Overview

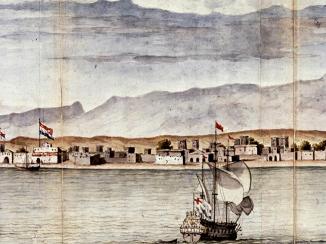

On 19 March 1938, Gerald de Gaury, the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Kuwait, wrote to Trenchard Fowle, the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. at Bushire, reporting that opposition to Shaikh Aḥmad al-Jābir Āl Ṣabāḥ, Kuwait’s ruler, had ‘crystallized’ following the public ‘flogging, etcetera, of one al Barrak’. Muḥammad al-Barrāk, who had been caught writing defamatory graffiti about Shaikh Aḥmad, was the leader of a strike by taxi drivers aggrieved by a ban on women travelling outside of the town alone. Such excursions were a source of regular income for the drivers. His beating and subsequent torture was a defining moment in what became known as Kuwait’s majlis movement.

A Decade of Discontent

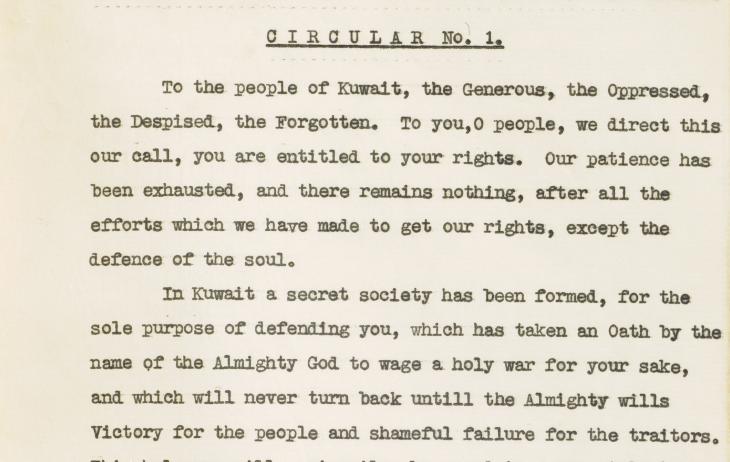

Opposition to Shaikh Aḥmad’s administration had been growing for some time. It was led by Kuwait’s prominent Sunni merchants, many of whom had migrated with the ruling Āl Ṣabāḥ family from Najd in the eighteenth-century, and factions of the Āl Ṣabāḥ themselves, headed by Aḥmad’s cousin, ‘Abdullāh al-Sālim. Their opposition was articulated through complaints about the administration – the uneven distribution of state revenue, the corrupt justice system, inadequate education and training, unfair municipal elections, and the Shaikh’s lifestyle and lack of contact with his people and family – and calls for the formation of an elected council (majlis).

Besides being an important development in Kuwait’s history and that of political reform in the Gulf as a whole, the majlis movement, and Britain’s response to it, also brings into focus the broader forces acting upon the region at the time. There were deeper reasons for the unrest in Kuwait. Economic hardship was certainly significant. The trade embargo Ibn Saud had imposed on Kuwait had lasted almost two decades, and the effects of the Japanese cultured pearl industry were also being felt through a slump in Gulf pearling prospects. With a global depression taking hold, the fortunes of Kuwaiti merchants had taken a turn for the worse.

Arab Nationalism and the Iraqi Connection

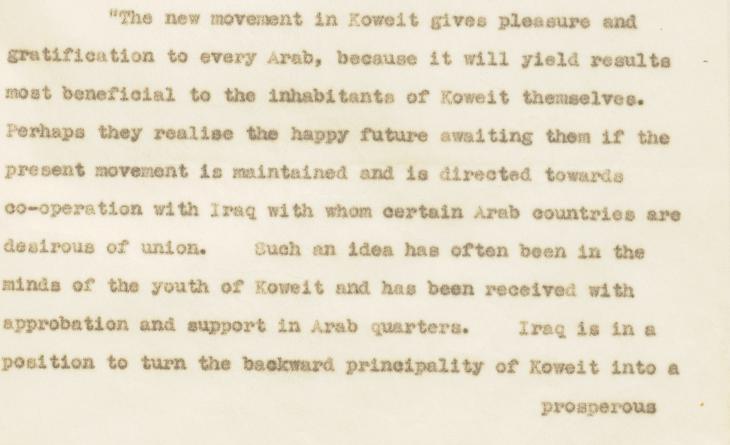

Around the same time as the al-Barrāk incident, articles began to appear in the Iraqi press in support of the majlis movement. Translations of such articles were regularly sent by the Political Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. in Kuwait to the Bushire Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. . Many of the articles called for the annexation of Kuwait by Iraq, claiming it to be an ‘Iraqi district’ that Iraqis ‘regard […] as part of their own country’. The historic roots of this claim lay in Kuwait’s former economic and administrative connection to the Ottoman vilayet (or province) of Basra. It was strengthened by the close relationship Kuwaiti notables had with the country, many owning land and with business and personal connections there.

The influence of Arab nationalism, which had risen to prominence following the carve up of the Middle East by Britain and France after the First World War, can be read in the Iraqi newspaper articles. In May, Al-Kharkh newspaper printed the sentiment that to leave Kuwait to ‘grope in the darkness of ignorance and misadministration’ would ‘pain the heart of every Arab’. A month earlier, Al-Istiqlal had called for Kuwaitis to ‘join in the general awakening movement’ and ‘participate in the wide field of national endeavour’. Broadcast from the urban centres of Beirut, Damascus, Jerusalem and Baghdad, these ideas were being received in Kuwait and other parts of the Gulf.

The British Response

Discontent was also fomented by what was perceived as growing British interference in Kuwaiti affairs, particularly control of foreign relations and immigration. This evoked a response from the British, who, mindful of the power the Arab nationalist movement could have, moved to safeguard their own interests in the country, particularly that of oil. Their reaction is an example of how a careful manipulation of local forces could serve imperial interests by preventing unwanted change from without.

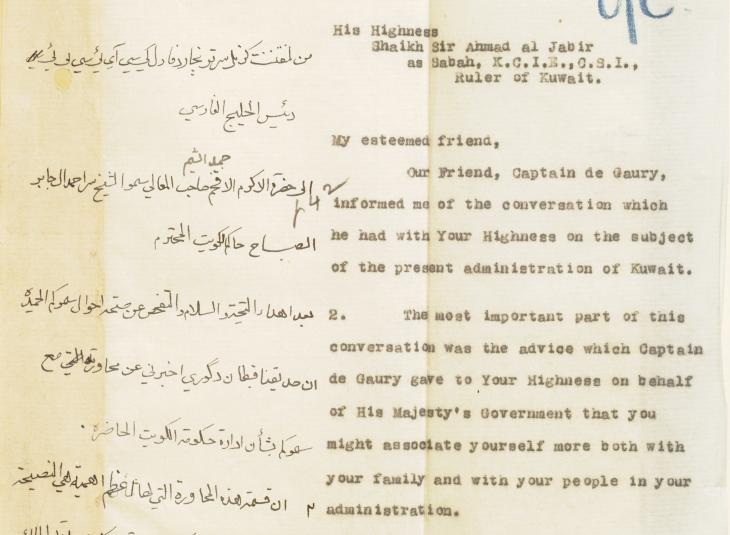

In June, Fowle wrote to Shaikh Aḥmad, advising him to form a council, as demanded by the dissidents. The best way to deal with such movements, he believed, was with ‘a sympathetic guidance of the movement into useful channels of activity’. When Shaikh Aḥmad finally agreed to the council in early July, however, it was more of an elected executive than the advisory body Fowle had hoped for. When the council took an interest in oil, Britain feared for their concessions and began to back Shaikh Aḥmad once more.

The council did not last long. Aḥmad dissolved it for good in March 1939, but it had ceased to be effective from the previous December, when Fowle wrote that the ‘balance of power as between Sheikh and Council has been readjusted in favour of the former which suits us’. Despite its failure to achieve political reform, the majlis movement was among the first of its kind in the Gulf. The events of 1938 also help to place Kuwait within the broader Middle Eastern context. The documents of the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. also make clear how British imperialism responded to these regional developments.