Overview

Curzon, Persia, and the Gulf

From early in his political career, George Curzon believed that maintaining and extending British influence in Persia [Iran] and its surrounding region, including the Gulf, was strategically vital to the protection of British rule in India. Later, as Viceroy of India, Curzon encouraged British trade in Persia and visited the Gulf himself in 1903. However, Curzon was also interested in Persia more generally and spent several months touring the country from late 1889 to early 1890. He made the trip as a correspondent for The Times, writing several articles on Persian political affairs. As Curzon noted later, he ‘profited by the opportunity to collect a great deal of additional information’, which, together with the research he had already amassed, formed the basis of his book Persia and the Persian Question (Mss Eur F111/33, f. 58r).

An Ambitious Undertaking: Persia and the Persian Question

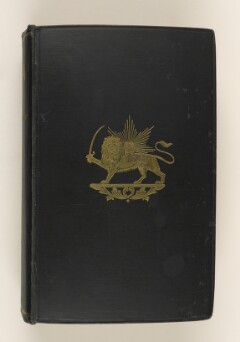

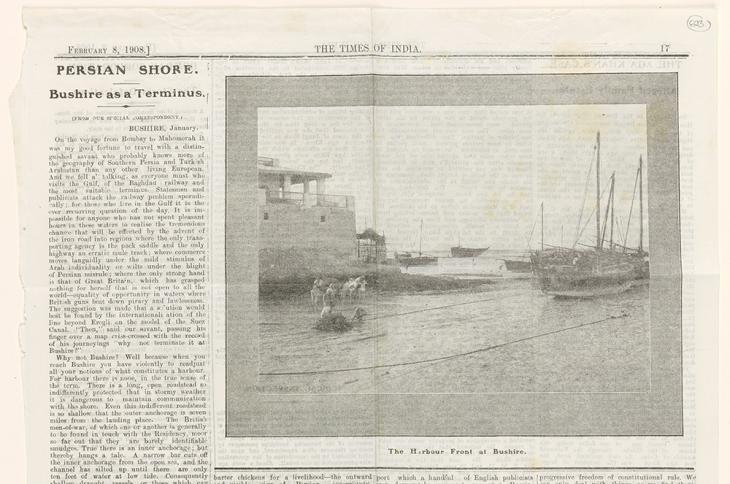

Published in two volumes in 1892, Persia and the Persian Question was and remains an ambitious and arguably hubristic attempt to document Persia’s history, archaeology, and topography, albeit from the orientalist perspective of someone deeply invested in the British imperial project. As Curzon writes in the introductory chapter, his book aims to ‘present a full-length and life-size portrait’ of Persia (Mss Eur F111/33, f. 69r). A glance at the titles of the book’s thirty chapters reveals its wide-ranging scope, listing the country’s capital Tehran, its various provinces, its historic sites, its ruling Qajar dynasty, the Gulf, and numerous subjects including government, army, navy, railways, and trade and commerce as the main topics of discussion. The book contains several maps and many illustrations, including prints of photographs, some of which Curzon took himself during his travels.

While covering a range of subjects, Persia and the Persian Question also has a very specific focus. As Curzon notes in the preface, ‘the primary object of this work may be described as political’, with the titular ‘Persian Question’ almost certainly referring to the country’s strategic importance in Britain’s ‘Great Game’ against rival imperial powers, most notably Russia (Mss Eur F111/33, f. 59r). In his opening chapter, Curzon refers to Persia as one of several ‘pieces on a chessboard upon which is being played out a game for the dominion of the world’ (Mss Eur F111/33, f. 68r). Fittingly, the final chapter is dedicated to British and Russian policy in Persia.

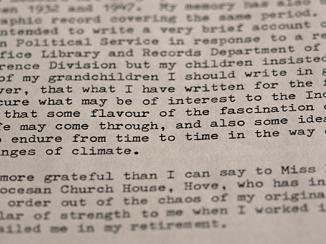

Curzon’s preface provides further insights into his intentions for writing Persia and the Persian Question and his wishes for its reception. In one passage, he expresses his hope that the book will become ‘the standard work in the English language on the subject’ (Mss Eur F111/33, f. 58r). Later, however, he also acknowledges that the writing of such an extensive work inevitably entails ‘the commission of some blunders and mistakes’ and invites his readers to assist him in applying any necessary amendments to a future edition (Mss Eur F111/33, f. 61r). This suggests that Curzon may not have been entirely satisfied with the book. Further signs of this are evident in some of his private papers Documents collected in a private capacity. .

Preparing for Revisions

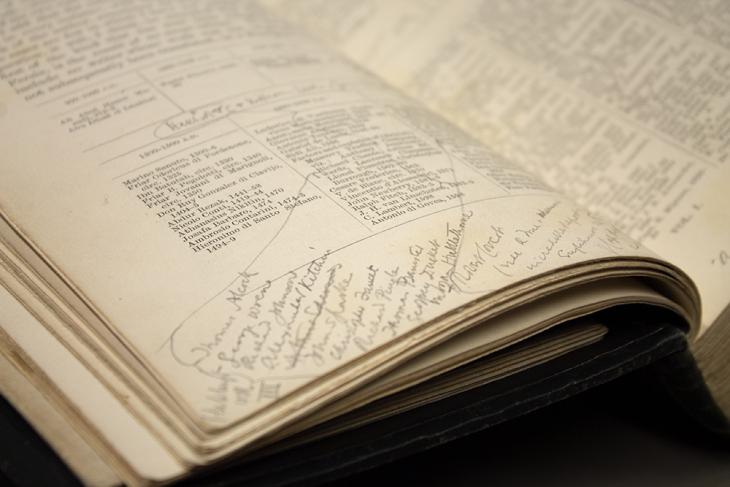

An entire series within Curzon’s vast collection of private papers covers the writing and publication of Persia and the Persian Question (Mss Eur F111-112 Series 123). Draft manuscripts of large parts of the book are included, along with related correspondence, newspaper cuttings, maps, and reports. Also present is a volume of notes and printed papers that Curzon collected at the time of the book’s publication, presumably with a view to preparing a revised edition. Further evidence of Curzon’s intention to revise the work is present in his own personal copy, which contains his numerous handwritten annotations, as well as even more revealing insights into how unfinished he considered the book to be.

Curzon’s personal copy of Persia and the Persian Question also contains dozens of assorted papers, seemingly stuffed between the pages at random. These papers include received correspondence, newspaper cuttings, various journal and magazine articles, several prints of photographs and sketches, and a few handwritten notes by Curzon. On close inspection, it is clear that someone (presumably Curzon) purposely inserted these papers for safekeeping, in some instances at the precise passages to which they relate. The presence of so many related items, ranging in date from 1892 to 1924, the year before Curzon’s death, strongly suggests that Curzon planned to revise the book. However, it appears that his political career and decline in health ultimately prevented him from doing so.

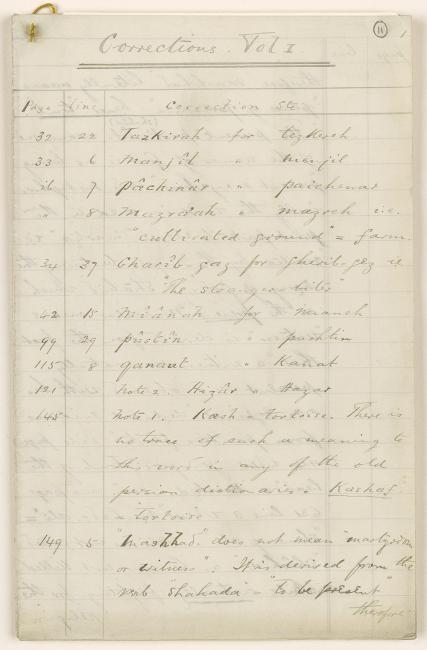

Probably the clearest indication of Curzon’s wish to revise Persia and the Persian Question is a set of handwritten notes, found inside the book’s first volume. Undated, but with the heading ‘Corrections. Vol. I’, they comprise thirty pages of planned revisions, specifying the page, line, and desired correction to the text.

Separated, Reunited, Forever Incomplete

Having so many loose items between the pages of the two volumes poses a challenge: while it is essential for the long-term preservation of the volumes to remove the related items, doing so means losing their links to the corresponding pages in the book. For the QDL, the solution has been to number the pages of the book and the inserted items with the latter still in place, forming a single foliation sequence. Here you will find the inserted items in their original order, between the pages of the two volumes (although some, e.g. certain newspaper cuttings, do not appear online for copyright reasons). For the physical copy, the inserted items have been re-housed in a separate file.

Persia and the Persian Question was an early and significant achievement for Curzon, even if he always considered it incomplete. Digitally preserving the relationships between the book and the re-housed items allows us to study them together and speculate on how Curzon might have revised the book had he lived longer.