Overview

Astrology in the service of ambition

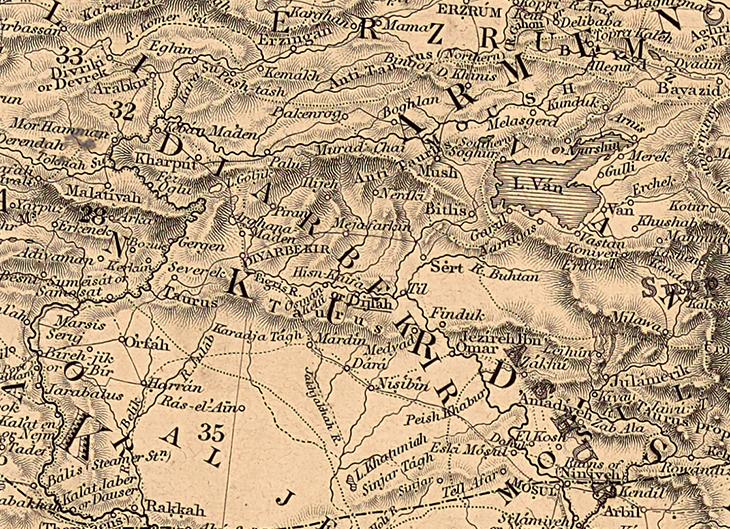

As Abbasid caliphal influence waned in the region of Diyar Bakr (in today’s southern Turkey near the Syrian border), a succession of short-lived Arab, Persian, and Kurdish dynasties fought over this fertile and strategic territory. One such dynasty was the Marwanids, who ruled as semi-independent amirs (regional potentates) between 372-478 AH/983-1085 CE.

Individuals who sought political power at this time played a dangerous game. High office could bring astounding riches and influence, but also carried the ever-present risk of summary imprisonment or execution as a result of conspiracy, incompetence, or whim. In this atmosphere, some turned to the ancient promise of astrology to avoid misfortune or gain advantage, by seeking to understand and profit from the astral influences believed to hold sway over human affairs.

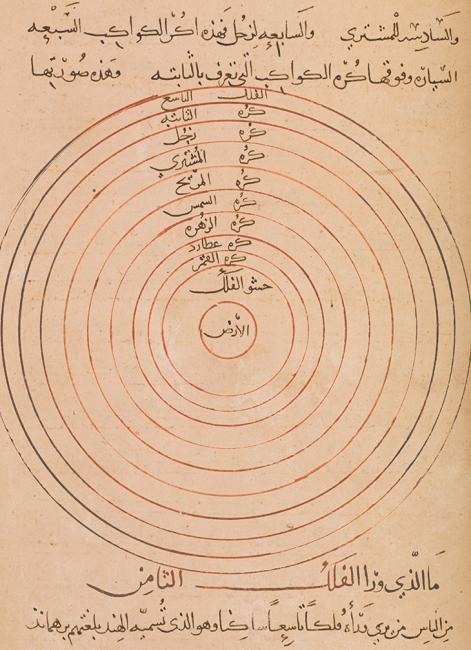

Astrology encompassed numerous sub-disciplines including horoscopes and nativities (Or 8857, ff 1v-2v), judgements (Or 5591, ff 157r-160v, Or 5591, ff 110v-113r), interrogations (Delhi Arabic 1916, Or 12802, Or 9011), historical astrology (Or 7716, ff 1r-117r), and others. The branch concerning ‘elections’ (ikhtiyārāt), especially, was used to establish the optimum moments to conduct (or avoid) certain activities. Rulers consulted astrologers to decide when to wage battle or found cities (notably Baghdad, which was founded on 23 Tammūz 1074 of the Seleucid era/3 Jumādá I 145/30 July 762 upon the advice of a consortium of astrologers). Meanwhile, all classes of society used elections to establish the best timing for marriage, seeking medical treatment, carrying out financial transactions, travelling, and other actions (e.g. Or 5591, ff 3r-18r).

Oriental 5709: The last word on astrological elections

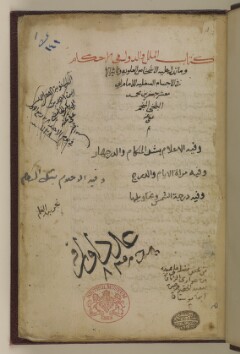

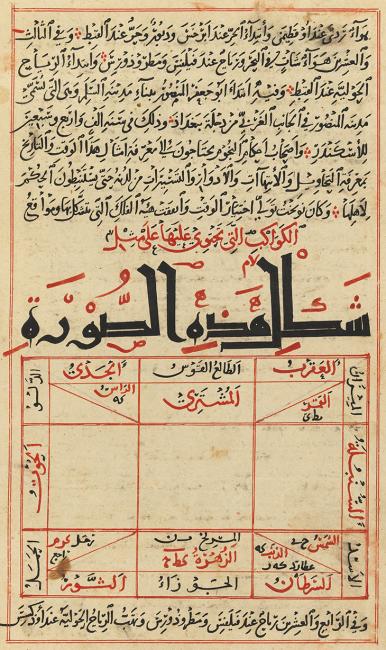

One particular text on astrological elections exemplifies this interest. This 646/1249 copy – probably unique – of Choice Selections of Books of Astrological Elections (Al-Mukhtār min kutub al-ikhtiyārāt al-falakīyah) is an anthology of numerous earlier Muslim, Greek, and Indian authorities on the subject. Further, the story of this text’s composition sheds light on the life and times of one ambitious, and ultimately tragic, family.

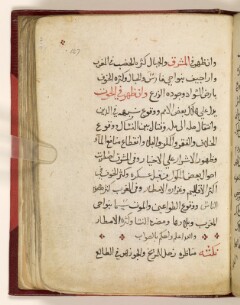

The text was compiled by Abū Naṣr Yaḥyá ibn Jarīr al-Takrītī (fl. 472/1079). He was brother of the personal physician to the fourth Marwanid Amir, Naṣr al-Dawlah Aḥmad ibn Marwān (r. 401–453/1011-61). During Naṣr al-Dawlah’s long reign, the dynasty attained its greatest cultural and economic successes, centred on the flourishing city of Mayyāfāriqīn (today’s Silvan in southern Turkey). Also a physician, al-Takrītī was commissioned to compile the text, as is recorded in its introduction and closing sentence: ‘for the majlis [social and literary gathering] of the most illustrious and cultured lord, Sadīd al-Dawlah Abū al-Ghanāʾim ʿAbd al-Karīm ibn Ibrahīm [ibn al-Anbārī]’ (f. 158r, lines 13-15).

As the historian Ibn al-Azraq al-Fāriqī recounted seventy years later in his History of Mayyāfāriqīn and Āmid, Sadīd al-Dawlah (d. 489/1096) was extremely well connected. His father was vizier (prime minister) to Amir Abū al-Qāsim Naṣr ibn Aḥmad (r. 453-472/1061-79), son and successor of al-Takrītī’s brother’s patron. Additionally, Sadīd al-Dawlah’s brother, Abū Ṭāhir ibn al-Anbārī (d. 489/1096), assumed the vizierate upon their father’s death and continued in power during the early reign of Manṣūr ibn Naṣr (r. 472-478/1079-85), Naṣr ibn Aḥmad’s successor.

The Anbārīs’ fall from power

However, the Anbārī family’s gilded existence did not last. Following a conspiracy, Abū Ṭāhir fell from favour and was imprisoned, only to be released when the Seljuks conquered the Marwanids in 478/1085. The Seljuk campaign was conducted by Fakhr al-Dawlah ibn Jahīr (398-483/1007-1090), working on behalf of the real regional power-holders, the Iṣfahān-based Seljuk Sultan Malik Shāh (r. 465-485/1072-92) and his omnipotent vizier, Niẓām al-Mulk (d. 485/1092). Ibn Jahīr himself had previously served as Marwanid vizier under Naṣr al-Dawlah, before manoeuvring into the post of Abbasid caliphal vizier in Baghdad in 455/1062. He finally, and advantageously, switched his allegiance to the Seljuks in 476/1083.

Ibn Jahīr initially exiled his successor Abū Ṭāhir to Ḥiṣn Kayfā (today’s Hasankeyf), fifty miles away, but soon reconsidered and pursued him again. Ibn Jahīr reportedly planned to seize at least some of the fabulous Marwanid treasury for himself, instead of surrendering it to his Seljuk overlords. According to an earlier testimony, the treasury contained huge pearls, valuable weapons, a Qur’an believed to have been written by Imām ʿAlī himself, and a gigantic jewel known as ‘The Ruby Mountain’ (Jabal Yāqūt) (cf. Amedroz, p. 135). Ibn Jahīr suspected that, as the former vizier, Abū Ṭāhir would know the treasury’s contents and true value, and would inform Malik Shāh if a portion were siphoned off.

Desperate to evade Ibn Jahīr, Abū Tāhir and his associates in Ḥiṣn Kayfā (including historian Ibn al-Azraq's grandfather) feigned his illness and death, even staging an elaborate fake funeral. Put off the scent, Ibn Jahīr retreated, and Abū Ṭāhir laid low until Malik Shāh recalled Ibn Jahīr from Diyar Bakr shortly afterwards.

The family’s fortunes restored… for a while

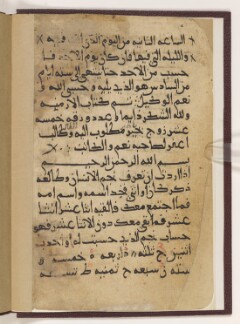

At this point, Sadīd al-Dawlah interceded with Malik Shāh on behalf of his brother Abū Ṭāhir. We can only speculate as to whether he sought advice from the heavens regarding the precise timing, as outlined in al-Takrītī’s manual, before taking this risky step. If he did, ‘Chapter Two (on particular elections) […] Section Twelve: On elections pertaining to the tenth house, regarding the opportune moment for pledging allegiance to a ruler’ would have been of particular interest (Or 5709, ff. 99v-109r). This chapter includes entries on determining when best to meet with sultans and rulers, when to ask them for favours, and when to raise the subject of another person with them.

Abū Ṭāhir was restored to grace, and became Governor of nearby Āmid (today’s Diyarbakır). Following Malik Shāh’s assassination in 485/1092, his brother and rival Seljuk claimant Tutush (d. 488/1095) seized the area of Mayyāfāriqīn and appointed Abū Ṭāhir as Governor there too.

The brothers’ final eclipse

However, after a lifetime of intrigue, Abū Ṭāhir could not trust his newest boss. Fearing he would meet the same fate as another local governor, whom Tutush had beheaded in 487/1094, Abū Ṭāhir fled Mayyāfāriqīn. Nevertheless, he was soon captured, and was executed at Shimshāṭ (Greek Asmosaton [Ἀσμóσατον]) on a tributary of the Euphrates in Jumādá II 489/May-June 1096. Put to death also were his eldest son and his brother, the once-fortunate Sadīd al-Dawlah.

Sadīd al-Dawlah and his brother Abū Ṭāhir lived in a cut-throat milieu, their world overshadowed by a powerful enemy rising in strength. It is hardly surprising that even such an elite figure might wish to have at his fingertips a comprehensive manual on the avoidance of misfortune and the selection of favourable moments. Perhaps, however, his busy life had left him no time to study the extensive astrological compilation that al-Takrītī had assembled at his request.