Overview

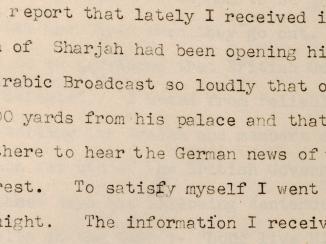

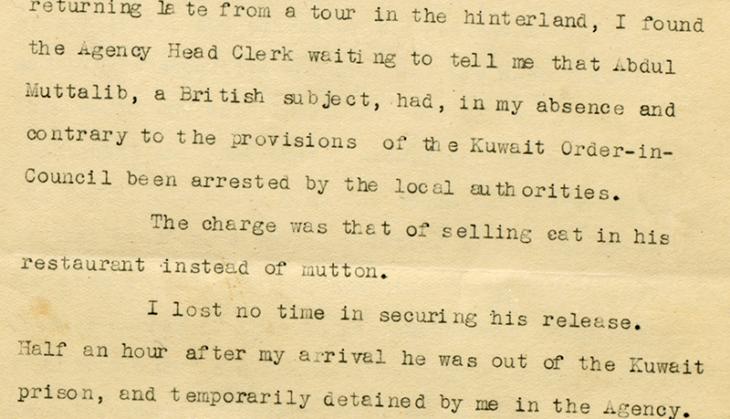

On 11 January 1937, the British Political Agent A mid-ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Agency. in Kuwait, Gerald Simpson DeGaury, was informed that a Pathan [Pashtun] restaurant owner named Abdul Muttalib bin Mahin had been arrested by the local authorities on charges of ‘selling cat in his restaurant instead of mutton’.

Selling Cat Meat instead of Mutton?

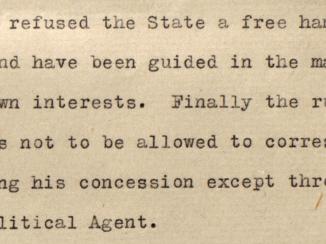

As he was a British subject, Muttalib’s arrest was contrary to the provisions of the Kuwait Order-in-Council (the agreement between the British government and Kuwait’s rulers that governed the relationship between the two). The details of this incident are outlined in a letter DeGaury wrote to his superior, the British Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , Trenchard Craven Fowle, on 18 March 1937.

According to the letter, DeGaury secured Muttalib’s release from prison and detained him in the Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. instead.

‘A Herd of Eight Fat Cats’

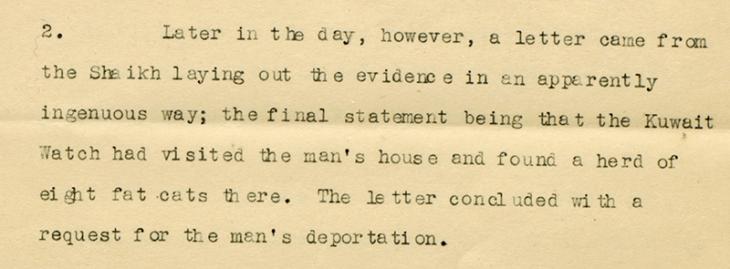

The next day a letter from Shaikh Ahmad Al Jabir Al Sabah arrived at the Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. , presenting the ‘evidence’ against Muttalib. According to the letter, the Kuwait Town Watch had visited Muttalib’s house and ‘found a herd of eight fat cats there’. The letter requested that DeGaury approve Muttalib’s deportation from Kuwait. In the words of DeGaury, ‘His Excellency’ had convicted Muttalib and ‘I was to be merely his executive official for the deportation’.

Shaikh Ahmad’s Lieutenant called at the Agency An office of the East India Company and, later, of the British Raj, headed by an agent. the next day, and was informed by DeGaury that he would try Muttalib the following day. In his letter to Fowle, DeGaury states that as he had previously seen an unusual number of cats in the Lieutenant’s own home, he ‘sharply’ asked him how many he himself kept, to which the Lieutenant fearfully responded that his household had ‘about fourteen, including those in the harem (the area of a traditional Islamic household solely for women)’.

Evidence: A Dead Cat’s Hair

The next day, DeGaury was informed that Shaikh Ahmad had gone away on a hunting trip and it was not possible to call the witnesses to trial without the Shaikh’s permission. DeGaury held the trial regardless and dismissed the case against Muttalib due to a lack of evidence. DeGaury also mentioned to Fowle that the American Mission (The Arabian Mission of the Reformed Church in America) had become involved in the case against Muttalib ‘with their habitual elan’.

When Dr. Charles Stanley Mylrea from the Mission’s hospital analysed a hair found by the Mayor of Kuwait in Muttalib’s restaurant, he had certified it to be the same as that on a dead cat found in a dustbin in the neighbourhood. However, much to the chagrin of the Mission, DeGaury decided that Mylrea’s assessment carried no weight as evidence.

Playing on the Shaikh’s Weakness

The town had split into pro and anti Muttalib factions and in order to publicly show his support for Muttalib he visited his restaurant and rebuked the Mayor, who had initially brought the case against the restaurateur. DeGaury’s actions combined with pressure from the religious establishment in Kuwait – who also supported Muttalib, ‘owing to his past charity’ – soon led the local authorities to lose interest in the case.

DeGaury believed that the Mayor had initiated the case in order to try and gain control of Muttalib’s restaurant and had been assisted by the Lieutenant, said by DeGaury to be an ‘ambitious, jealous man who plays on the Shaikh’s weakness’. DeGaury explained that the Mayor made the error of attacking a British subject thinking that foreigners would be ‘easier game’ than Kuwaitis and since Shaikh Ahmad had ‘concealed the provisions of the Kuwait Order-in-Council from most of his subjects’.

Diplomatic Humour

After receiving DeGaury’s letter, Fowle reported the details of the case to the British Government in India on 5 May 1937. In his letter, Fowle joked that using the ‘capital’ of fourteen cats, the Lieutenant and the Mayor ‘could doubtless have started a flourishing business in the restaurant line’.

Although the charges against him were dropped, believing that his business would suffer as a result of the accusations, Muttalib wound up his affairs and left Kuwait. Fowle sardonically remarked that it was not known whether he left ‘with or without his eight cats’. Thus ended what was known as the ‘Kuwait Cat’s Meat Crisis’, and in DeGaury’s words ‘at one time threatened to be rather serious’.

DeGaury may have sympathized with Muttalib’s plight on a personal level, but the underlying motivation for his decisive action clearly has a wider context.

As DeGaury observed, many Kuwaiti subjects were ignorant of the extent to which the Kuwait Order-in-Council infringed on the country’s sovereignty and the protection that it supplied to British subjects. Muttalib’s almost immediate release from prison and the dismissal of the case against him the next day sent a strong message that British subjects, even those accused of a crime, were under protection and could not be arrested or prosecuted by the local authorities. The crisis therefore served to underline Britain’s dominant position in Kuwait.