Overview

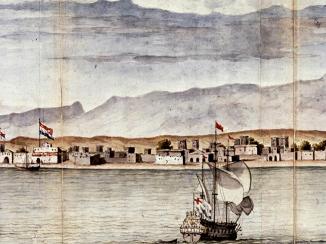

Since its inception at the start of the seventeenth-century, the English East India Company (EIC) had sought a way into Persia, lured by the richness and renown of its principal cities, such as Isfahan and Shiraz. While Britain’s more distinct political and strategic interests in the Gulf grew over time, it was initially a matter of trade with Persia that first invited them to the shores of the Gulf. The trade in textiles would provide them with the key.

Raw Silk for Broadcloth

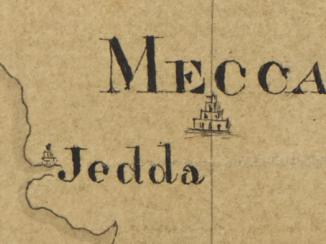

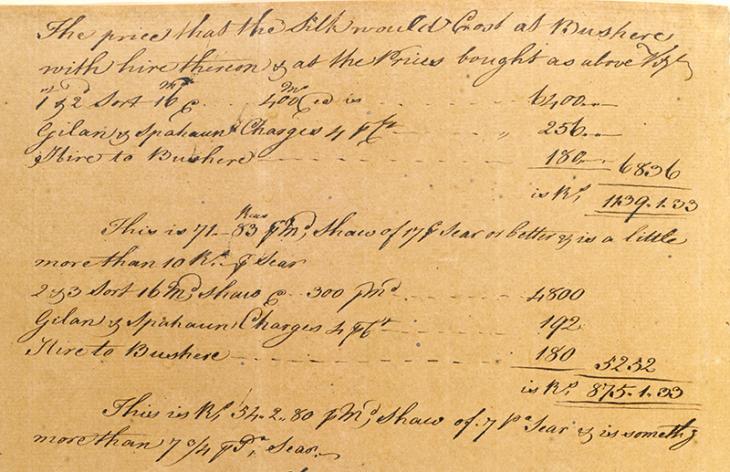

Raw silk, produced in the Caspian Sea region, was a commodity particularly attractive to the EIC. Faced with stiff, well-established competition from other companies and private merchants operating along the land routes into Russia and Anatolia Peninsula that forms most of modern-day Turkey. , however, the EIC had been slow to procure it. It was a shipment of English cloth at Surat – difficult to sell in India’s hot climate – that proved to be the catalyst not only for the EIC’s initial acquisition of silk but also for its entry into the Gulf.

Broadcloth was known to sell well in Persia’s mountainous north where, for half the year, temperatures remained low. It was hoped that a large stock of the densely woven fabric might be exchanged for silk from the province of Gilan. Accordingly, a quantity was taken to Jask on board the James in 1616, thereby laying the commercial foundation of the English presence in the Gulf for the next two hundred years.

To ‘Procure a List of Woollens Proper for the Different Parts of Persia’

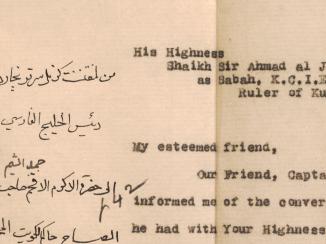

This relationship with Persia, as a market for English cloth and a source of raw silk, was still a primary EIC concern when the Bushire Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. was established in 1763. On 20 April that year, in one of the earliest letters to have been received there, William Andrew Price writes to the new Resident, Benjamin Jervis, setting out the point of the new Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. as being to ‘more particularly introduce the Vend of Woollen Goods into the Kingdom of Persia,’ and impressing the need to ‘procure a list of Woollens proper for the different Parts of Persia together with the annual Consumption’.

The early records from the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. are brimming with references to English woollens, which in turn point to their importance to the EIC. Similarly, the endeavour to maintain a foothold in the silk trade is evident throughout this early correspondence. From Jervis’ report into the state of the trade in 1765, which he believed was promising enough to be entered into ‘with great ease and much advantage’ to a request for the eggs of the silkworm from the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. in October 1830, a consistent interest in trading textiles with Persia is conspicuous.

Demands for Kerman Wool

Kerman wool, also known as Carmenia wool, was the only other export of note, apart from cash, that the EIC obtained from the Gulf. Provided by a species of goat found in the mountains of Kirmān province and useful for the manufacture of felt, the material had first come to the notice of the Dutch and English in the mid seventeenth-century.

Although in decline by the middle of the following century, it remained a preoccupation of the Company’s. Even throughout the turmoil of civil war – which reportedly ‘consumed the greater part of the sheep’ – prior to the establishment of the Qajar dynasty in Persia, repeated requests for Kerman wool were sent to Bushire by the Government in Bombay.

From Trade to Empire

The early letters of the Bushire Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. give a clear indication as to why the EIC were in the Gulf in the first place and provide us with a very particular view of this important inter-continental trade. Interestingly, the same correspondence also reflects changes that were afoot during the period.

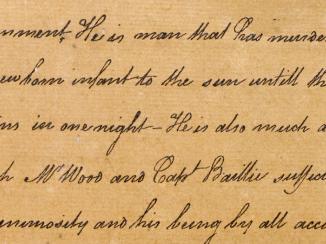

A breakdown in Persian central authority coincided with the rise of Arab tribes, particularly the Bani Utbah and al-Qasimi, in the Gulf. This, coupled with the emerging threat from Russia and France on the Persian frontiers of Britain’s Indian Empire, meant that the Gulf began to take on a new strategic significance for the EIC.

Despite a policy of non-interference, designed to further their commercial ambitions and boost profits, the English slowly began to get drawn into the politics of the region. The trade in textiles had been the foundation for their presence in the Gulf, but the strategic goals of empire – secured by violence and intimidation – which had evolved out of these interests, would soon overtake them.