Overview

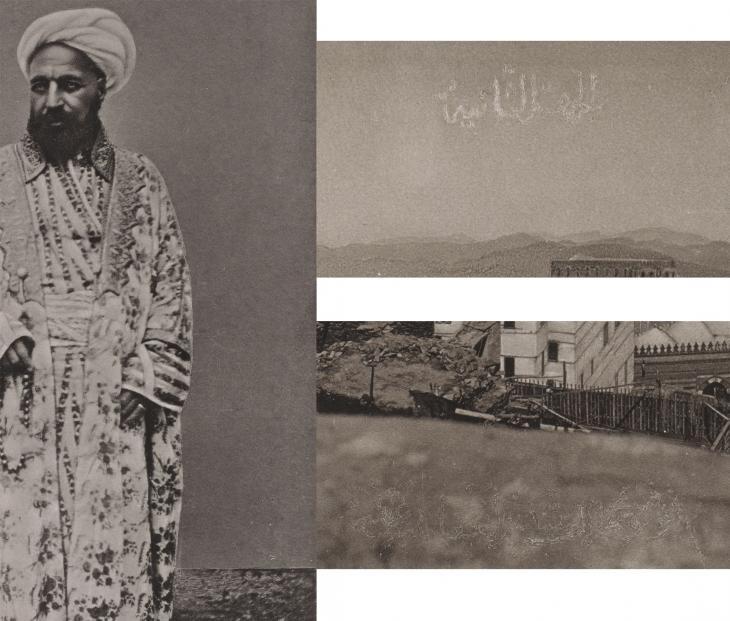

Although once described by his onetime working partner, the Dutch Orientalist Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje, as ‘neither scientific nor systematic’ in his approach to his subjects, al-Sayyid ‘Abd al-Ghaffār is now recognised as the first Meccan photographer.

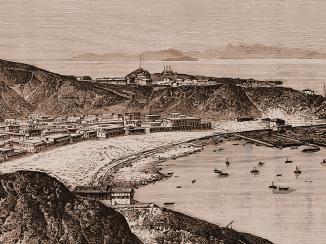

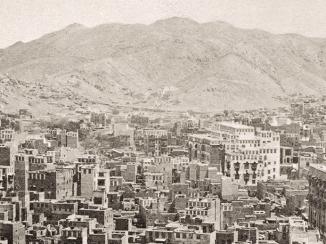

During the period 1886-89, ‘Abd al-Ghaffār took more than two hundred and fifty photographs of Islam’s holiest city and its residents as well as the first photographs of pilgrims participating in the Hajj.

What remains of his oeuvre consists of the material he sent to Snouck Hurgronje in Holland, some of which was later published alongside Snouck Hurgronje’s own photography in the publications, Bilder-Atlas zu Mekka (1888) and Bilder aus Mekka (1889). Together the publications offer an insight as much into the prevailing ideologies of the time in Western European scholarly circles, such as those Snouck Hurgronje aimed to reach, as into the private lives and practices of locals and pilgrims in 1880s Hejaz.

Morsels of Information from the Archive

The majority of what is known of ‘Abd al-Ghaffār can be gleaned from what is recorded, sometimes in passing, within Snouck Hurgronje’s diaries and correspondence regarding his experience in Mecca, 1884-85. When they met ‘Abd al-Ghaffār was already a practising photographer: he enthusiastically offered Hurongrje the use of his ‘inadequate’ studio.

Snouck Hurgronje also records that ‘Abd al-Ghaffār was a technically accomplished man: apart from his photographic work, he practised as a dentist, watchmaker, gunsmith and smelter of gold and silver. He was also clearly enthusiastic about the ‘new’ photographic techniques that Snouck Hurgronje could pass on, such as the dry-plate method.

Working on Commission

After Snouck Hurgronje was forced to leave the Arabian Peninsula, ‘Abd al-Ghaffār made use of some of the albumen Method of printing photographs using an emulsion of salt and egg white (albumen). paper and one hundred and forty-four glass plates that Snouck Hurgronje left with him. It is clear that ‘Abd al-Ghaffār’s chosen subject matter in the years after Snouck Hurgronje’s departure was dictated in part by his continued correspondence with the Dutchman. Snouck Hurgronje sought a full spectrum of Meccan archetypes for his continued ethnographic work – women, slaves, members of the lower classes and other anthropologically-oriented subjects – only some of which ‘Abd al-Ghaffār was able or willing to supply.

![‘Mekkanerin im Brautanzug’ [Meccan Woman in Bridal Costume] by al-Sayyid ʻAbd al-Ghaffār, 1887–88. 1781.b.6/59, p.27r-c](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/1781.b.6_0101_web_0.jpg?itok=zEa5HYjc)

Nevertheless, ‘Abd al-Ghaffār managed to send more than two hundred and fifty prints to Snouck Hurgronje in fifteen consignments over the period 1886–89, many of which Snouck Hurgronje subsequently published in his volumes of images.

Secular and Scholarly vs. Commercial and Religious Photography

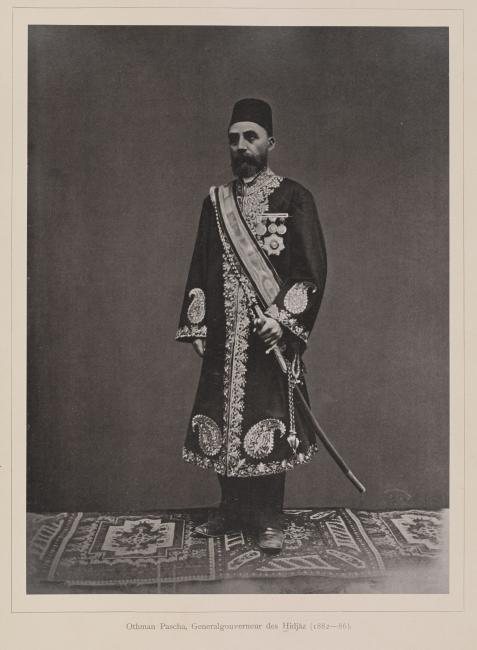

For his studio portraits, ‘Abd al-Ghaffār used decorative backgrounds and props, similar to other formal Ottoman portraits, such as the roughly contemporaneous work that can be found in the Sultan Abdulhamid II albums at the British Library and Library of Congress. However, they are no longer evident in the images published in 1888 and 1889 because Snouck Hurgronje removed them before publication, using paper stencils, during the printing process.

Such props contradicted Snouck Hurgronje’s aims: to decontextualize the subjects of his photographs in order to render them worthy of ‘scientific’ study, as ‘types’. He was careful, too, in removing ‘Abd al-Ghaffār’s signature as well as any other Arabic script written into the negative, which he felt would undermine the secular particularity of his desired subjects.

The Two ‘Abd al-Ghaffārs

When Snouck Hurgronje arrived in Mecca in February 1885, he must have been surprised to encounter a fellow photographer with a functional studio. Perhaps all the more so because, in a most unlikely coincidence, that man shared the name he had adopted upon his own conversion to Islam just weeks before, ‘Abd al-Ghaffār.

Once Snouck Hurgronje left the Arabian Peninsula, it is clear that he sought to manipulate ‘Abd al-Ghaffār from abroad, convincing him that he could earn a good living from portrait photography and, if he would agree to take photographic commissions, Snouck Hurgronje would help him to sell even more prints in Europe.

Subsumed

Snouck Hurgronje felt that by meting out his stock of glass plates sparingly to ‘Abd al-Ghaffār he could control what and whom the doctor could photograph, explaining to van der Chijs in 1886 that ‘[t]his is an excellent supplemental method of coercion’. Similarly, he sent ophthalmic equipment to the doctor, but only irregularly, later writing of the equipment: ‘[t]here’s no hurry […] and a little delay may engender photographs of people and things’.

What remains of ‘Abd al-Ghaffār’s unpublished photographic work, or at least that which can be definitively attributed to him, is held at the University of Leiden’s Library within the Snouck Hurgronje archive – once again subsumed under the Dutchman’s name. In the 1889 publication that featured the first major series of photographs of pilgrims undertaking the Hajj, he was mentioned by Snouck Hurgronje only as ‘the Meccan doctor, that […] I taught’. Today his photographs speak for themselves, providing an alternative view to those more common Orientalist scenes from the period.