Overview

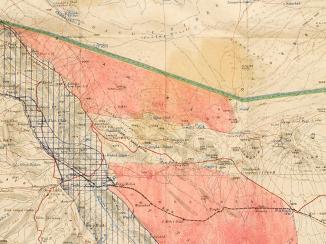

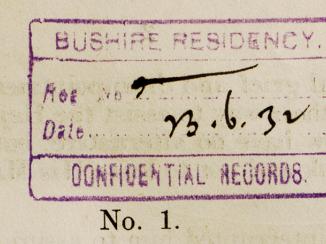

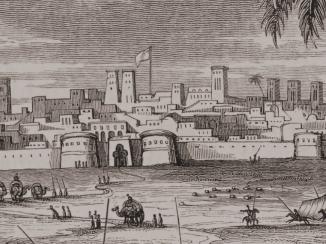

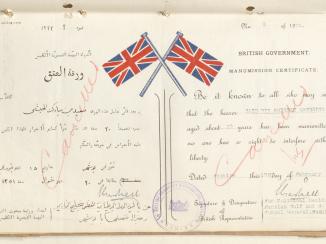

Files in the India Office The department of the British Government to which the Government of India reported between 1858 and 1947. The successor to the Court of Directors. Records, compiled between 1920 and 1951 by Britain’s Political Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. at Bushire (Bushehr) and its Political Agencies in the Gulf (Bahrain, Kuwait, Sharjah, Muscat), contain hundreds of slave manumission statements. The statements exist as a result of Britain’s policy in the Gulf of freeing slaves (albeit subject to certain conditions) who applied for manumission at British Political Agencies. A growing number of these manumission statements are now available to the public on the Qatar Digital Library.

Application Requirements

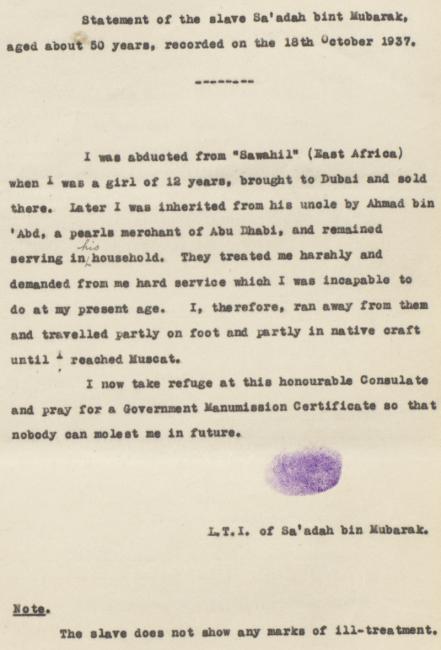

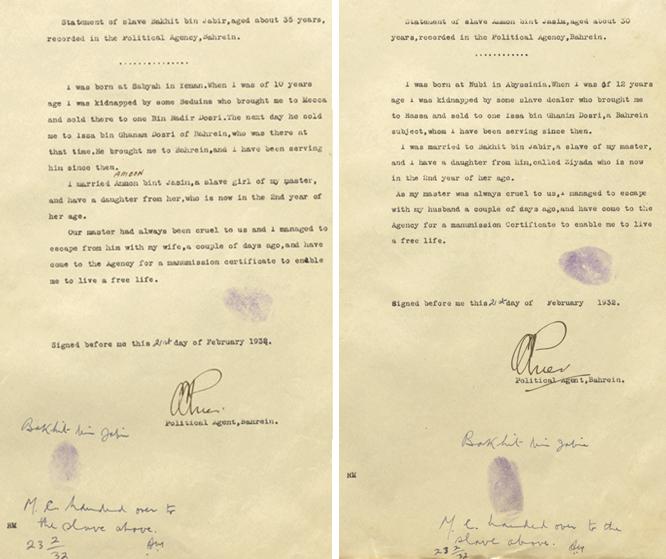

Slaves who requested manumission were interviewed by staff at the relevant Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. . In almost all cases, the interview adhered to a rigid format, intended to extract the following key pieces of information to establish the grounds for manumission:

- The date of the slave’s application for manumission, along with any recognisable signs of mistreatment, as observed by the Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. staff;

- The slave’s name, approximate age, and gender;

- The slave’s origins, if known, and how they had come to be enslaved;

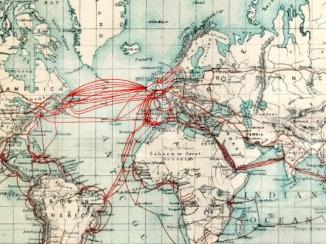

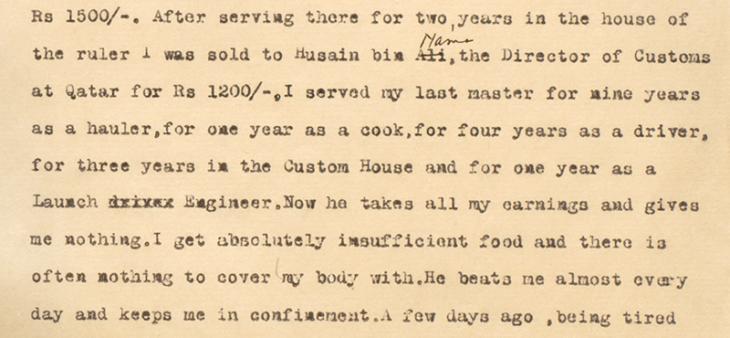

- Details of their path from enslavement to their present situation, including previous owners, routes along which they had been traded, and prices for which they had been sold;

- The roles they had undertaken as slaves;

- Their reasons for absconding from their masters.

Many statements bear an imprint of the slave’s left thumb in lieu of a formal signature.

The Lives and Work of Enslaved People

Despite the strict structure of the questioning and the use of stock phrases, as well as the fact that the manumission statements only survive as they were recorded and transmitted by Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. staff, they nevertheless offer a rare glimpse into the lives of the Gulf’s enslaved population – and in some instances their lives before they were enslaved. For example, a young man named Ganhaj was taken from his home in Baluchistan when he was about ten years old:

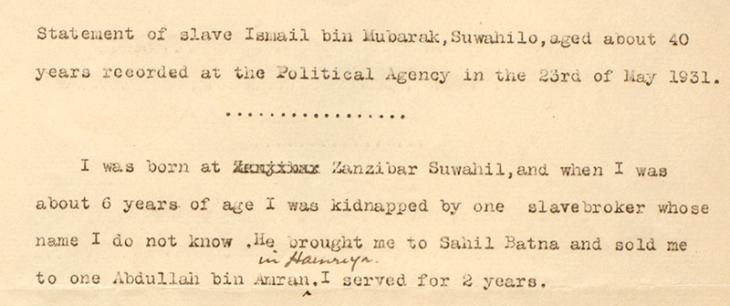

Similarly, Isma’il bin Mubarak was kidnapped at the age of six in Zanzibar, East Africa, in the late nineteenth century, and remained a slave for over thirty years:

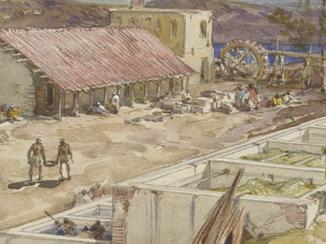

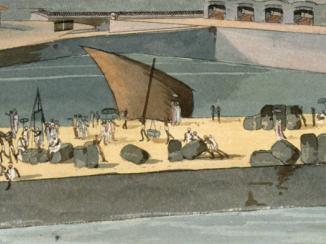

The manumission statements also offer insights into the working lives of enslaved people in the Gulf region. Enslaved men seeking manumission outnumbered women by a ratio of approximately three to one. Most of the men worked as indentured labourers in the pearling industry. After pearling, domestic servitude was the next most prominent area of work. Here, more women than men sought manumission. Of the men who described themselves as domestic servants, two thirds indicated that domestic service was not their main duty; it is likely that they worked in the pearling industry, and were only assigned domestic work by their owners outside of the pearling season, which typically ran from May to October. Other chores undertaken by enslaved people included herding, working on date plantations, water carrying, and collecting firewood. The majority of these tasks were carried out by male labourers, and most were probably fulfilled outside of the pearling season. The manumission records also include a small number of women describing themselves as concubines.

Reasons to Seek Manumission

Another aspect of life that the manumission statements shed light on is the relations between enslaved people and those who claimed ownership of them. Not surprisingly, the statements tend to describe relations between slave and ‘master’ at the point where relations had either changed dramatically or broken down completely, making life for the slave unbearable, uncertain, or both. Violence, abuse, imprisonment, and ill-treatment dominate the reasons given by slaves who took flight from their owners. Indentured pearl divers often claimed they were being given insufficient food and clothing, most likely because their nakhudas struggled to afford the cost of maintaining slaves as the pearling industry went into decline.

Those seeking manumission also frequently expressed a fear of being re-sold by their current owner, the implication being that a tolerable life might soon be supplanted by one much worse. Older slaves, many of whom had spent most of their adult lives as enslaved persons, often sought manumission because they were too old or no longer able to work. Others might already have been freed by their owner (manumission is encouraged in the Qur’an), or their owner might have died, but they still needed an official certificate to prove their manumitted status.

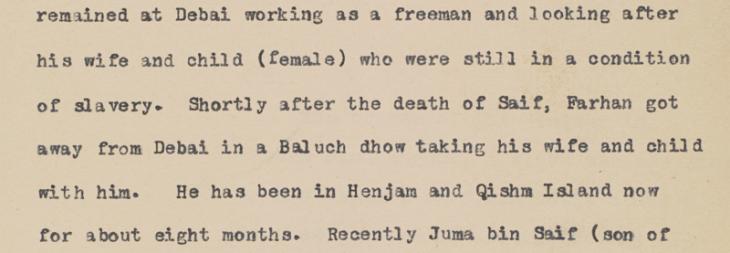

Beyond this, the manumission statements go some way to documenting the social relations of the Gulf region’s enslaved peoples. They give us an idea of their family lives and the struggles encountered by many in keeping their families together. Many of those seeking manumission spoke of mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, and sons and daughters. In a large proportion of these cases the underlying reason behind their application was a desire to be reunited with family members – or the fear of being separated from them.

Different Perspectives

There is a considerable amount of information missing from the manumission statements. There is scant evidence, for example, of the ways in which enslaved people held on to the cultural traditions they brought with them from their places of origin, such as the various forms of ritual, music, and dance that enslaved African people brought to the Gulf. Nevertheless, whatever the shortcomings of the manumission statements as documents on the lives of the region’s enslaved population, they are a welcome alternative to the voices of colonial administrators that dominate the records of Britain’s agencies in the Gulf.

Manumission statements on the Qatar Digital Library

The majority of manumission statements made at Britain’s offices in the Gulf between 1920 and 1950 are contained within several archival series, as follows:

- In the Political Residency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, established in the provinces and regions considered part of, or under the influence of, British India. files: File 5: Slave Trade (IOR/R/15/1/199-234)

- In the Bahrain Political Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. files: File 11: Slave Trade (IOR/R/15/2/1365-1367)

- Part of the Bahrain Agency’s Vernacular Office Files (IOR/R/15/2/1824-1857)