Overview

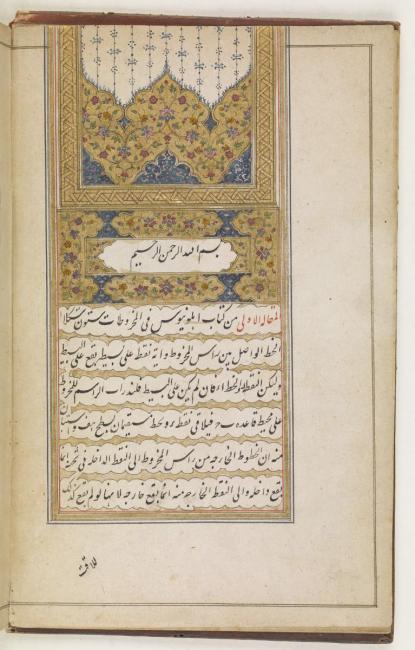

During the first four centuries of Islam (the sixth–tenth centuries AD), almost all the Greek scientific and philosophical literature available in manuscripts was translated into Arabic, along with many similar texts in Syriac, Persian and other languages.

This was such a monumental task and demanded such a concerted effort it has become known as the ‘translation movement’. Translation did not simply cease after the tenth century, but by around the end of the tenth century the task of translating pre-Islamic scientific and philosophical texts from Greek, Syriac and Persian was for the most part complete.

Baghdad, Paper and the Translation Movement

The translation movement began in earnest during the reign of al-Manṣūr, the second ʿAbbāsid caliph (reg. 754–75 AD). This coincides with two other events that were vital to the survival of the translation movement: the transmission of the art of papermaking into the Islamic world by Chinese artisans in 751 AD, and the foundation of the grand capital Baghdad by al-Manṣūr in 762.

This vibrant and thriving new city that straddled the old boundary between East and West was home to a multilingual population from all over the Islamic world and beyond. The new medium of paper, produced for the first time within the Islamic world, provided further impetus for literature and the book trade. In fact, the same cultural tendencies that produced the translation movement also produced a general boom in the production of books and cultivation of reading that has been called the Arabic ‘cult of books’.

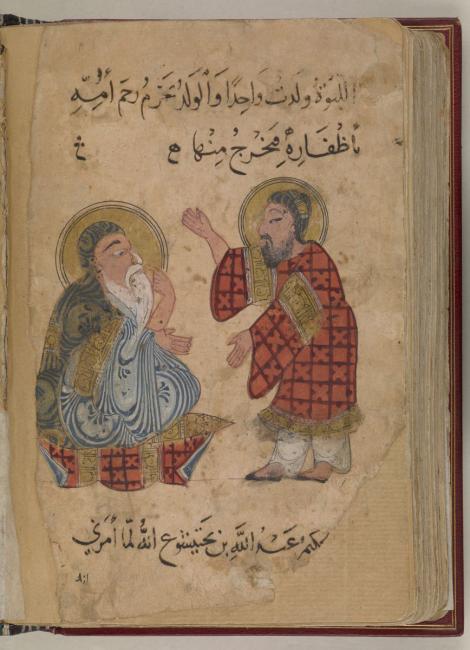

Jūrjīs ibn Bakhtīshū‘ and al-Biṭrīq

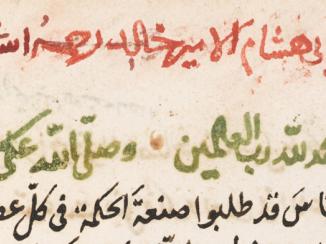

Some of the earliest translators involved in the translation movement at the time of al-Manṣūr were Jūrjīs ibn Bakhtīshū‘ and al-Biṭrīq. Jūrjīs ibn Bakhtīshū‘ (fl. mid-seventh century) was al-Manṣūr’s court physician, and a Nestorian Christian from Persia, who spoke Persian and Syriac; al-Biṭrīq was a Melkite Christian, who spoke Syriac and Greek. Both produced translations of scientific texts for al-Manṣūr. Both men also shared certain characteristics with other such translators. Four of the characteristics were common amongst many translators of the period: they were multilingual, speaking Syriac, Persian and Greek; they were Christians; they enjoyed patronage from a wealthy and politically important figure; and, in the case of Jūrjīs ibn Bakhtīshū‘, they were practicing men of science, too.

Dynasties of Scientists and Translators

Another feature they shared with other translators of the period was that scientific study and translation was a family business for them. Jūrjīs ibn Bakhtīshū‘ was the first in a line of court physicians to the caliphs that spanned six generations and lasted almost three centuries and al-Biṭrīq’s son, Ibn al-Biṭrīq followed in his father’s footsteps as a translator.

Likewise, the famous translator and physician Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq (d. 873) was joined in his translation work by his nephew Ḥubaysh and his son Isḥāq ibn Ḥunayn (d. c. 910), who specialised in translating mathematical texts. A dynasty of scientists and translators lasting at least four generations was also started by the pagan mathematician Thābit Ibn Qurrah from Ḥarrān (d. 901). His son was the mathematician, astronomer and physician Sinān ibn Thābit (d. 943), his grandson the mathematician and astronomer Ibrāhīm ibn Sinān (d. 946), and his great-grandson the physician and translator Thābit ibn Ibrāhīm (d. 980).

Patronage of the Banū Mūsá

Both Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq and Thābit ibn Qurrah were highly valued for the accuracy and style of their translations. Both men translated under the patronage of the rich and influential Banū Mūsá. The Banū Mūsá were three brothers, sons of Mūsá ibn Shākir, a bandit turned astronomer and friend of al-Ma‘mūn, the seventh ‘Abbāsid caliph. These brothers, who were renowned astronomers, mathematicians and engineers in their own rights, also sponsored scientific translations by paying translators monthly salaries. The best translators, like Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq and Thābit ibn Qurrah, are reported to have earned the enormous sum of five hundred gold dinars a month for their efforts.

These translators were highly trained, multilingual scientists who passed their skills down the generations, and their patrons were rich and well-connected, often in positions of great political power. This combination of scientific and linguistic competence and high-level patronage ensured the translation movement produced vast amounts of extremely accurate and readable translations of the most important scientific texts of the pre-Islamic world.