Overview

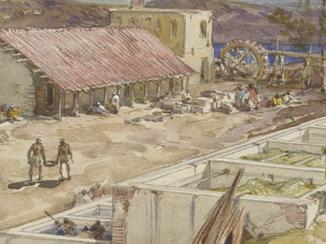

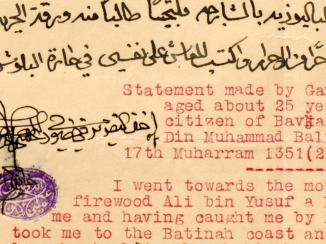

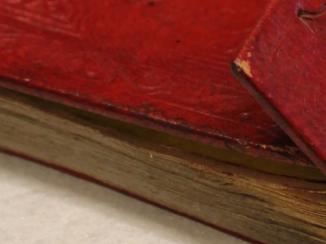

Many files in the British Library’s India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records bear the scars of insect damage. In the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. and Bahrain Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. files, the edges of numerous pages and covers are riddled with small holes, a tell-tale sign of damage by ‘bookworm’ insects: either termites or wood-eating beetles.

Appealing Paper

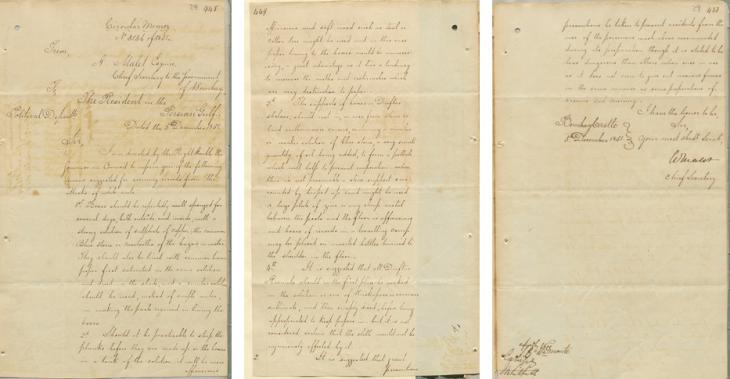

In December 1851, Arthur Malet, Chief Secretary to the Government of Bombay From c. 1668-1858, the East India Company’s administration in the city of Bombay [Mumbai] and western India. From 1858-1947, a subdivision of the British Raj. It was responsible for British relations with the Gulf and Red Sea regions. , sent out a circular memo to officials across British India, containing instructions on how to counter the threat posed by white ants, better known to us as termites, to paper records. Paper and wood are particularly appealing for termites because they contain cellulose, which is a rich source of energy for the insects. In his circular memorandum, Malet advised on how best to discourage termites taking refuge in and eating their way through India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. papers.

Malet’s Conservation Manual

‘First,’ began Malet, ‘boxes should be repeatedly well sponged for several days, both outside and inside, with a strong solution of sulphate of copper […] in water. They should also be lined with common brown paper first saturated in the same solution and dried in the shade, and a similar solution should be used, instead of simple water, in making the paste required in lining the boxes.’

‘Second,’ continued Malet, ‘should it be practicable to steep the planks before they are made up or the boxes in a tank of the solution it will be more efficacious, and soft wood such as deal or cotton tree might be used and in this case paper lining in the boxes would be unnecessary, a great advantage as it has a tendency to increase the moths and cockroaches which are very destructive to paper.’

‘Third, the supports of boxes […] should rest in, or rise from stone or hard earthenware veneers, containing a similar weaker solution of blue stone [copper sulphate], a very small quantity of oil being added, to form a pellicle [or coating] which will help to prevent evaporation – when this is not procurable a stone support surrounded by heaped up sand might be used, a large plate of zinc or any cheap metal between the posts and the floor is efficacious, and boxes of records in a travelling camp may be placed on inverted bottles buried to the shoulder in the floor.’

Hazardous Chemicals

‘Fourth,’ Malet went on, ‘it is suggested that all Duftur Roomals [large squares of cloth] should in the first place be soaked in the solution or one of Ruskapoor [a mercury sulphate solution] or corrosive sublimate, and then simply dried, before being appropriated to keep papers in – but it is not considered certain that the cloth would not be injuriously affected by it.’

The hazardous nature of the measures proposed was not lost on Malet: ‘It is suggested that great precautions be taken to prevent accidents from the use of the poisonous wash above recommended during its preparation, though it is stated to be less dangerous than others when once in use as it does not give out noxious fumes in the same manner as some preparations of arsenic and mercury.’

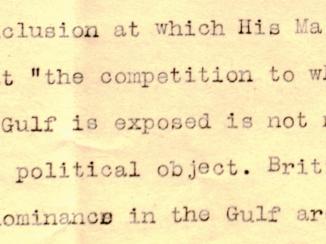

The extent to which Malet’s instructions were followed by Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. staff and, if they were, just how efficacious they proved to be in reducing insect damage to the records is unknown. Modern methods of preservation, such as maintaining cool, low-humidity environments like those in which the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records are now stored at the British Library, help ensure that the risks associated with insect damage are kept to a minimum.