Overview

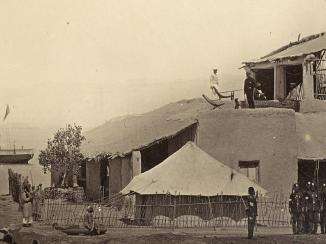

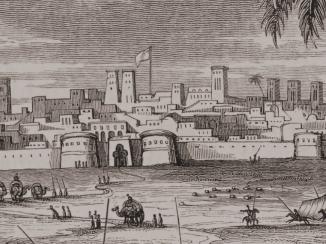

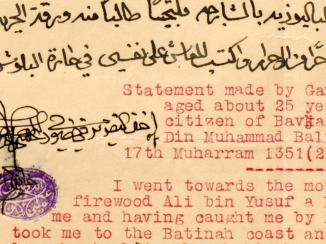

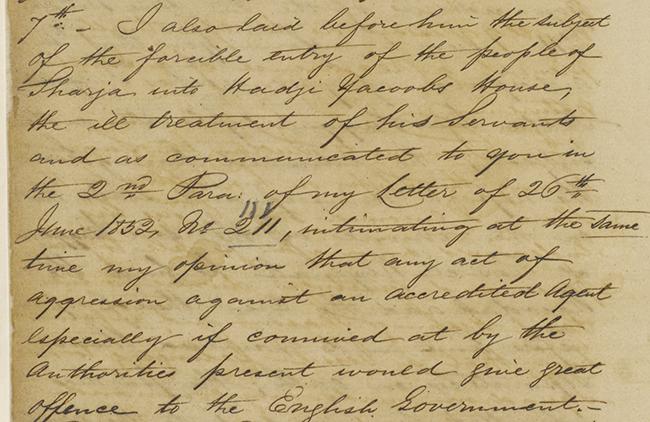

In August 1852, the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , Captain Arnold Kemball, reported to the Government of India of abuse directed at the Sharjah Native Agent Non-British agents affiliated with the British Government. , Hajji Yaqoob, and towards his servants. Apparently at the instigation of the town’s governor, the abuse was perpetrated by a number of Sharjah’s inhabitants.

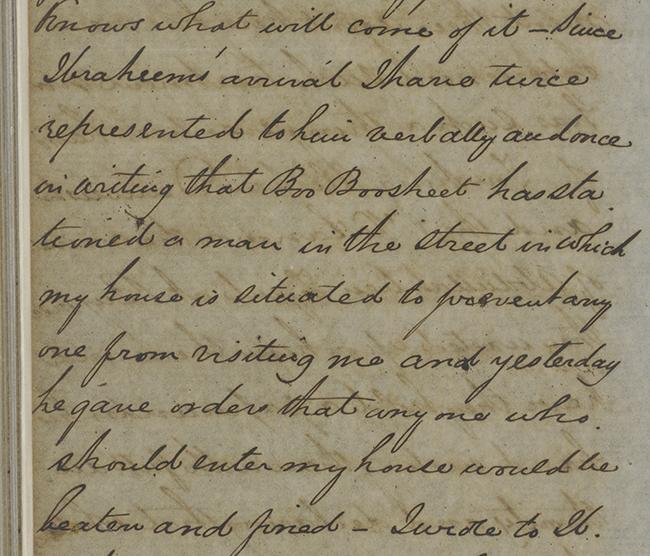

Less than one year later, in July 1853, Yaqoob encountered further ignominy when a number of men burst into the majlis of his house, beat his guests and threatened him, demanding that he leave the country. And, in 1863, the Arabic scholar William Palgrave, in spite of confessing that he hadn’t actually met Yaqoob in person while passing through Sharjah, felt compelled to cast aspersions on the native agent’s dealings.

Anger and prejudice, though probably not a reflection of the day-to-day sentiments Yaqoob encountered in Sharjah, do reveal much about the attitude of others towards him. Yaqoob’s status as an Armenian immigrant from Basra should not have been sufficient to foster such ill-feeling amongst the inhabitants of Sharjah. After all, the towns of the Arab coast were characterised by their mix of indigenous Arabs, Persians, Hindu merchants and members of the Jewish and Armenian diasporas.

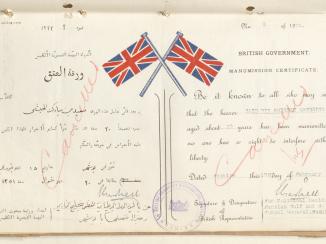

Instead it was Yaqoob’s status as a British Agent, or – as he described the accusation of those who stormed into his house in 1853 – ‘an Agent of the Christians’, that likely aroused the greatest suspicion amongst those surrounding him. It was widely understood that the principal reason for Yaqoob being in Sharjah was to spy on and inform the British authorities of any incidents of slave trading and piracy that he became aware of. It was on this count that Palgrave questioned Yaqoob’s morals, suggesting that he was as likely to turn a blind eye to the sale of a slave as he was to inform his superiors at Bushire.

But Yaqoob’s status as a British Agent also afforded him protection, to the extent that even the mildest acts of violence reported against him were likely to incur the wrath of the Resident, and cause a man-of-war to appear off the coast in the days that followed.

Yaqoob’s predicament was not unique, for the role of Britain’s Agent at Sharjah was an incessantly thankless one for most of the time. The ruler of Sharjah reputedly had nothing to do with the first Native Agent Non-British agents affiliated with the British Government. in the town, while another of Yaqoob’s predecessors, Moollah Hussain, could only gain the confidence of the ruler’s brother, but not the ruler himself.

It was not until the 1920s, after the appointment of ‘Isa bin ‘Abd al-Latif, that the position of Native Agent Non-British agents affiliated with the British Government. at Sharjah became associated with considerable power and influence. For al-Latif’s predecessors, the role was a challenging one, in which the incumbent had to walk a fine line between the interests of his British employers, and those of the people he lived amongst.