Overview

Canons of Mathematical Texts

In the ancient and medieval periods, there was little distinction between mathematical work that was published to disseminate research and that published for pedagogical purposes. Instead, higher mathematics education was based around reading a canon of classical texts, often with the help of commentaries. As the sciences progressed, however, the selection of these canonical texts changed, while their number generally increased.

The ‘Little Astronomy’

The ‘Little Astronomy’ was a label attached to a loose grouping of classical Greek texts of mathematical astronomy that were studied in the Roman Imperial (first century BCE to second century CE) and Late–Ancient periods (third to sixth centuries CE). The canon probably formed slowly over time, and individual teachers probably included or excluded texts according to their own preferences and teaching styles.

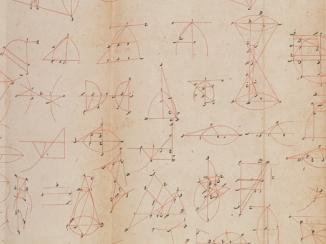

By the Late–Ancient period, this collection was reinterpreted as leading to the study of Ptolemy’s Almagest (mid-second century CE). It was also recognised as containing texts on basic topics in geometry not covered by Euclid’s Elements; the sizes and distances of the sun and moon, Babylonian schemes for rising-times of arcs of the ecliptic, geometrical optics, and spherical geometry – the fundamental mathematics of the ancient and medieval cosmos, and spherical astronomy – a field that dealt with topics such as the length of daylight and night-time, or the rising-times of stars or arcs of the ecliptic.

The Middle Books

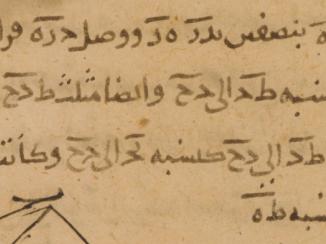

The origin of the collection of works in Arabic known as the Middle Books, or Intermediaries (al-Mutawassiṭāt) is obscure, but it should probably be situated in the activities of scholars around the Bānū Mūsá (ninth century CE) – such as Qusṭā ibn Lūqā (ninth century CE) and Thābit ibn Qurrah (c. 830–901). We are told that Qusṭā wrote a work called Epistle on the Intermediaries Which Must be Read before the Almagest (Risālah fī mā yajibu an yuqraʾa min al-mutawassiṭāt qablu al-Majisṭī), and together, both Qusṭā and Thābit translated and corrected all of the Greek works that were transmitted as the so-called ‘Little Astronomy’. Probably, translations of one or two Greek manuscripts of this collection served as the core of what became the Middle Books.

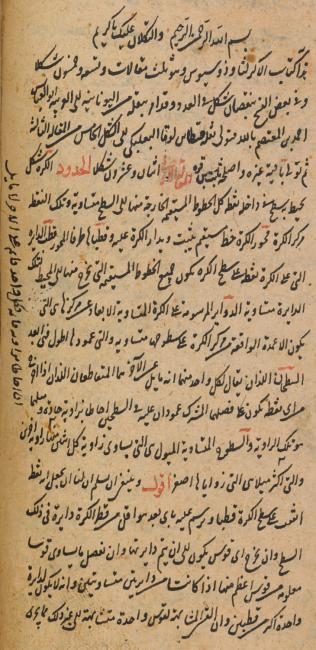

In the medieval period, a number of other treatises were added to the collection – both translations of more advanced Greek treatises, and original Arabic works by the Bānū Mūsá, Thābit and others on geometry and spherical trigonometry. In this more or less settled form, the Middle Books acted as a canon of texts to be studied between Euclid’s Elements and Ptolemy’s Almagest, by those who would master the mathematical sciences. For example, one of Ibn Sīnā’s (980–1037) teachers mentions the Middle Books as one of the works to be studied in a course of the mathematical science of astronomy.

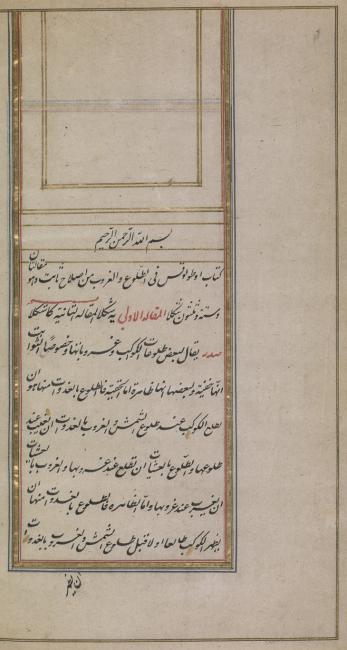

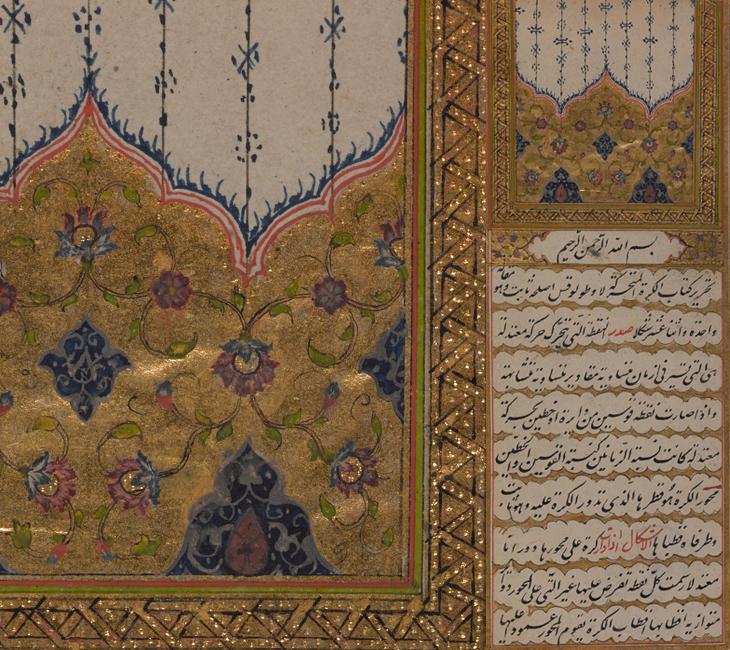

The most widely circulated edition of the Middle Books was the revision by the Persian polymath Nasīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (1201–1274). In the course of re-editing and correcting all of the classic Greek and Arabic texts in the mathematical sciences, al-Ṭūsī also produced revisions of the various treatises of the Middle Books. This circulated in many manuscripts and formed part of the foundation for higher mathematics education in the eastern part of the Islamic world for a number of centuries.

Mathematics Education

In the ancient and medieval periods, higher education was a private affair, based around the teacher-student relationship. Hence, the paths that individuals took in becoming mathematical scholars would have varied considerably. Nevertheless, the fact that some works were regarded as canonical meant that only those who had mastered these texts would be taken seriously as mathematicians. Although there were numerous commentaries and explanatory treatises that were meant to supplement a reading of the classics, higher mathematics education was centred around studying works that had not originally been composed with the student in mind – works such as Euclid’s Elements, the Middle Books, and Ptolemy’s Almagest. This was a text-based education, similar to a literary or a religious education, and the proficient student was that individual who acquired mastery, usually in the form of rote memorization, of the great works of the past masters.