Overview

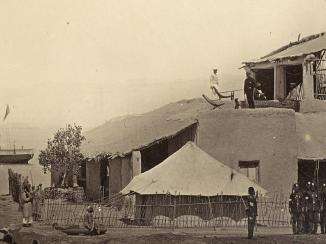

In late April 1820, Lieutenant Thomas Lumsden of the Bengal Horse Artillery stayed as a guest of the Resident, William Bruce, at the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. in Bushire, Persia, while on his long voyage back to London. On 24 April, Lumsden wrote in his diary of a ‘disgraceful proceeding’ that had taken place at the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. , in which an African crewman, who had been flogged on board his ship, had died. Three days later, Lumsden and his fellow travellers departed from Bushire on the backs of four mules, and likely never gave another thought to the African who had died in their presence again.

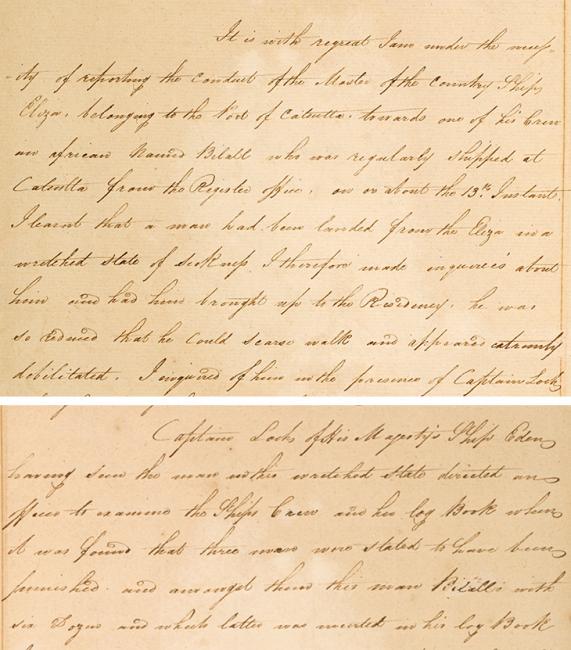

Bruce, by contrast, had to deal with the consequences of the tragic event. His letters to the Governor in Council in Bombay suggest genuine concern for the plight of the crewman, whose name was Bilal. Writing shortly after Bilal’s arrival at the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. , and in spite of him being in ‘such a state that Doctor Dow A term adopted by British officials to refer to local sailing vessels in the western Indian Ocean. [the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. surgeon] expects him to die’, Bruce wrote that he had comforted the sick man by telling him he should be taken care of and returned to India ‘to get redress for any wrongs he might have received’.

‘Six-Dozen Lashes’

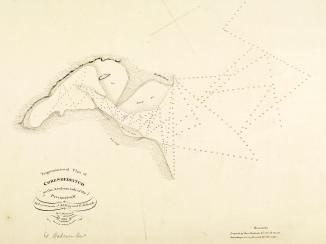

The enquiry that followed in the wake of Bilal’s death threw up findings that appeared to contradict themselves. According to the logbook of Bilal’s vessel, the Eliza, on 5 March 1820, the ship’s captain, Mr Woodhead, ordered Bilal to be lashed seventy-two times as punishment for attempting to desert ship at Bahrain. Bruce also learnt that, after the punishment, Bilal ‘sulked’, and that no more work could be got from him, which led to further beatings. As a result of Bilal’s condition worsening, Woodhead made the decision to offload the sick man at Bushire on 13 April, where he was handed over to the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. ‘in a wretched state of sickness’.

However, Doctor James Dow’s post mortem, the results of which were recorded in a letter sent from the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. to Bombay, stated that there were ‘no marks of violence of any kind’ on the sailor’s body, and that ‘a sudden attack of dysentery terminated his existence’.

Cruelty Widespread on ‘Country’ Ships

The lack of evidence of the violence used against Bilal appeared to undermine the possibility of further official investigation, but Bruce was not prepared to let the matter lie. In a further letter to Government, dated 26 April, Bruce hoped that the ‘Honourable Board […] will see the necessity of having Mr Woodhead called to severe account in the present case, as attaining an example to others. As I am sorry to say that the treatment on board merchant ships which visit the Gulf is too often what it ought not to be towards their crews.’

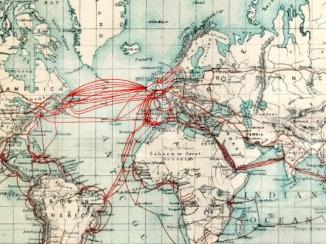

The crews of the merchant (‘Country’, or ‘Bombay Country’) ships that plied the seas around the Indian Ocean were composed of a diverse mix of men. While the officers were European, their crews were dominated by Africans (frequently referred to by the British as sedees, or sidis), and Indians ( lascars A term used by the British officials to describe non-European sailors employed on East India Company ships. ). More often than not the treatment of these crewmen by their officers was unnecessarily cruel, and the punishments meted out were not always entered into the ship logbook.

There is ample historical evidence of such cruelty. For example, two American missionaries who travelled to India in 1838 remarked that the crews of the country ships ‘were gathered from every nation and tribe in the East’, and were ‘indolent in the extreme’, the consequence being that ‘the officers beat them without mercy’. Bruce’s own further investigations in the wake of Bilal’s death found further evidence of the violence that was meted out on the Eliza. In June 1820, he wrote to Government, describing further claims against the Eliza’s masters, including one relating to the ship’s gunner and ‘seacunnee’ (seacunny, or steersman), who had ‘a violent swelling over one eye’, which ‘the chief officers had given to him by knocking him down with a billet of wood’.

‘Proper and Correct’

In spite of the claims Bruce eventually had to the accept that ‘Captain Woodhead [had] proved to the satisfaction of the Senior Magistrate of Police and Honourable Company’s solicitor that his conduct has been proper and correct’. The inquiry into Bilal’s death went no further.

The preponderance of violence against native crews on Country ships endured until the mid-nineteenth century, when the increasing prevalence of steam-powered ships reduced the need for skilled seaman. In the meantime, for many crews the sole recourse to justice appeared to be violent mutiny against their officers. ‘Many times a year’ the American missionaries on their way to India noted, ‘this mournful tragedy is acted over in one or more of the country ships’.