Overview

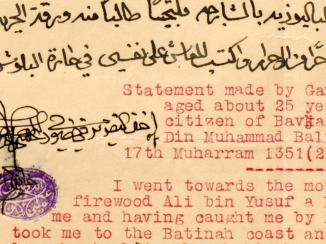

On 11 June 1910, Abdul Rahim bin Ahmad arrived with twenty-two of his compatriots in Bahrain on the steamship Waroonga, from Bandar-e Lengeh in Persia. Upon arrival, Abdul Rahim stated to officials at the Bahrain Political Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. that the Karguzar (Foreign Ministry representative) at Bandar-e Lengeh had charged him just two Persian Qirans (the equivalent of GBP 41 today) for each man to go to Bahrain as opposed to the twenty Qirans (GBP 414) payable for passage to Dubai and Muscat.

Abdul Rahim and his compatriots had, in other words, been charged the cheaper fee for passage between Persian ports, rather than the more expensive fee to foreign ports.

An Unequivocal Claim by Persia over Bahrain

Abdul Rahim further explained that he was also required to produce surety for the reduced fee, and that on arrival in Bahrain, he had to present himself to one Haji Abdul Nabi, a Persian resident of Manama, who would sign the passports on the authorities’ behalf.

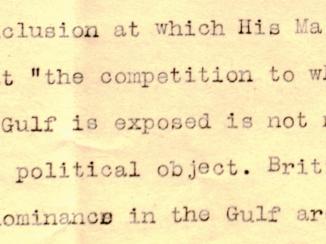

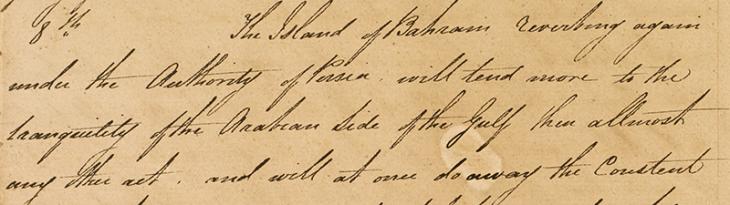

Abdul Rahim’s statement was proof of what British officials in the Gulf had suspected for a number of years – that some Persian officials were treating Bahrain as a Persian port, and issuing Persian travel passes accordingly. The British Government viewed such behaviour as an unequivocal claim by the Persian Government on Bahrain, and expressed their objections through diplomatic channels.

But the British were reluctant to disapprove too strongly. The question of Bahrain was a sensitive issue between the Governments of Persia and Great Britain, with a host of historic and contemporary issues adding subtle inflections to the situation.

Anglo-Persian Tensions and Diplomacy

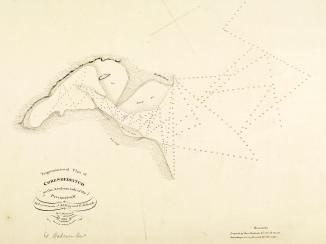

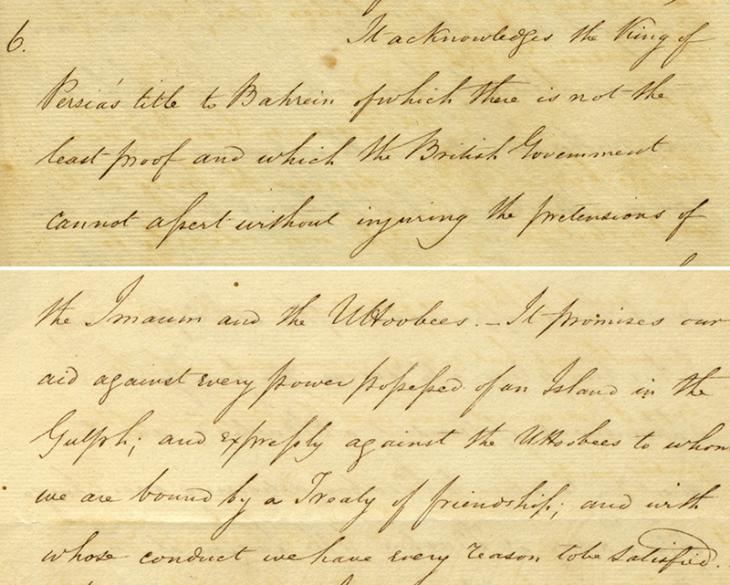

The history of Anglo-Persian tensions over Bahrain can be traced back to 1820, when Britain signed a maritime peace treaty with the Al Khalifah of Bahrain. Persia objected to Britain’s relationship with Bahrain, and began to reassert an historic claim over the islands. In 1822, the British Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. , Captain William Bruce, signed an agreement with the Persian authorities, which stated unambiguously that Bahrain was ‘always subordinate to the province of Fars’.

Bruce, who had concluded the agreement without consultation with the British authorities in India, was summarily dismissed from his post as Resident by his superiors at Bombay, and the 1822 agreement remained a point of contention between Persia and Britain for the next hundred years, with the former repeatedly insisting its validity, and the latter maintaining that the agreement had never been formally ratified, and as such was void.

In spite of disagreements over Bahrain, Britain and Persia continued to maintain largely cordial diplomatic relations. Britain maintained a diplomatic post at the Court of Persia, and continued to operate its Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. at Bushire. Moreover, in 1901, the Persian King Muzaffar al-Din Shah Qajar granted a British subject, William K. D’Arcy, a sixty-year oil concession, paving the way for the creation of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company.

British Establishment of a Political Agency in Bahrain

The British Government’s establishment of a Political Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. in Bahrain in the 1900s, roughly coincided with the constitutional revolution in Persia, which took place between 1905 and 1907. In 1906, Persia renewed its claims to sovereignty over Bahrain. In 1907, British officials became aware for the first time of domestic Persian passports being issued to Persians travelling to Bahrain.

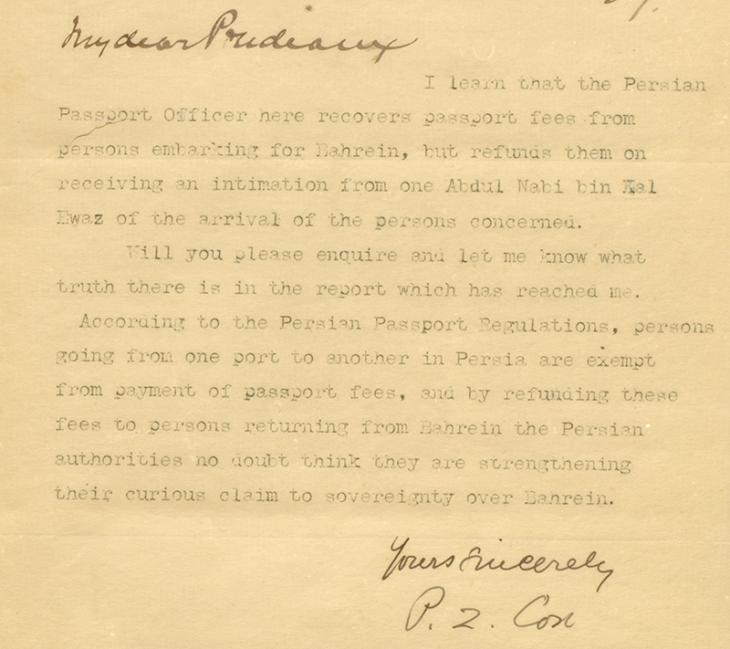

Three years later, Abdul Rahim’s statement confirmed these suspicions. British officials moved quickly to stop Haji Abdul Nabi ‘arrogating to himself the functions of a [Persian] consular or passport official’, which was, in the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. Sir Percy Cox’s own words, ‘highly objectionable’ to both the Shaikh of Bahrain and the British Government.

But in spite of the charges and objections, British officials remained reluctant to punish Nabi in any way that might upset the Persian Government – or Bahrain’s Persian majority. In the immediate wake of his actions being discovered, both the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. , Captain David Lorimer, and the Ruler of Bahrain, Shaikh Isa bin Ali Al Khalifah, agonised over how best to punish Haji Abdul Nabi.

Ultimately, both Lorimer and Shaikh Isa shied away from deportation, the former wishing to avoid making worse a domestic situation that was already ‘very involved and difficult’, and the latter preferring to keep his enemies close by. In lieu of deportation, a security was demanded of Nabi, as guarantee of his future good behaviour.

![Reçu d’amende [receipt of fine]. IOR/R/15/2/2, f. 100](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/vdc_100023043182.0x000013_cropped.jpg?itok=urNYAscM)