Overview

The earth’s magnetic field has been a source of fascination and interest to mathematicians, geographers, and scientists for thousands of years, with the first measurements of the field having been taken in the fourth century BCE. The modern approach to understanding the magnetic field began in the 1600s with the work of William Gilbert, who published de Magnete based on his own experiments with a magnetic model of the earth.

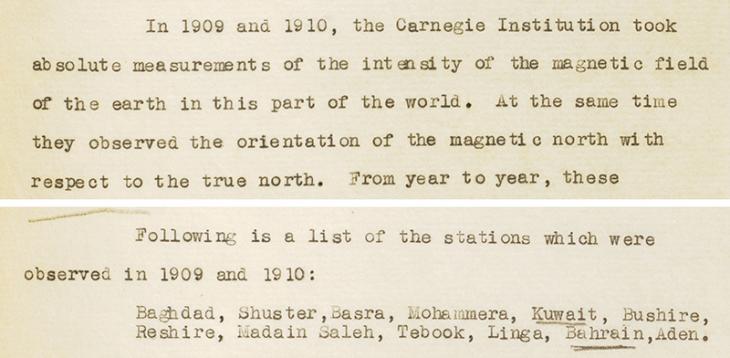

The first modern measurements of the field were taken in 1835 by Carl Friedrich Gauss; since then regular measurements have been taken as scientists have tried to understand the strength of the field, its rate of decay, the orientation of magnetic north, and how and why it varies.

The Carnegie Institution’s Work

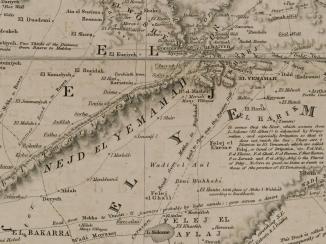

By the 1930s the scientific community understood that the magnetic field surrounding the earth varied and moved over time, but they wanted to understand why, as well as how frequently, it changed. In order to acquire the scientific data required for such an understanding, regular readings were needed from sites across the globe. The Department of Terrestrial Magnetism at the Carnegie Institution in Washington DC took the lead in trying to encourage geophysicists who were travelling the world to take terrestrial magnetic observations and report their findings back to the Institution.

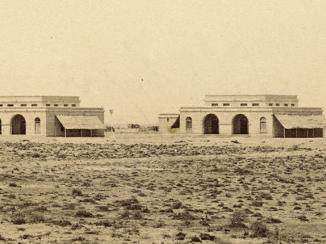

One such geophysicist was Paul Heath Boots, who sought to undertake seismic surveys in Kuwait at possible oil field sites. Boots was aware that it had been over twenty years since the last readings had been taken at various sites in the Gulf – the last comprehensive survey had been completed in 1909–10 – and he was keen to use his visit to Kuwait as an opportunity to acquire new readings for the Carnegie Institution, not only from Kuwait but from Bahrain and Persia too.

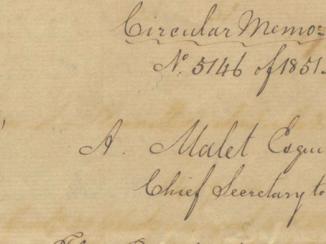

Boots’ desire to take readings in Bahrain had to be approved by the Shaikh of Bahrain and the Bahrain Petroleum Company. Both had to be convinced that his intentions in travelling to Bahrain were for purely scientific reasons and not an attempt to acquire information on oil fields there for commercial purposes. Correspondence from Boots to the Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Bahrain contains not only detailed information about the equipment he would be using to take the required measurements, but also the exact details regarding the site, located on the property of the American Mission in Bahrain, where the last survey readings were taken.

Looking to the Future

It was hoped that the new readings would enable the experts studying the earth’s magnetic field to continue developing their understanding of the ways in which it had varied since observations had last been completed over twenty-five years before, as well as of the rate at which the field’s strength had decayed.

Since 1991 there has been an ‘International Real-time Magnetic Observatory Network’ of over one hundred interlinked geomagnetic observatories working to record the earth’s magnetic field. While the network of satellites orbiting the earth is a far more reliable means of measuring and recording the earth’s magnetic field, international co-operation still plays a valuable role in such scientific observations.