Overview

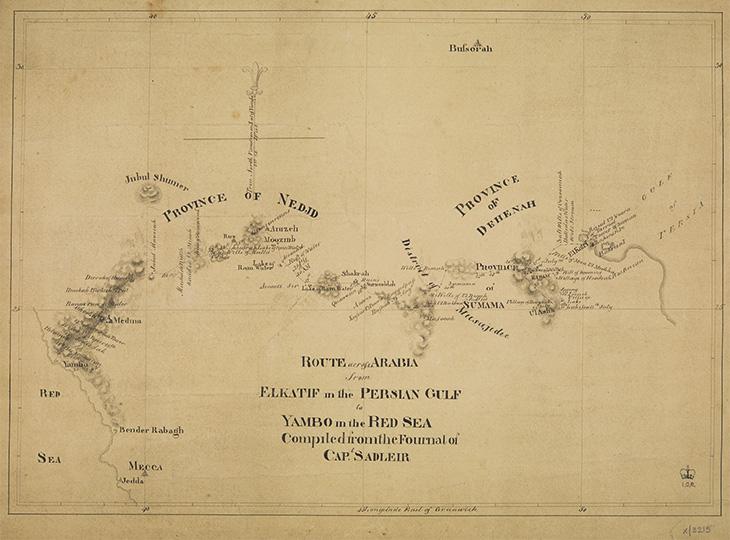

Early British explorers of Arabia made their journeys for different reasons. Fame, fortune, intellectual curiosity or the simple desire for adventure are all factors that compelled these people to risk their lives by travelling there. The first known European to make the hazardous journey across the Arabian Peninsula, George Forster Sadleir, was not motivated by any of these factors. Instead, he travelled through the summer of 1819, from Qatif in the east, to Yanbu in the west, out of a sense of duty to his employers’ designs for the Gulf.

The Reluctant Traveller

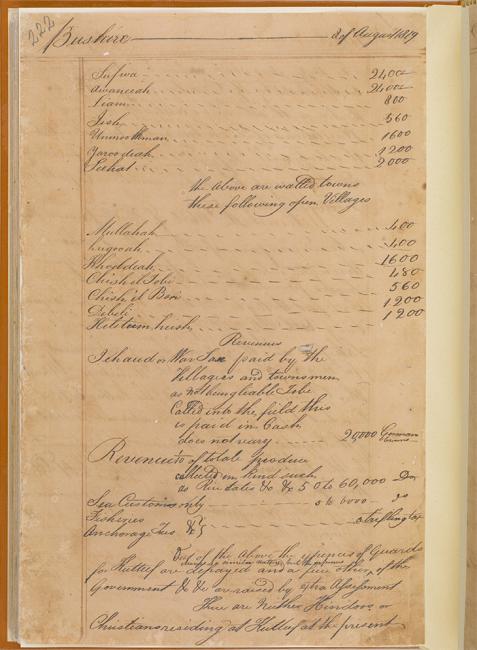

The early correspondence of the East India Company (EIC) Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. at Bushire contains many references to Sadleir’s journey. William Bruce, the Resident at the time, was instructed by his superiors in Bombay to assist wherever possible. A channel of communication with Bushire was evidently open when Sadleir arrived at Ul-Ahsa (Hofuf) as he sent a letter to Bombay via the Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. that included several pages of extracts from his diary.

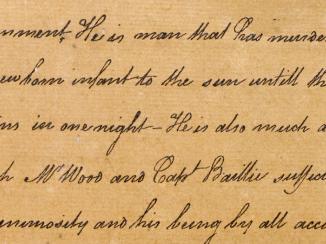

There can be few more reluctant travellers to have ventured into the interior of the Arabian Peninsula. Words like ‘tedious’, ‘uncivilized’, ‘barbarous’, and ‘horrid’ occur regularly in his diary, with little indication of much love for the people or the country he visited. Nevertheless, he scrupulously recorded details of the towns he visits, with lists of populations and notes on trade and agricultural produce. At certain points he describes the people he encountered in the places he passed through and the landscape that surrounded them, much of which was being seen for the first time by Western eyes.

The Dutiful Traveller

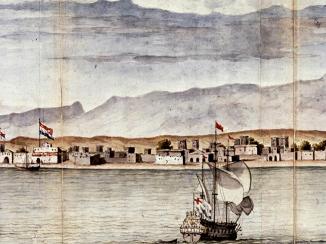

The fact that Sadleir was there in the first place reveals the EIC’s deepening involvement in the politics of the region. In 1818, Ibrahim Pasha An Ottoman title used after the names of certain provincial governors, high-ranking officials and military commanders. had completed his crushing defeat of the first Saudi-Wahhabi state, crossing the breadth of the Peninsula from Egypt and reaching Qatif on the Gulf coast. The EIC sensed an opportunity and with the hope of obtaining his assistance against the ‘pirates’ of Ras al-Khaimah, they resolved to send the Pasha An Ottoman title used after the names of certain provincial governors, high-ranking officials and military commanders. an address of congratulation and a sword of honour. Having hitherto been so unwilling to be drawn into the affairs of Central Arabia, the Company’s decision to send Captain Sadleir on such a mission was significant.

The letters in the Bushire record reveal that Sadleir had given up on the main objective of his mission at an early stage. With Egyptian withdrawal underway, he rightly surmised that if the Pasha An Ottoman title used after the names of certain provincial governors, high-ranking officials and military commanders. was willing to relinquish Qatif, Uqair, and Hofuf, he was unlikely to be interested in Ras al-Khaimah, a place that seemed to have less to offer. Sadleir still had to deliver the sword to Ibrahim, however. A task he felt he must do to avoid the ‘disapprobation of Government’.

An Understated Conclusion

News of Sadleir temporarily ceased following his departure from Hofuf. Indeed, as late as 7 March 1820, Bruce was still waiting for ‘some authentic accounts’ of the Captain’s fate. The difficulty and slowness of communication at that time meant that the Resident wasn’t to know that Sadleir had reached Yanbu on the Red Sea coast almost six months earlier, and had returned to India from there. In pursuit of Ibrahim Pasha An Ottoman title used after the names of certain provincial governors, high-ranking officials and military commanders. , who had withdrawn to Medina, Sadleir had accomplished more than just the mission assigned to him by the EIC; he had completed a crossing of the Arabian Peninsula.

A reluctant and accidental traveller he may have been, but his achievement was extraordinary and was an expression of Britain’s expanding role in the Gulf, beyond the littoral and into the unknown interior.