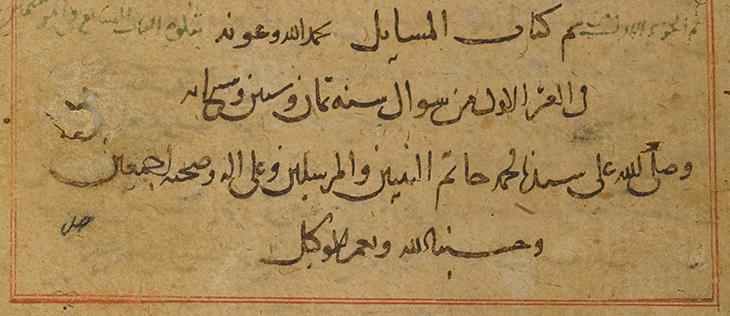

Asandamur’s Consolidation and Defeat: The Book of Interrogations

It may seem surprising that, during his dramatic rise to power, Asandamur al-Nāṣirī found time to consult a copy of the Book of Interrogations (Kitāb al-masāʾil) by the late third/ninth-century astrologer Abū Yūsuf Yaʿqūb ibn ʿAlī al-Qarshī al-Qaṣrānī. The text is a multi-volume treatise on ‘interrogations’, an astrological practice in which a question is answered by means of a horoscope cast for the time and place the interrogator poses the question. Since this practice was commonly used to predict the political fortunes of newly enthroned monarchs, and al-Qaṣrānī’s Book of Interrogations contains many historical examples of such royal horoscopes, it is not difficult to imagine why such a book appealed to Asandamur al-Nāṣirī as he consolidated his power.

Asandamur al-Nāṣirī’s copy of the Book of Interrogations (Delhi Arabic 1916 vol 1) was completed during the first ten days of Shawwāl 768/late May-early June 1367, just as he was defeating the Sultan’s forces to achieve total dominance over the Mamlūk sphere. We do not know if Asandamur al-Nāṣirī or an astrologer under his patronage actually used the techniques taught in the Book of Interrogations to foretell what would become of the new master of Egypt and Syria. Regardless of any astrological support, though, Asandamur al-Nāṣirī’s regency was short-lived. In Ṣafar 769/October 1367 his troops suffered a catastrophic defeat by those of the Sultan. Asandamur al-Nāṣirī fled to Alexandria, where he met his end shortly after in obscure circumstances.

Thanks to Prof. Jo Steenbergen (University of Ghent) for his help.