Overview

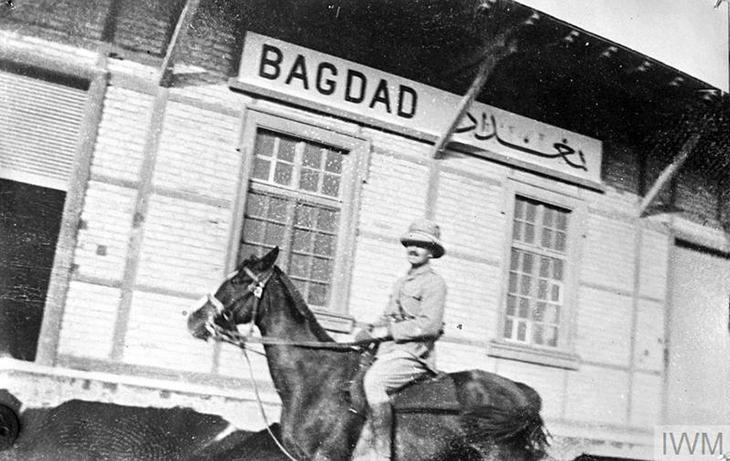

The construction of railways was an essential part of the British Indian Army’s campaign against the Ottoman Empire in Mesopotamia during the First World War. Beginning with the occupation of Basra in November 1914, the Mesopotamia Expeditionary Force (also known as ‘Force D’) went on to seize the key cities of Baghdad and Mosul, and establish a rudimentary colonial administration across the region of what now constitutes Iraq. The success of this campaign largely depended on the construction of a network of railways linking the primary British base at Basra to tens of thousands of soldiers stationed across Mesopotamia. Maintaining a reliable supply of food, weaponry, and reinforcements gave British forces a decisive advantage over the increasingly exhausted Ottoman armies attempting to stop their advance.

But railways did not solely serve military purposes. The War Diaries of Force D reveal that British colonial officials were considering Britain’s post-war imperial objectives alongside the requirements of the army, and that they directed railway construction in Mesopotamia accordingly. British planners intended to build a transport network that could support the entrenchment and administrative requirements of a colonial regime once the conflict had ended.

The Many Uses of Rail

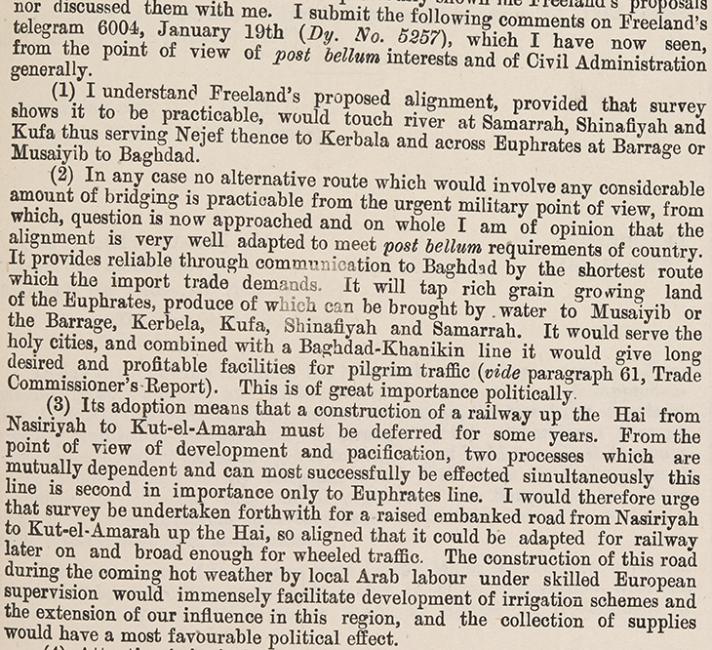

Railways were conceived as both revenue generators and infrastructure for a future British-controlled state in Iraq. In a telegram from February 1918, the British Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. in the Persian Gulf The historical term used to describe the body of water between the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. , Sir Percy Cox, comments that a proposed rail route from Basra to Baghdad would ‘meet post bellum requirements’ for better communications with Baghdad, and improve transportation for Mesopotamian pilgrims. He further argues that immediate military needs could be coordinated with ‘development and pacification’ in the interests of long-term British hegemony in Mesopotamia.

Cox consistently advocated for railway routes that could both serve post-war imperial goals and provide military support. In a telegram from November 1918, for example, he argues that the construction of a line from Nasiriyah to Hillah was ‘of considerable importance from political and commercial point of view’, whereas a line between Baghdad and Kut was ‘a military necessity only’ and should therefore be delayed (IOR/L/MIL/17/5/3312, f. 36r). While it is not clearly stated, it seems likely that Cox’s approach to infrastructure in Mesopotamia was shaped with an eye to the needs of post-war British control. If British officials were hoping that economic prosperity would make an ongoing British presence more palatable to Mesopotamia’s inhabitants, then efficient and well-planned railways would be vital to achieving that prosperity.

Such an approach to infrastructure construction was a long-established element of British imperialism. The railway networks of the British Raj were designed with both economic profitability and military utility in mind, connecting ports to inland sites of resource extraction and ensuring a steady supply of reinforcements and weaponry for the various garrisons across British India. Cox and his fellow imperial administrators intended to replicate this successful system of colonial control in Mesopotamia.

![Photograph of a temporary railway bridge in Ceylon [Sri Lanka], June 1893. Experience of colonial railway construction proved crucial to British success in Mesopotamia. Photo 1178.(1). BL Images online](https://www.qdl.qa/sites/default/files/styles/standard_content_image/public/photo1178-1_web.jpg?itok=Y2FP-qDB)

Rivalries via Railway: The Struggle for the Mosul Vilayet

British railway construction in Mesopotamia was also informed by inter-imperial rivalries. This was clearly demonstrated during the controversy regarding control over the Mosul Vilayet, an Ottoman administrative region centred on the city of Mosul. When the Armistice of Mudros was signed on 30 October 1918, this area was still controlled by the Ottoman army. The terms of the Armistice stated that both the British and Ottoman militaries would remain in the positions they held when it was signed. However, in violation of the armistice and in a grab Shallow vessel with a projecting bow. for more territory, British forces continued their advance, occupying Mosul city and establishing their own military claim to the Vilayet on 14 November. The issue was further complicated by the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, in which the French and British governments had determined that Mosul would be a part of France’s post-war colonial sphere of influence. There were therefore competing British, French, and Turkish nationalist claims for control of the Vilayet.

This uncertainty is reflected in discussions documented about linking Mosul to the rest of British-occupied Iraq by rail. As the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. notes in a telegram from the day British troops occupied Mosul, such a connection was ‘of primary importance, if we are to include this Vilaiyet [sic] within the boundaries of the Iraq state’ (IOR/L/MIL/17/5/3312, f. 36r). Building rail links to Mosul would make the establishment of British control there easier, and would symbolize the British Government’s intention to include the area in a future Iraqi state. If, on the other hand, it was decided that Mosul would ‘fall within the French sphere’, the Political Resident A senior ranking political representative (equivalent to a Consul General) from the diplomatic corps of the Government of India or one of its subordinate provincial governments, in charge of a Political Residency. questioned whether railway materiel ‘so urgently required elsewhere’ should be used for this purpose (IOR/L/MIL/17/5/3312, ff. 36r-37r). The lack of rail connections undermined the effectiveness of the British garrison in Mosul, prompting the commander of British forces in Mesopotamia, Sir William Marshall, to request in February 1919 that the railway be extended to the contested territory. On this occasion, however, military needs were subordinated to imperial diplomacy, and the War Office refused to sanction the extension, simply citing ‘political reasons’ – most likely to avoid antagonizing France (IOR/L/MIL/17/5/3318, f. 49r).

Occupation by Rail

Railways remained critical as British activities in Mesopotamia transitioned from wartime campaigning to colonial occupation. When the Kurdish leader Mahmud Barzanji rose in rebellion against the occupation in June 1919, transport infrastructure proved essential to the British military response. General Marshall stated at the time that he had sufficient forces to defeat the Kurdish uprising, but that the main difficulty was transport. In his communications, he argues that the railway line from Qizil Rabat was vital to the crackdown, and that military and colonial administrative goals were in alignment. The railway was similarly key to maintaining British control in the aftermath of this uprising. In a telegram, Marshall opines that the region will ‘remain prosperous and peaceful’ if the Kurdish shaikhs can be tightly controlled – a feat which he argues can be achieved through the construction and maintenance of efficient transport links between their territories and British garrisons.

The railways allowed Iraq’s new imperial authority to respond quickly and with military force to any sign of Iraqi resistance. Further, they underscored that while the old Ottoman order had ended, the British Empire intended to remain in Iraq indefinitely.