Overview

The British Library’s Delhi Collection consists of over 3500 predominantly Arabic and Persian volumes, several of which are available on the QDL. The British Library’s Collection Guide describes the acquisition of this collection somewhat neutrally as ‘collected by the Delhi Prize Agents acting on behalf of the British army in the aftermath of the Indian rebellion of 1857.’

India’s Great or First Rebellion was a widespread popular rejection of the East India Company (EIC)’s increasingly heavy-handed military and social policies, and was termed the ‘Mutiny’ in contemporary British accounts. During the rebellion, Delhi was widely sacked by both British and Indian participants. The turning point occurred in September, when the British Army captured the city.

The acquisition of the Delhi Collection immediately after these devastating events begs certain questions. What were the source/s of these manuscripts? Who were the Delhi Prize Agents? By what authority did they offer these volumes for sale?

The Siege of Delhi and Establishment of the Prize Agency

In May 1857, Indian rebels captured the symbolically important Mughal capital of Delhi. It was quickly besieged by members of the EIC army, which had long been under the effective control of the British Government.

To motivate the troops, the EIC military leadership invoked the law of Prize, declaring all the rebel riches of Delhi to be the Army’s property by right of conquest. A group of ‘prize agents’ was elected by the troops to administer the collection and sale of booty (Griffiths, p. 231). These were typically high-ranking and well-connected military officers such as Sir Edward Campbell (1822-82). The Army’s official edict prohibited plundering for personal gain. However numerous records and personal memoirs make it clear that, once the city fell on 14 September, looting by European and Indian soldiers and officers was widespread, tacitly accepted, and retrospectively justified.

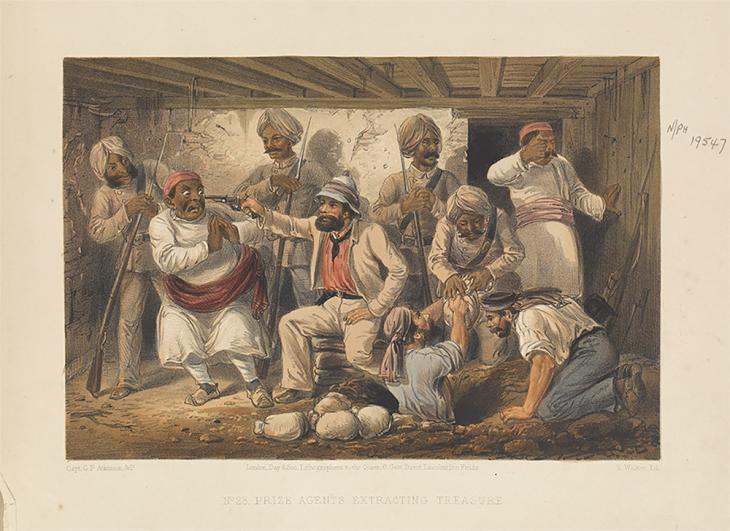

The Prize Agents issued permits to plunder, and booty was seized in a systematic and calculated manner from both rebels and (mostly now abandoned) private households. Most notoriously, floors and walls were excavated inside houses and places of worship to uncover the jewels, cash, and other possessions hurriedly hidden by Delhi’s citizens.

The ‘treasure’ obtained in this manner – at least, that which was surrendered to the Prize Agents – was assembled in Delhi’s abandoned palaces, and publicly auctioned. The proceeds were eventually divided among the troops according to fixed proportions determined by rank.

The Law of Prize: legality and ethics

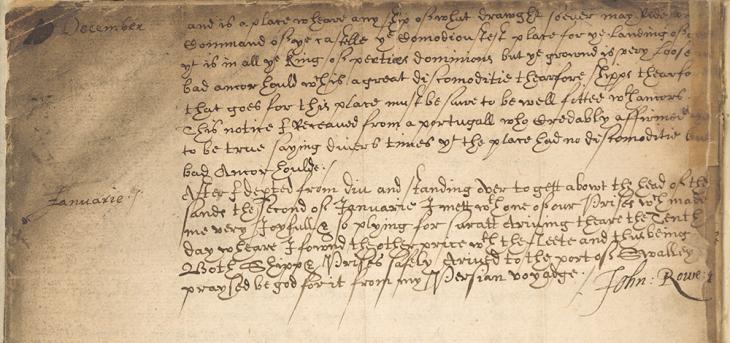

Described by historian William Dalrymple as ‘legalised looting’ (p. 340), prize law originated in European maritime contexts, and was progressively codified by England and other globalising naval powers from the medieval period onward. Prize law took into account traditional practices of pillage whereby common seamen or troops might seize private property found on enemy ships. EIC log-books record the law’s provisions for remunerating troops and disposing of enemy war- and merchant-ships.

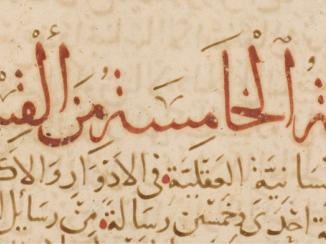

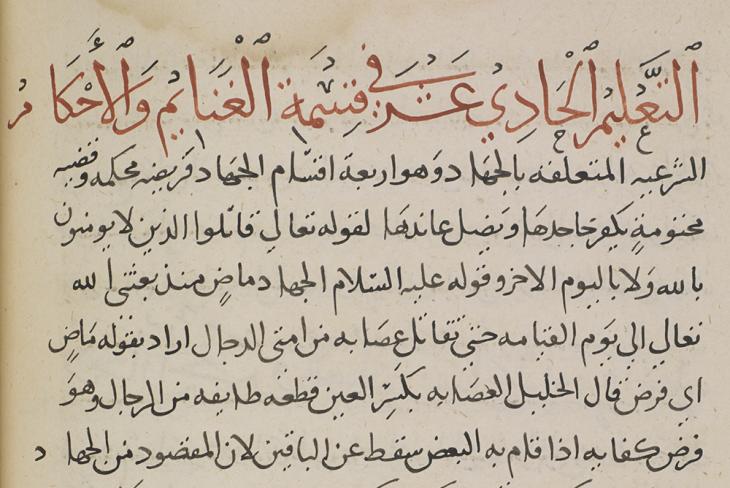

However, the practice was not unique to Europe, as medieval Arabic military treatises also testify. For example, a fourteenth-century manual on military matters and horsemanship by Muḥammad ibn ‘Īsá ibn Ismā‘īl al-Ḥanafī al-Aqṣarā’ī dedicates a chapter to codifying the rules of plunder. In the Indian context, British forces had defeated Tipu Sultan, ruler of the southern kingdom of Mysore, in 1799, seizing approximately 2000 volumes from his library, along with his treasury and weaponry. This victory was also administered according to the law of Prize, and about 600 of these manuscripts are now in the British Library. Tipu’s library had itself been compiled from collections violently taken from southern Indian Muslim courts in the course of his and his father Haydar Ali’s campaigns.

Manuscript Booty: both royal and private

Written heritage, in the form of books and manuscripts, was among the casualties of the violence in 1857. In October, Charles Saunders of the British Intelligence Department in Delhi lamented that ‘a great number of valuable Persian and Arabic books have been most wantonly destroyed by our soldiery, who for the first 10 days after entering the City were almost beyond all control’ (Muir, p. 288).

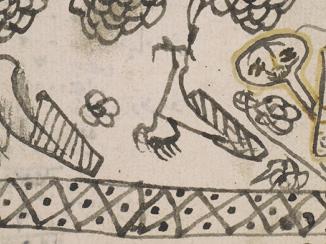

Manuscripts were considered valuable property by many, and were targeted by both private looters and the Prize Agents. Among the Agents’ subordinates and assistants were some who specialised in particular categories of object, including books. When British forces captured the Red Fort (the Mughal palace complex), they impounded what remained of the Royal Library, along with regalia, textiles, and architectural materials. Thus, today the Delhi Collection includes some of the surviving volumes of the once-glorious Mughal library, which was already vastly reduced in 1857 from the 24,000 manuscripts that German traveller Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo recorded in 1638.

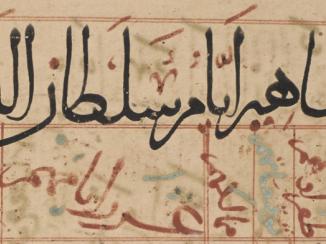

The Prize Agents also targeted private collections belonging or linked to prominent political and literary figures associated with the Mughals, on the basis that their owners had been accused of anti-British rebellion. These too became a major component of the Delhi Collection. The German scholar and Principal at the Calcutta Madrasa, Heinrich Blochmann (1838-78), surveyed the manuscripts in 1869 and identified the ownership or scribal marks of the following: Karim Ullah ibn Lutf Allah (d. 1874), a notable Delhi scholar, author, and scribe; the poet and rebel leader Mufti Sadruddin Khan ‘Azurda’ (d. 1868); and Mufti Fazl-i Haqq Khayrabadi, who had died in exile in 1862. Other libraries seized included those of the court poet Zahir Dihlawi (1835-1911) and of the scholarly descendants, associated with anti-British resistance, of the famous theologian Shah Wali Ullah Dihlawi (1703-62).

While the public Prize auctions continued in Delhi for years, 4700 assembled manuscripts and printed books were purchased in a private sale that was hastily arranged for 1 October 1858. The buyer was the newly-declared Imperial British Government of India, which thereby took possession of the intellectual, symbolic, and literal riches of the subjugated Mughal dominions. Britain had captured the royal and private libraries of Delhi and sold them back to themselves in a procedure that scholar Patrick J. D’Silva terms ‘manuscript-laundering’ (p. 57).

According to Major Lees, who was tasked with assessing and cataloguing the manuscripts, they were already in ‘lamentable condition’, and despite conservation and rebinding they suffered further deterioration (IOR/P/434/1, p. 749). Sent to Calcutta in ‘beer chests’ in 1859, they were then poorly stored, exposed to insect damage, graffitied by British soldiers, and in 1866 damaged by rains and disordered during the hurried rescue effort (IOR/P/434/1, p. 752).

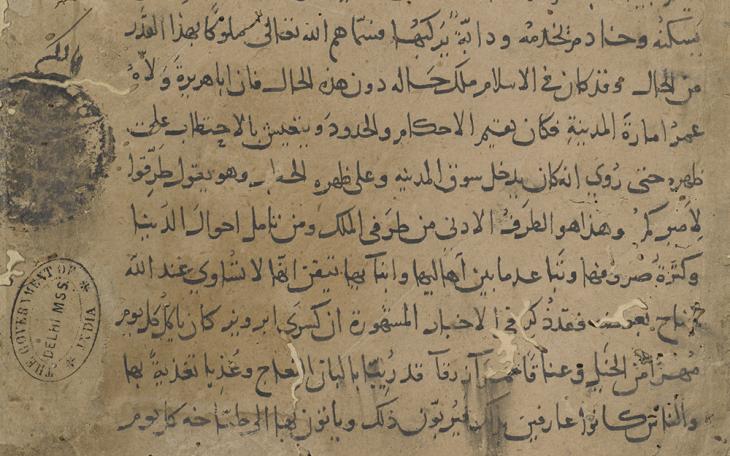

The printed books – regarded as uninteresting – were sold off, along with 1120 manuscripts which the Government deemed less valuable. Finally, in 1876, after the manuscripts had been rejected by the Imperial Museum in Calcutta, they were stamped with a Government seal and sent to London, where they were deposited in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Library, and ultimately transferred to the British Library.

The Delhi Collection Today

After 160 years of intermittent attention and outright neglect, the conservation needs of the Collection are being addressed. Scholars and curators are drawing attention to its rich literary, intellectual, and historical significance, as well as its problematic provenance. In addition to the Arabic manuscripts on the QDL, the British Library has also made available an online index and concordance to unpublished catalogues of Arabic and Persian manuscripts from the Delhi Collection. With ever improving online accessibility, these manuscripts and the records testifying to their eventful biographies can increasingly speak for themselves.