Overview

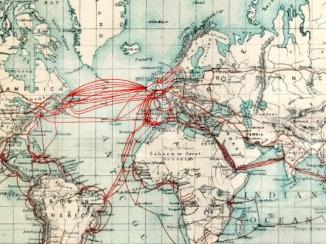

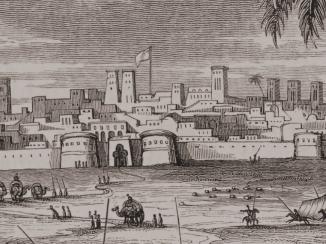

At the beginning of the twentieth century, after three decades of unprecedented growth, Germany’s economy threatened to overhaul those of her closest European rivals, Great Britain and France. While Germany did not possess colonies to the same extent that Britain and France did, her economic and political influence stretched a long way beyond the corridors of power of the German Government in Berlin. That influence reached as far as Persia and the Arabian Peninsula, via the steamships that plied their trade from Hamburg and along the railway line being constructed from the German capital to Baghdad.

A Lucrative Industry

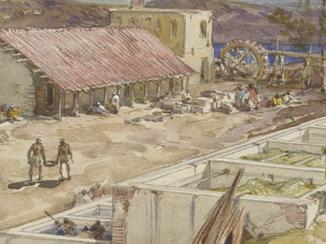

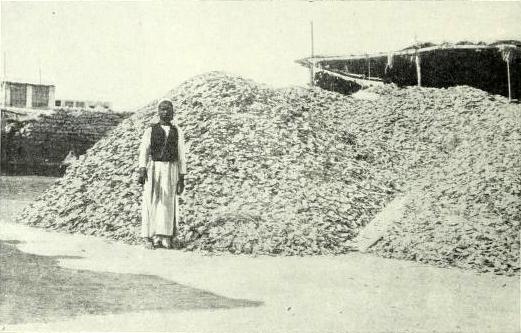

The Gulf’s lucrative pearl industry, estimated to be worth over £260,000 in 1900 (or nearly £24 million in present-day terms) had not escaped German attention. The German businessman Robert Wönckhaus opened offices in a number of ports on the shores of the Gulf between 1899 and 1906, at Basra, Bandar-e Lengeh and Bahrain. Wönckhaus’ chief interest was in mother-of-pearl (or nacre, obtained from the oyster shells that were otherwise disregarded) which had become increasingly popular in Europe.

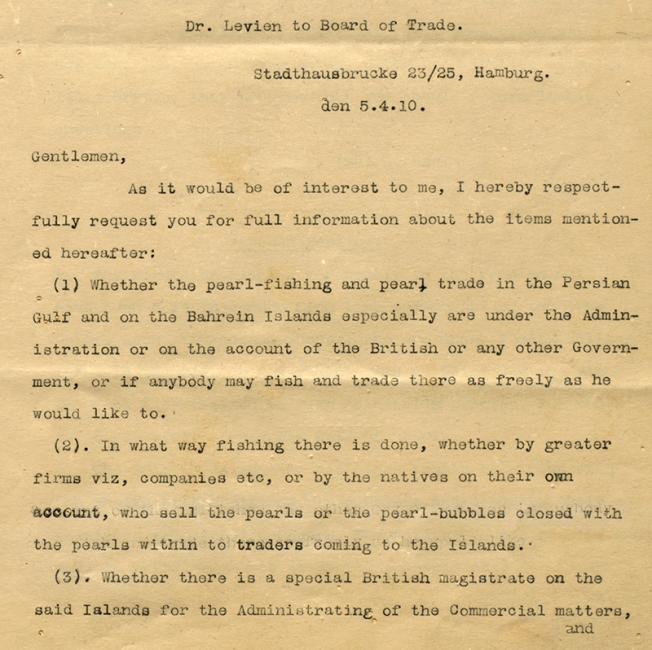

The British Government was sensitive to foreign interest in the Gulf’s pearls – especially sensitive when that interest came from Germany. Correspondence shows that an enquiry made to the British Government about the Gulf’s pearl industry from one Doctor Levien of Hamburg in 1910, provoked the admission from a Foreign Office official that the industry in the Gulf was ‘really more political than commercial’, and especially so in Bahrain.

A German Spy in Bahrain

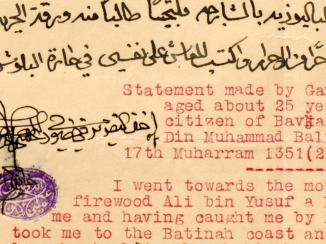

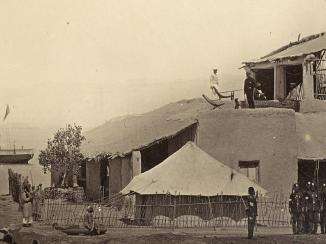

After the outbreak of war in Europe in August 1914, British officials scrutinised German commercial activity in the Gulf even more closely, suspecting that German merchants might be secretly working as intelligence agents for their Government. When they searched the Wönckhaus offices in Bahrain in November 1914, they discovered papers describing British troop movements in the Gulf. Herr Harling, the Wönckhaus representative in Bahrain, and the author of the discovered reports, was swiftly despatched by British officials to a prisoner of war camp in India.

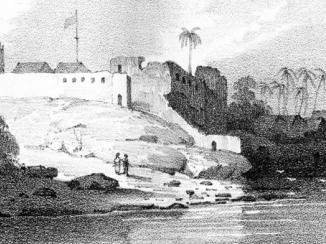

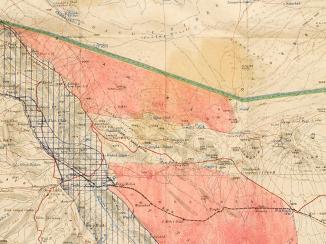

By mid-1918, the balance of power in Europe was now favouring the Allies, and the situation for Germany was turning increasingly bleak. Any commercial or strategic interests that Germany (and their Turkish allies) had held in the Gulf were gone. This included Qatar, whose Turkish garrison had departed in 1916, in the wake of which, Shaikh ‘Abdullāh bin Jāsim Āl Thānī signed a treaty of protection with Britain’s Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. , Percy Cox.

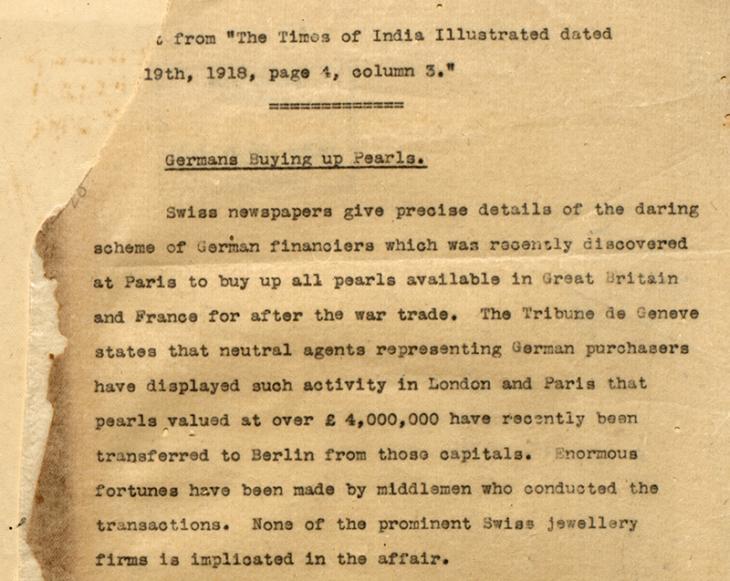

German officials did not, however, forget the great value of the Gulf’s natural pearls. In June 1918, rumours in Europe and the Middle East circulated that German financiers were attempting to buy up as many pearls available on the British and French markets, probably in an effort to shore up an economy that was falling into tatters after four years of war.