Overview

Today’s technology is shrinking. Less than fifty years ago computers were so big whole offices were needed to hold them. Now a laptop computer can fit in a rucksack, a tablet in your pocket and powerful computers are found in mobile phones. There is a race to produce smaller and smaller technology.

But this was not always the case. There was a time when bigger was better, as some of the most extraordinary Arabic manuscripts show.

Cymbals, Whistling Birds and a Gorgon’s Head

Imagine a clock around sixteen feet tall and comprising men on rods that rise and fall to indicate the hour. This clock is not short of mechanical decoration. In front of you is a tree full of whistling birds menaced by snakes that emerge from two caves, a playing flautist, a dial that indicates the month and a bird’s head that drops a ball onto a cymbal A percussion instrument consisting of thin round plates. once per hour. And that is before you see the robotic statues of bound captives, one of whom has his head cut off by a mechanical executioner each hour. To add to the threatening scene, the clock is replete with the head of the Gorgon Medusa whose eyes change colour on the hour.

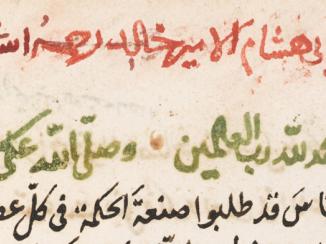

This extraordinary vision is the result of combining all the clocks described in the earliest and most influential Arabic text on water-clocks. The work is attributed to Archimedes (c. 250–212 BC), but the ‘Book of Archimedes on the Construction of Water-Clocks’ (Kitāb Arshimīdas fī ʿamal al-binkāmāt is most likely a ninth-century compilation of a number of short works by authors writing in Greek, Persian and Arabic.

Monumental Hydraulic Machines

The water-clocks (Ar. binkām Water Clock in the Arabic sources. , pl. binkāmāt) of the ancient and medieval Mediterranean world were monumental, hydraulic machines first used to tell time, but later designed to display astronomical information such as the phase of the moon and positions of the planets and stars.

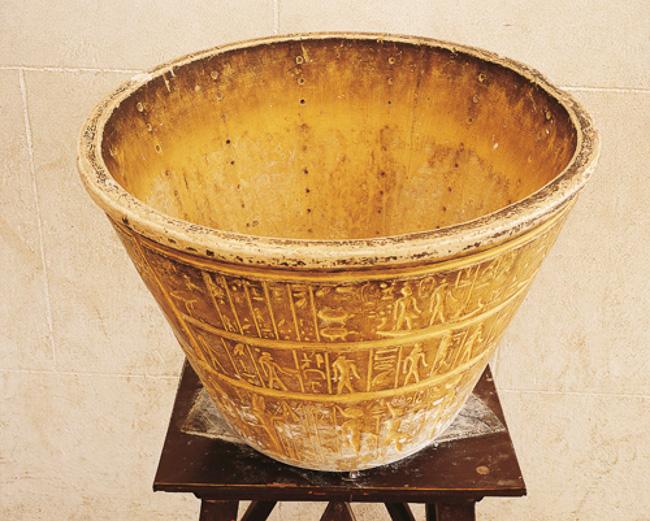

No-one knows when the first water-clocks were used, and traces of them have been found amongst the early remains of the civilisations of Egypt, Babylon, India and China. The earliest water-clocks were simple devices consisting of a conical bowl with a hole pierced in the bottom of its side, near the base.

The bowl was filled with water, which was allowed to drip from its hole. The time taken for the water to drip from the bowl was measured with a sundial and lines could be made on the inside of the bowl to mark the passage of hours and subdivisions of hours.

Such a bowl, or clepsydra A greek word for a water clock, literally meaning water thief. (lit. ‘water thief’) as the Greeks called it, was an accurate time-keeper and had a distinct advantage over the sundial. Unlike the sundial it was useful at night, indoors, on cloudy days and at other times and places where the sun was not visible.

From Dripping Bowls to Elaborate Monuments

Over the centuries from the Classical period (c. fifth century BC) to Byzantine times in the middle ages, the Greeks developed clepsydrai to perform more and more elaborate functions, adding a vessel to catch the dripping water, which raised a float and a pointer indicating the correct time.

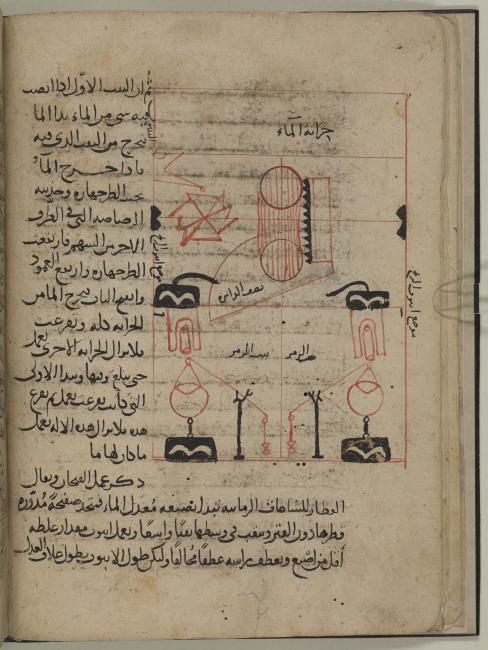

Later they added gears, chains, pulleys, various water-tanks, floats, air-tanks, water-wheels and even mechanical celestial spheres, animals and people. These more elaborate clocks are what we mean today when we refer to water-clocks, and the Arabs of the golden age of Islam excelled at designing and building them.

The Arabs probably inherited their initial knowledge of water-clocks from those they had seen standing in Persian and Byzantine lands. The city of Gaza, for example, had an elaborate monumental water-clock in a central square that was still fully functional in the sixth century AD.

Water-Clocks in Arabic

The Archimedes text and others like it were read by such authors as the [4]Banū Mūsá[/4] brothers in ninth-century Baghdad and al-Jazarī (active 1181–1204) in eastern Anatolia South-east Turkey today. (now south-east Turkey). You can see the influences of the water-clock ascribed to Archimedes in Jazarī’s ‘Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices’ (Kitāb fī maʿrifat al-ḥiyal al-handasiyah.

Although the clocks described in these books may seem over the top by today’s standards, they were the most accurate time-keeping devices known before the first pendulum clocks were built in the seventeenth century by the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens (1629–95).